An

Exact

Likeness

The Portraits of John Wesley

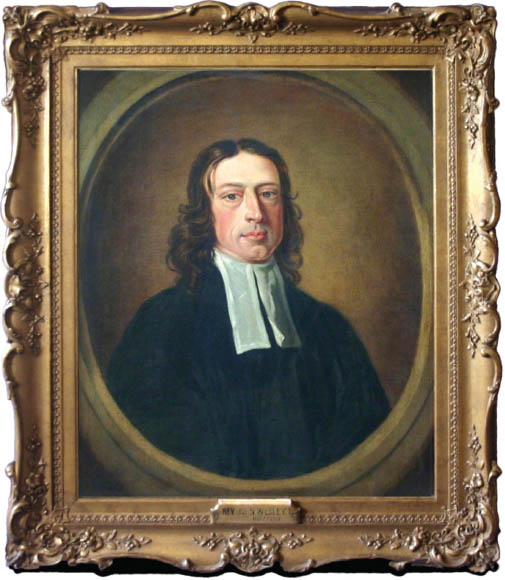

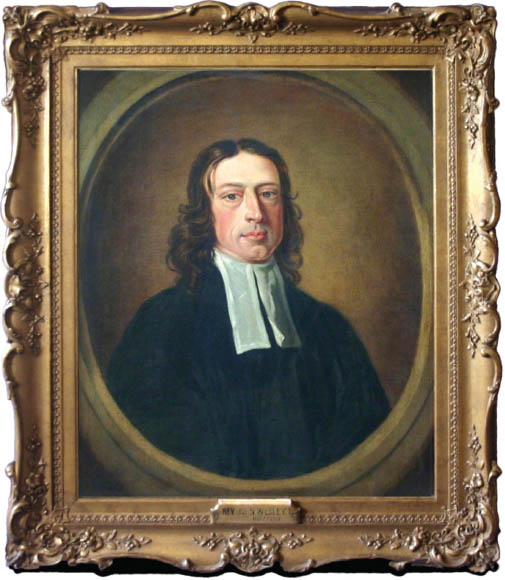

John Wesley, by William Harley (c. 1745) after John Michael Williams, oil painting

An

Exact

Likeness

The Portraits

of John Wesley

Richard P. Heitzenrater

AN EXACT LIKENESS:

PORTRAITS OF JOHN WESLEY

Copyright 2016 by Richard P. Heitzenrater

All rights reserved.

No part of this work may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage or retrieval system, except as may be expressly permitted by the 1976 Copyright Act or in writing from the publisher. Requests for permission can be addressed to Permissions, The United Methodist Publishing House, 2222 Rosa L. Parks Blvd., P.O. Box 280988, Nashville, TN, 37228-0988 or e-mailed to .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data has been requested.

ISBN 978-1-5018-1660-4

16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 2510 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

MANUFACTURED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

To my wife,

Karen

Contents

Introduction

Faces are more than a montage of organs that see, breathe, speak, hear, eat, sing, smell, and yell. As Josephine Tey points out in her mystery novel The Daughter of Time, the slant of an eyebrow, the set of a mouth, the look of the eye, the firmness of a chin, often can provide evidence of character that is as telling as a report card or a police blotter. And those features depicted on portraits of individuals can be equally telling of the persons inner nature or perhaps of what the artist thinks (or wants the viewer to think) about the person being portrayed. Sometimes a portrait might be even more useful than a biography: The real history is written in forms not meant as history.

Portraits are many times viewed as successful or not because of the perception by the public of the persons significance or character, rather than for the value of the portrait as a work of art or the reproduction of the persons photographic likeness. The image portrays something of the persons soul or personality.

The title of this work, An Exact Likeness, appears here in quotation marks for two reasons: (1) Wesley himself used this type of phrase to describe many of the portraits of him that were produced during his lifetime, even though they were unlike his appearance or each other; and (2) there is an irony inherent therein, since the portraits differ greatly and produce no consensus as to his actual likeness.

As for the portraits, Wesleys comments about them were equally blunt at times and evasive at others. He did not completely avoid sitting for artists, though he tended to live out Samuel Johnsons view of him as always being in a hurry. He had little time or money for what he considered frivolities, even though the practice of portrait painting was becoming a more familiar feature of the British scene as the century progressed. And scholars are beginning to see and appreciate this development in the eighteenth century, when portraiture was becoming more common among the non-royal, nongovernmental leaders. Portrait painting became one of the more obvious and perhaps practical implementations of the growing Enlightenment view of the importance of the individual self across the cultural landscape.

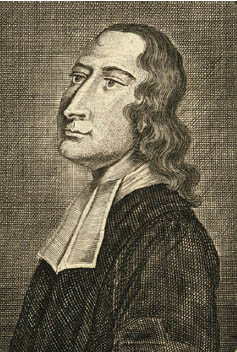

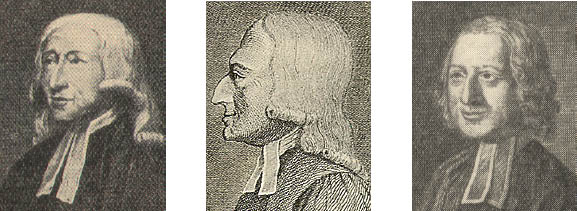

On occasion, my students in the Wesley Studies seminar have been asked to read Josephine Teys detective novel before the course began. Then on the first day, I would give each of them a different photocopy of a portrait, explaining that they were all pictures of eighteenth-century clergymen (see above, engravings of portraits by Worlidge, Hunter, Romney, Hamilton, Nasmyth, and anonymous). They were then asked to describe, as best they could, based on the picture, the character of the person as portrayed in their photocopy.

The descriptions of these clergy by the students were fascinatingly variant, as were the portraits they were examining. Sooner or later, one of the students would guess that perhaps the pictures were all purported to be of Wesley. Nevertheless, the descriptions that they had produced in the meantime were very revealing of their interpretations of the artists intentions and perspectives, perhaps of the intended or hoped-for interpretations by the contemporary viewers, as well as their own interpretive slant on the eighteenth century. The variant portrayals and interpretations of Wesleys portraits often reflect the diverse interpretations of his writings, showing him in both cases to be a very elusive character, to both artists and writers, as well as to viewers and readers.

Contemporary references, including Wesleys own writings, seem to indicate that he allowed at least ten artists to spend time with him in their endeavor to create an artistic likeness: George Vertue, John Williams, John Russell, Nathaniel Hone, Johann Zoffany, Enoch Wood, George Romney, William Hamilton, Thomas Horsley, and Reginald Edward Arnoldseven of them painters. Six of these painters were notable artists of the day, indicated by their membership in the Royal Academy, and some of the others executed their craft well. Wesley seems never to have actually sat for Sir Joshua Reynolds, one of the founders of the Royal Academy, although it is frequently hypothesized that he did.

George Romney

William Hamilton, R.A.

George Vertue

Johann Zoffany, R.A.

Wesley noted that some of the portrait painters took a relatively short time to finish their work, while he seems to cringe at the need of some others for taking more time, which he considered to be very valuable. After sitting for Enoch Wood to create a bust of him in 1781, Wesley began complaining of the amount of time he was wasting, upon which Wood noted that if the sitter would just look up from his book once or twice, it would not take nearly as long. After Wesley acquiesced on this point, he declared that the bust was a bit melancholy in the face. Wood apparently convinced Wesley to sit a bit longer, and after a short bit of reworking, Wesley himself said that Wood should not touch it again or risk damaging a fine piece of work.

Next page