The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To the lifers

The judge sentenced me to this institution, but Ive chosen to follow the Quaker path and live in the penitentiary.

Teddy

We have brothers who struggle because theyre still carrying the dead man on their back. Back when we came into the love of God and the relationship grows, the things God doesnt like are dismissed. Thats how we dont do the things that we used to do.

Al

The Creator made the world and said: Have at it , fellas.

Baraka

CONTENTS

PREFACE

THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 16, 2006

Baraka warned me against talking to Al about such things. And yet, only weeks later, I arrive in the office to find the two old friends warring over Gods Word and how we come to know it. Als enormous frame is hunched behind his desk, disquietingly still. Baraka sits opposite him, riding the desk still referred to as Sayyids, though by now everyone pretty much accepts that Sayyid isnt coming back. Teddy is reclining in his desk chair by the window, exuding impishness. I grab an empty seat and catch myself up.

In Als perspective, because God is a loving God, He wants to be understood and so grants man unmediated access to His Word. For Baraka, by contrast, Gods mind is knowable only via a tenuous chain of custody, one that stretches from the prophets, to the scribes, to the compilers who endowed certain accounts with the seal of authority. For Baraka, then, placing faith in Scripture means trusting other men. For Al, faith requires circumventing mans machinations and trusting only in God.

To find Baraka and Al at opposite ends of a religious dispute should come as little surprise, but not simply because Baraka is a Muslim and Al is a Christian. In the chapel, as it turns out, such boundaries are far less decisive than I had initially assumed. Rather, if this mornings clash reveals a chasm between the two men, it is less a matter of creed than of temperament. Baraka is intellectually playful, a lover of ideas and debate, and a great believer in the power of the mind. Nothing riles Baraka like genuflection before orthodoxy, whatever its standard. As one of the politically minded graybeards who came of age in the Nation of Islam before the movement collectively converted to Sunni Islam in 1975, Baraka sees in the Quran and the Bible not so much rigid formulae for serving God as catalogs of time-tested strategies for individual and collective improvement. Its an approach that, in Als judgment, cant possibly yield anything good. For Al, because the human is rotten to the core, the intellect can only lead him astray. Through Gods abundant love, however, the Holy Spirit delivers the truth of the Word directly to the believers heart and elevates him to a moral plateau he couldnt possibly achieve on his own. Mulish in his convictions, and not only in matters of ultimate concern, Al is alternatively capable of unnerving fury and disarming lovea fury that hints at the monster Al says he used to be, and a love Im tempted to call Christian, though Al would not, since if Jesus wanted His followers to call themselves Christians, He would have told them so himself.

Baraka holds up a softbound New Testament that he must have pulled off the bookshelf. Who put this book together? he asks Al.

Man did! Teddy barks. I know, because my sister works in a bookshop!

The Holy Ghost, Al says, accustomed to tuning out the noise.

And what about the Council of Nicaea? Baraka asks. What about the process of canonization?

Thats what they did, Al says. The they here is the Roman Catholic Churcha manmade entity, which, for Al, has little overlap with the transhistorical band of Jesus true followers he calls the body of Christ.

But didnt they put it together? Baraka presses.

No, not the body of Christ.

Baraka elevates an eyebrow. Then where do you get this information from? He points to the Bible.

The Holy Ghost, Al says, still unmoved.

Never one to feign understanding, Baraka doesnt get it now, either. So let me get this straight. You recite stuff thats in their book, but

Al cuts him off. Thats them . I know what the Holy Ghost said.

And how do you know?

I know because of the Holy Spirit.

With prosecutorial coyness, Baraka cocks his head to the side. And yet you read the exact same book.

Look. Im not part of that there. Thats the birth of something else.

But you recite verbatim what they wrote!

Its not about what they wrote . Its inspiration.

Baraka tries a different tack. And what about the books that didnt make it into the canon. They real?

No.

And how do you know?

Because the Holy Spirit shows it to me.

The Holy Spirit shows you the whole truth?

Yes. The whole truth of the Word.

