Copyright 1993 by Nicholas Meyer

All rights reserved

First published as a Norton paperback 1995

Use of the Sherlock Holmes characters in this Work

by arrangement with Dame Jean Conan Doyle.

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS HAS CATALOGED THE PRINTED EDITION AS FOLLOWS:

Meyer, Nicholas.

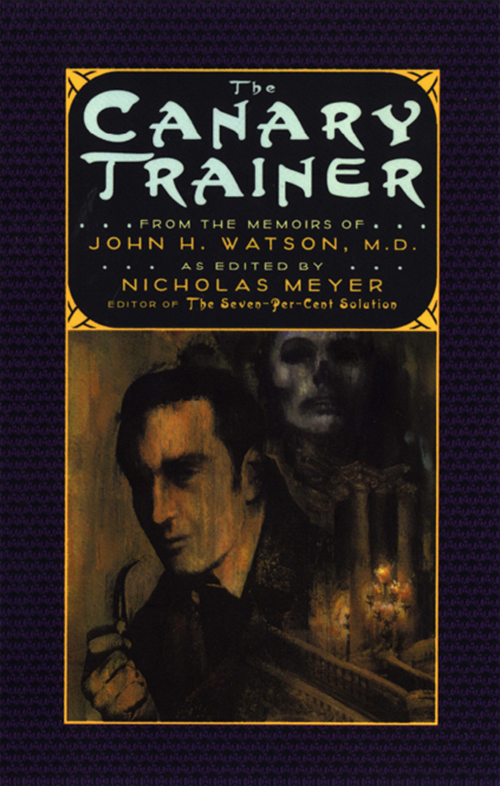

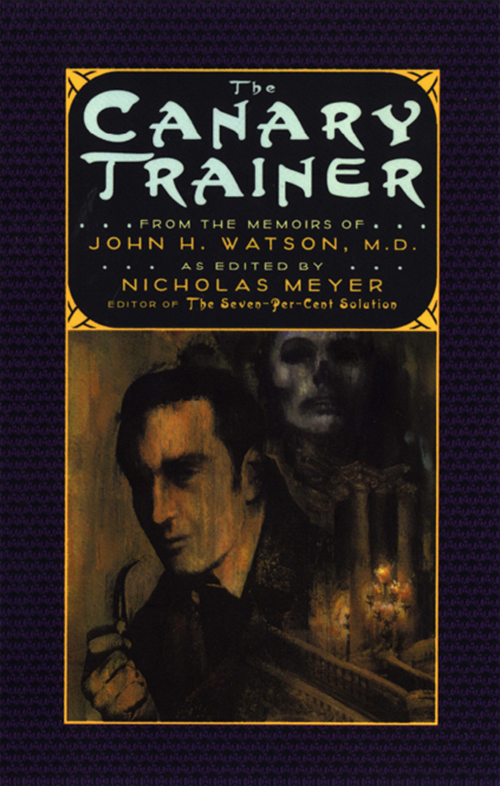

The canary trainer: from the memoirs of John H. Watson, M.D. / as

edited by Nicholas Meyer

p. cm.

Sequel to: The seven-per-cent solution.

1. Holmes, Sherlock (Fictitious character)Fiction. 2. Private

investigatorsFranceParisFiction. 3. OperaFranceParis

Fiction. 4. Paris (France)Fiction. I. Title.

PS3563.E88C3 1993

813.54dc20

9313149

ISBN 13: 978-0-393-31241-6

ISBN 978-0-393-24856-2 (e-book)

W. W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

W. W. Norton & Company Ltd., Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT

for Lauren, for Rachel, and for Madeline

with all the love there is

L ocated by a computer in the bowels of a major university, this missing manuscript by Dr. John Watson, the biographer of Sherlock Holmes, reveals for the first time a hitherto unknown episode in the life of the Great Detective.

The year is 1891, Paris is the capital of the western world, and its opera house is full of surprises. First and by no means least is the sudden reappearance of the great love of Holmess life, an accomplished singer from Hoboken, New Jersey. Second is the series of seemingly bizarre accidents each more sinister than the lastallegedly arranged by the Opera Ghost, an opponent who goes by many names and is more than equal to Holmes. Alone in a strange and spectacular city, with none of his normal resources, Holmes is commissioned to protect a vulnerable young soprano, whose beautiful voice obsesses a creature no one believes is real, but whose jealousy is lethal.

