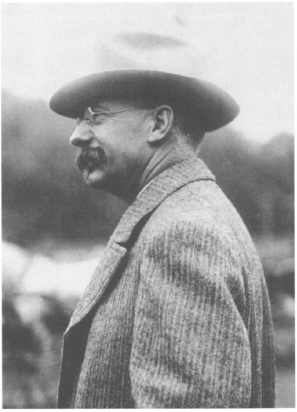

The life & legend of E. H. Harriman

by Keystone Typesetting, Inc.

Council on Library Resources.

The life and legend of E. H. Harriman / Maury Klein,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-8078-6553-2 (cloth: alk. paper)

1. Harriman, Edward Henry, 1848-1909. 2. Capitalists and financiersUnited StatesBiography. 3. Railroads United StatesHistory. I. Title.

Acknowledgments

The research and writing of this book owe much to people in many capacities who contributed freely of their time and energy. Although it would be impossible to name them all, the following individuals stand out for their efforts and cooperation. Donald D. Snoddy of the Union Pacific Museum was a rock on whom any researcher could lean for support. In this project, as in previous ones, he provided a full measure of help and good cheer. Ken Longe of the Union Pacifics public relations staff also responded to every request with alacrity. I am especially grateful to Jim Ady of Salt Lake City, who brought to my attention certain invaluable records of the Los Angeles & Salt Lake Railroad that he had personally saved from destruction.

William J. Rich III helped me gain access to the materials stored at Arden Farms, which turned out to be a mine of useful information. At Arden Farms, George Paffenbarger generously gave me complete access to the Kennan and other materials, office support, and useful advice. Frank Allston of IC Industries granted me access to the early minute books and records of the Illinois Central Railroad still in possession of IC Industries.

Librarians in several locations provided their expertise as well as access to key collections of papers. Foremost among them were Florence Lathrop of Baker Library at the Harvard Business School, W. Thomas White of the James J. Hill Reference Library in St. Paul, John Aubrey of the Newberry Library in Chicago, Mary Ann Jensen and Andy Thomson of the Firestone Library at Princeton University, Andrea Paul of the Nebraska State Museum and Archives, Bernard J. Crystal of the Butler Library at Columbia University, Richard Crawford of the National Archives, and Margaret N. Haines of the Oregon Historical Society.

The staff of my home library at the University of Rhode Island fielded my every request with their usual efficiency and helpfulness. In particular I wish to thank Marie Beaumont, Vicki Burnett, John Etchingham, Mimi Keefe, Sylvia C. Krausse, Kevin Logan, John Osterhout, and Marie Rudd. Several friends and colleagues were generous with their advice and support on various subjects. Their ranks include William D. Burt, Don L. Hofsommer, Priscilla Long, Albro Martin, Lloyd J. Mercer, and Glenn Porter. Frank A. Vanderlip Jr. helped me understand his banker father. I benefited, too, from interviews with Elbridge T. Gerry, W. Averell Harriman, and Robert A. Lovett in my earlier Union Pacific project.

My editor, Lewis Bateman, has been uniformly helpful, as have Pamela Upton and other members of the staff at the University of North Carolina Press. Trudie Calverts fine copyediting rescued me from numerous bloopers.

Finally, I wish to pay tribute to my wife, Kathy Klein, who endured with patience and understanding the perpetually vacant expression of the writer lost in thought.

Introduction

At this end of the twentieth century the name of E. H. Harriman may be less familiar than that of his son W. Averell Harriman, who followed an already impressive career in business with long and distinguished service in diplomacy and politics. To any American living in the first years of this century, however, the name and face of E. H. Harriman were as familiar as those of his fellow titans J. P. Morgan, John D. Rockefeller, and Andrew Carnegie. Like them, he had become to the public the very essence of what he did. Morgan stood for banking, Rockefeller for oil, Carnegie for iron and steel, and Harriman for railroads. But where the first three men had achieved their lofty reputations through a lifetime of steady achievement in their fields, Harriman burst onto the railroad scene like a comet at the age of fifty and worked his magic on the industry in a single decade.

Harriman differed from the others in personality as well. Morgan was aloof and aristocratic, Rockefeller secretive and reclusive, and Carnegie voluble and hungry for the limelight. Harriman was intense and combativethe forerunner of an age when speed and efficiency would replace grace and charm. On duty he was a human computer, his mind racing so quickly over data to conclusions that others could hardly follow him. Coming late to railroads, the oldest and most hidebound of major industries, he looked at its hoary traditions with fresh eyes and with startling speed literally reinvented the business. In one decade his innovations shoved an industry made moribund and dispirited by the depression of 1893-97 into the twentieth century. The railroads under his control became models for others to emulate. He modernized not only their physical plant but their organizations, business practices, financing, and safety records.

He began in 1898 with the Union Pacific Railroad, the once-proud transcontinental line then emerging in pieces from nearly five years of bankruptcy. In only a few years Harriman rebuilt the line, reorganized its management, reacquired its lost subsidiaries, and turned it into one of the most profitable properties in the nation. In 1901 he acquired the Southern Pacific, then the largest transportation system in the world, and worked the same formula on it. To the newly integrated Union Pacific-Southern Pacific system he brought a bold management structure that shocked traditional railroad men because it seemed to violate all the known principles of how such things were done. The Harriman touch was extended to other roads and with it the formula that became the mantra for railroad success in the twentieth century: long hauls of high volume at low rates. Harriman did not invent the formula, but he applied it more rigorously and with greater speed and efficiency than anyone else.

Harrimans vision did not stop at the waters edge or the national boundary. He built lines into Mexico and looked to extend them deep into Central America. Late in life he envisioned a combined rail-water transportation system that would circle the globe. To that end he visited Japan and negotiated for rights to construct lines in China, Manchuria, and elsewhere that would complete such a system. Nothing stirred him more than a challenge. In 1899 he transformed a vacation cruise to Alaska into a major scientific expedition that left a lasting legacy of knowledge about the region. When the earthquake of 1906 devastated San Francisco, Harriman rushed to the scene to direct Southern Pacific operations personally. When the Colorado River overflowed its banks and threatened to immerse the entire Imperial Valley of California, he ordered the Southern Pacifics long and expensive campaign to force the river back into its bed.