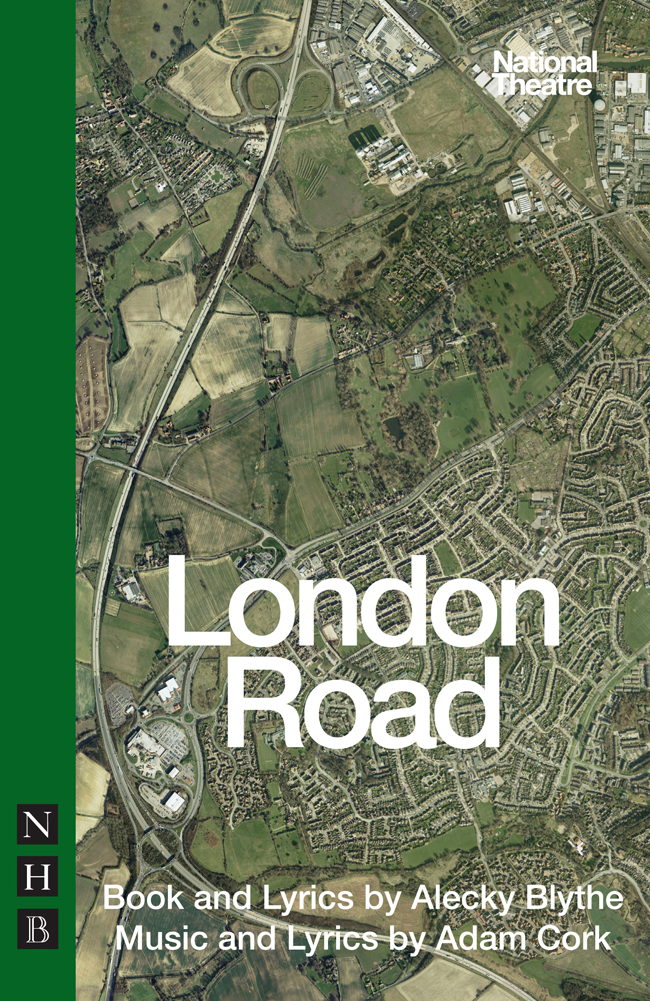

LONDON ROAD

Book and Lyrics by

Alecky Blythe

Music and Lyrics by

Adam Cork

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

Singing for Real

Development of the project

In the spring of 2007 I was invited to take part in the writers and composers week at the National Theatre Studio. The purpose of the week was to pair up a handful of writers and composers, put the pairings in a room together and see if any interesting discoveries were made by the end of it. The wonderful thing about the Studio is that on the surface it gives artists the opportunity to experiment and get things wrong. However, underneath this relaxed, cosy veneer, those who are lucky enough to workshop projects there know that in some cases there is the slim but real potential for them to be brought to life on the South Bank. So it was in an atmosphere of latent dreams that Adam and I first met.

I was delighted to be at the workshop, as working with music was a voyage into uncharted territory for me. As my work is made from recorded everyday conversations and replicated by actors as authentically as possible, musical theatre, with its necessary affectation, is not a genre that sits easily with me. I wanted to find out if I could adapt the verbatim technique in a way which incorporated music without losing its honesty.

Development of the technique

I work using a technique originally created by Anna Deavere Smith. Deavere Smith was the first to combine the journalistic technique of interviewing her subjects with the art of reproducing their words accurately in performance. It was passed on to me via Mark Wing-Davey in his workshop Drama Without Paper.

The technique involves going into a community of some sort and recording conversations with people, which are then edited to become the script of the play. However, the actors do not see the text. The edited recordings are played live to the actors through earphones during the rehearsal process, and onstage in performance. The actors listen to the audio and repeat what they hear. They copy not just the words but exactly the way in which they were first spoken. Every cough, stutter and hesitation is reproduced. Up till now for my previous shows, the actors have not learnt the lines at any point. By listening to the audio during performances the actors are helped to remain accurate to the original recordings, rather than slipping into their own patterns of speech or embellishment.

The considerable musical dimension of London Road has required a rethinking of the presentation of this recorded-delivery verbatim technique. By setting some of the material to music even though Adam has been scrupulous in notating the tune of the spoken voice so that it remains faithful to how it was first said the fact that at times characters sing their words instead of speak them as they did in real life, is a departure from the purer verbatim form of my past endeavours. In keeping with the songs being learnt from the score, the spoken text has also been learnt. With both the songs and the spoken text the audio has remained intrinsic to the process, so that the original delivery as well as the words are learnt.