Teddy sits up, suddenly earnest. Look, he explains. We dont know everything about God. But we know what the sixty-six books say.

But youve got it all in English! Baraka objects.

I dont know what language He talks to you in, Al snaps.

Springing himself off Sayyids desk, Baraka crosses the cramped room in two steps, flips open the Bible, turns it over, and places it in front of Al. He points to a line. What does that say?

Al reads from what I will later determine to be Isaiahs vision of Zions destruction: Your country lies desolate, your cities are burned with fire; in your very presence aliens devour your land; it is desolate, as overthrown by foreigners .

Thank you, Baraka says. He snatches back the Bible and crisply returns to Sayyids desk. Now, what language is that ?

Staring down his old friend, Al answers a different question. But why does the country lie desolate? Because of mans disobedience. That is to say, I take it, because of arrogant inquiries of precisely this sort. At which point, feeling that Als indictment is directed as much at me as at Baraka, I break my silence and jump in.

* * *

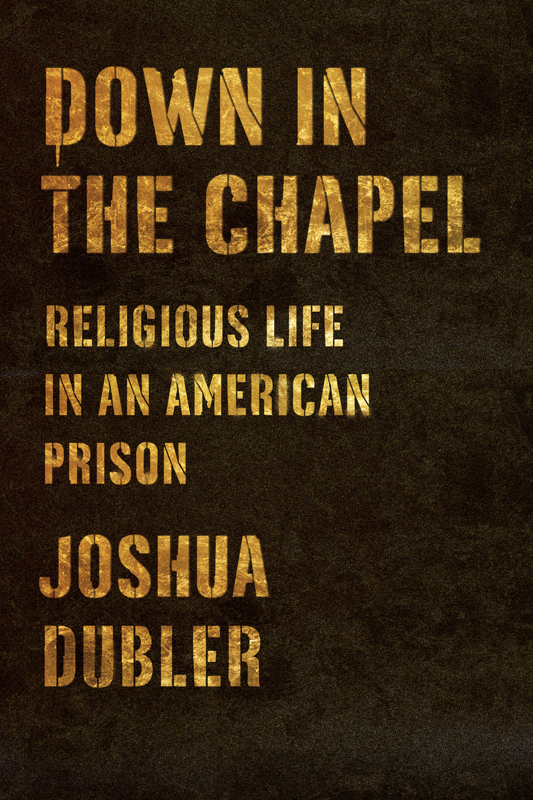

Baraka, Al, and Teddythese are not their real names, but over time they have come to suit them fine. Each works in the chapel at Pennsylvanias Graterford Prison: Baraka as a clerk, Al as an audio-video technician and Teddy as a janitor. Baraka is a Muslim, and Al and Teddy are Christians. Each grew up in South Philadelphia, and each was convicted of homicide. Baraka and Al are in their early fifties, while Teddy is a decade their junior. Teddy has been at Graterford since the nineties, Al since the eighties, and Baraka since the seventies. As is true of roughly two-thirds of Graterfords 3,500 residents, all three men are black. Barring a change in the law, a revision to administrative procedure, or a legal miracle, all three will die in prison. As for me, Im far more transient. By now more or less a secular Jew, Ive been in the chapel for a year, researching my dissertationresearch that, in time, will grow into this book.

This book tells the story of one weeks time in Graterfords chapel. It recounts seven days during which two prison guards, five chaplains, fifteen prisoner workers, a score of outside volunteers, and hundreds of religious adherents frequent the chapel to work, pray, study, and play. Driven by characters in conversation, this book offers a mosaic of the ritual and banter through which the men at Graterford pass their time, care for their selves, foster relationships, and commune with their makers, among a variety of other activities earnest and absurdist, quotidian and momentous. Inescapably, it is also the story of what happens when an interloper, in the form of a visiting scholar of religion, is thrown into this mix with the hope of making sense of it all. As such, while this book is an exploration of doing time and doing religion in contemporary America, it is simultaneously a chronicle of the tangled process by which one comes to know things through dialogue with other people.