In this dazzling, long-awaited sequel to The Seven-Per-Cent Solution, the detective pits wits against a musical maniac, and we are treated to an adventure unlike any other in the archives of Sherlock Holmes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

U sually, at the conclusion of these pastiches, I am at pains to express my gratitude and admiration first and foremost for the happy genius of Arthur Conan Doyle, whose creation has brought so much pleasure to so many.

On this occasion, my thanks to Doyle must also be accompanied by an equal debt of gratitude to the man who wrote The Phantom of the Opera. Why Gaston Lerouxs fantastic, absurdist masterpiece should be so neglected is quite beyond mepossibly the various movie and pop-opera versions have preempted publishers perceptions of its value, which is wrongbut in exchange for borrowing it and improvising my own variations upon it, I felt it fitting to make Leroux the orchestra conductor, who could truthfully say that he was responsible for everything, that the smallest detail did not escape his attention. Leroux was apparently a big Sherlock Holmes fan, so it is only fitting that they got to meet.

One confession: Leroux states that the events he is about to describe occurred not more than thirty years ago. Since his novel was published in 1911, that could mean 1881, a date not compatible with the Holmesian chronology. I therefore have given a loose interpretation to the words not more than and brought the action of the Ghost forward by ten years. I hope no one is too bent out of shape by this.

In addition, I am, typically, indebted to a host of Sherlockian scholars and theoreticians, chief among them the late William S. Baring-Gould, author of the first Holmes biography as well as annotator of the Clarkson N. Potter complete edition, whose chronology I have accepted without demur.

Two Holmesian reference works proved invaluable, Sherlock Holmes and Dr. John H. Watson, M.D.: An Encyclopedia of Their Affairs, by Orlando Clark; and The Encyclopedia Sherlockiana: A Universal Dictionary of Sherlock Holmes and His Biographer, John H. Watson, M.D., by Jack Tracy.

I am also indebted to Otto Friedrichs chatty history of the Second Empire, Olympia: Paris in the Age of Manet, which fueled my interest in things nineteenth-century and French long before I dreamed of writing this book, as well as the Guide Michelin for Paris, which came in very handy after I had made the decision.

I owe particular thanks to my wife, Lauren, whose patience, advice, encouragement, editorial acumen, and unflagging enthusiasm kept me going when I became confused.

There is one final contributor who must be acknowledged.

So your old mans a shrink, they said to me throughout my childhood. Is he a Freudian?

How was I supposed to know?

Hey, Pop, are you a Freudian?

Its a silly question, he answered, lighting his pipe.

How come?

Because you can no more discuss the history of psychoanalysis without starting with Freud than you can discuss the history of North America without beginning with the Indiansor Columbus. But to suppose that nothing has happened since Columbus is not only absurd, it is wildly incorrect. And it would be equally rigid and terribly doctrinaire to act as if nothing had happened since Freud.

(He then went on to present his mapmaking analogy with Columbus, which appears in the beginning of this novel.)

When a patient comes to see me, my father continued, I listen to what he says. I listen to how he says it. I try to hear what he does not say. Against these and other points of observation I apply a background of some clinical experience. I am, in short, searching for cluesfrom himto help me determine why he is not happy. Freud doesnt much enter into it.

There was a long pause as I digested this. I watched my father puffing contentedly on his pipe. Suddenly I knew who it was that Sherlock Holmes had always reminded me of, all this time. I just hadnt been able to put my finger on it.

Thanks, Papa.

EDITORS FOREWORD

Beinecke Library

Department of Special Collections

Yale University

New Haven, Connecticut

December 11, 1992

Dear Mr. Meyer:

I am assistant curator for Special Collections at the Beinecke, and I am writing to ask your advice and also your assistance.

As you may know, the Beinecke is the recipient of an enormous number of valuable papers and manuscripts from donors the world over.

Recently we have transferred our entire catalogue from an analog to a digitalized computer format in order to facilitate referencing, a process that has consumed several months (and two million dollars). Along the way, we have unearthed several documents which were not properly identified or studied at the time of their acquisition.

Among the papers on repository at the library are several pertaining to the estate of Martha Hudson, whose brother-in-law, Gerald Forrester, was a distinguished Yale alumnus (03). The university has been in possession of these papers for over fifty years.

I am ashamed to confess that the name Martha Hudson did not mean anything to my predecessor and so, l fear, her papers escaped the scrutiny they deserved. It was only when the digital catalogue transfer occurred that we realized that this Martha Hudson was for thirty years the housekeeper of Sherlock Holmes.

Next page