I had arrived at the writers and composers week armed with a range of material with which we could experiment but it was the interviews that I recorded in the winter of 2006 in Ipswich that best lent themselves to musical intervention. What Adam and I discovered with the music was that it succeeded in binding together shared sentiments that were being echoed throughout the town during those worrying times. More importantly, Adam was able to set these words to music by following the cadence and rhythms of the original speech patterns so accurately that it did not diminish their verisimilitude. I was also excited to have a new tool at my disposal with the songwriting. By creating verses and choruses, I could shape the material for narrative and dramatic effect further than I had ever been able to do before. To my surprise, we had between us the seeds of both the subject and the technique to take to another stage.

Development of the story

My first interviews from Ipswich were collected on 15th December 2006; five bodies had been found but no arrests had been made. The town was at the height of its fear. I had been gripped and appalled by the spiralling tragedies that were unravelling in Ipswich during that dark time. It would of course be a shocking experience for any community, but the fact that it took place in this otherwise peaceful rural town, never before associated with high levels of crime or soliciting, made it all the more upsetting for the people who lived there. It was not what was mainly being reported in the media about the victims or the possible suspects that drew me to Ipswich, but the ripples it created in the wider community in the lives of those on the periphery. Events of this proportion take hold in all sorts of areas outside the lead story, and that is what I wanted to explore.

It was not until six months later, when I returned to Ipswich to gauge the temperature of the town after the arrests but before the trial, that I stumbled upon what was to me the most interesting development so far. A Neighbourhood Watch that had been set up at the time of the murders had organised a London Road in Bloom competition and the street could not have looked more different from when it had been besieged by the media the winter before. Hanging baskets lined the roads and front gardens were bursting with floral displays. Such was the impact of the terrible happenings in that area that the community had come together and set up a series of events, from gardening competitions to quiz nights, in order to try to heal itself. Although this had some coverage in the local press, the national media had not reported this final and important chapter of the story. Over the course of the next two years, I regularly revisited the residents of London Road to chart their full recovery.

I would like to say a special thank you to everyone who shared their stories with me, particularly the members of the London Road Neighbourhood Watch, without whose generosity the play would not have been possible.

Alecky Blythe, 2011

Saying in Tune

When I first met Alecky at the National Theatre Studio almost four years ago, as part of an experimental week which brought together composers and playwrights, I had no idea that Id be working with a verbatim practitioner. And when Alecky explained the concept and methods of this documentary form to me, I have to admit my very first thought was How on earth can I turn this into music? But when we started listening to her interviews, I began to feel that this could be an inspiring new approach to songwriting, or, more accurately, an exciting development of an existing way of composing songs. Whenever Ive set conventional texts to music, Ive always spoken the words to myself, and transcribed the rhythms and the melodic rise and fall of my own voice, to try and arrive at the most truthful and direct expression of the text. And here was an opportunity to refine that to a much purer process, without any authorial or poetic interpretation (not to mention my own bad acting) polluting the connection between the actual subject and his or her representation in music.

And so we began, with a few ideas about what we wanted the piece to be. My initial aim was that the music should be as articulated as possible, otherwise we wouldnt be doing justice to the reality and the uniqueness of the depicted people. I also wanted to seize the challenge of taking an experimental idea and developing it into something which could be interesting as both music and drama. I didnt want to reference any overall musical style, but rather, discover responses suggested by the material on a moment-by-moment basis. For that reason I didnt foresee much cross-pollination of musical motifs from one song to another, although I did want the identity of each individual song to be clear; I felt this was the only way I could create musical meaning from this un-versified, spontaneously spoken text. I also hoped that, in the spirit of the documentary concept, the musical score would be like a time capsule inside which the speech rhythms would be captured and contained, frozen and fossilised in music just as they have a fixed existence on Aleckys recordings. And I wanted to find a way of singing with the quality of speech, which is altogether different from either an operatic or a conventional musical-theatre vocal style. In this last wish I have been very lucky, as our Musical Director David Shrubsole and the voice expert Mary Hammond have together helped the cast develop and maintain a speech-like way of singing which engages their prodigious techniques from a variety of disciplines.