MUDDLING THROUGH

THE REMARKABLE STORY OF THE BARR COLONISTS

LYNNE BOWEN

Copyright 1992 by Lynne Bowen

94 95 96 97 98 5 4 3 2 1

First paperback edition 1994

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any means without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review.

Greystone Books

A division of Douglas & Mclntyre Ltd.

1615 Venables Street

Vancouver, British Columbia V5L 2H1

Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data

Bowen, Lynne, 1940

Muddling through

Greystone Books

ISBN 1-55054-105-6

1. Barr Colony (Alta. and Sask.) 2. BritishPrairie Provinces History20th century. 3. Agricultural coloniesPrairie Provinces History20th century. 4. Prairie ProvincesEmigration and immigrationHistory20th century. 5. Prairie Provinces ColonizationHistory20th century. 6. Great BritainEmigration and immigrationHistory20th century. 7. ImmigrantsPrairie ProvincesHistory-20th century. I. Title.

FC3242.9 B37B69 1994 971.242 C94-910044-7

F1060.9.B69 1994

Editing by Barbara Pulling

Design by The Typeworks

Cover design by Eric Ansley and Associates Ltd.

Cover photographs courtesy Provincial Archives of Alberta/A9391 and

collection of the author

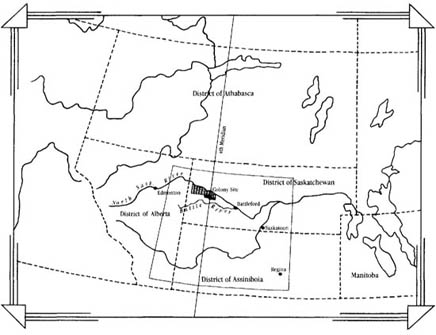

Maps by Andrew Bowen

Printed and bound in Canada by D. W. Friesen & Sons Ltd.

Printed on acid-free paper

The author wishes to acknowledge the generous support of the Canada Council.

To the memory of

Isobel Willis Boyd Crossley

1912-1989

Preface

THE TELLING OF HISTORY IS THE TELLING OF STORIES. WHETHER THE STORIES are told around a campfire, confided to a diary or written in a memoir or government report, the history of all people on earth is told in stories.

I grew up on the stories of the Barr Colonythe gentle tales told to me by my grandmother and the lively and sometimes outrageous ones told by my grandfather. Grandpa had a way with an audiencehe was a good storyteller. In the years since he died, I have come to realize that good storytellers exaggerate, embellish, borrow and even lie. But the embellishments hold the audience, making the story more real for each listener, and I believe that as long as essential truths are told and no one is slandered, more good than harm is done by a good storyteller.

Many storytellers contributed to this book. I have used their stories to tell, as accurately as I can, how over two thousand British clerks, butchers, housewives, ex-Boer War soldiers, saleswomen and remittance men followed a charismatic but inept Anglican minister to the Canadian prairies. Some told their stories to their diaries, probably the best source of raw material. Others wrote letters to parents and fiancees, distorting the truth a little or a lot to spare the recipient. Those who wrote books had more time to consider, and more time to bend and stretch the facts. Government documents told stories too, stories stripped of artistry if not of artifice.

As the writer of two books of coal mining history, I have had to explain on many occasions that it was not necessary to be a coal miners daughter to tell the miners story. But it would have been nice to have been able to answer yes when asked that question. For this book, I can say, Yes. I am a Barr colonists granddaughter, and a grandniece, and a second-cousin-by-marriage-twice-removed.

To track down the stories of my family and of many other families, I returned to the prairies several times to work with the Barr Colony collections in a number of prairie archives. There were Barr Colony descendants and even two survivors to meet. I wanted to see Barr Colony country and refresh my memory of the prairie landscape.

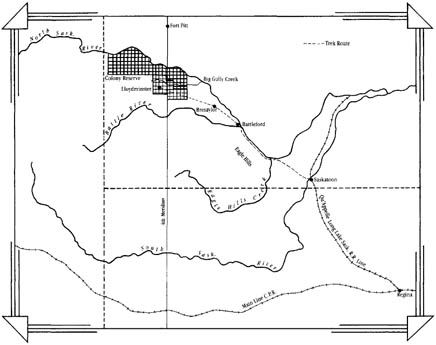

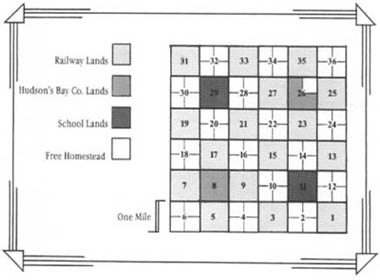

Even prairie dust can be evocative when one is discovering ones roots. My favourite trip was the one during which my husband and I retraced the trek, flirting with the actual route as we followed back-roads, encountering trail-blocking fences and stumbling onto recognizable landmarks. I met Barr Colony relatives for the first time, learned how to read a township map, drank the hard water and realized that my twenty years spent on the lush British Columbia coast had only enhanced my appreciation for the subtler beauty of the prairies.

My cousin Mildred was seventy-nine when we visited in the spring of 1990. She asked us to drive her into town to pick up her airplane, which she flew back to the landing strip on her farm. That landing strip runs along a large slough. On the other side of the water is a precious legacy that Mildred has preservedland that has never been ploughed, virgin prairie. We felt the springiness of the dead grasses, heard the crunch of prairie wool under our feet and felt closer to the people who walked on it ninety years before us. Mildred took us to the site of the family homestead; she scrambled across a muddy ditch and up a small knoll to show us where the sod house used to stand. The land and the sky dwarfed her. When Mildreds father was nineteen, a former clerk in a commercial travellers office, he took this land on and made it work for him.

My own father died before I began this project, but he left me with a few of his fathers treasuresa plough handle, a letter from Isaac Barr and a bill of sale for a pair of oxen. Muddling Through is dedicated to my mother. She transcribed the interviews for this book, but she died while I was writing it. I miss her very much.

Not all the descendants of Barr colonists will find their ancestors names mentioned in this book, but the story belongs to all of themthe children and grandchildren to the fourth and fifth generations. To those generations of my family: Here are some of the stories that made you what you are. And to my grandfather: Thank you for the storiesfor the ones that happened just as you told them, for the ones you borrowed from others and for the ones that got better and better as the years went by.

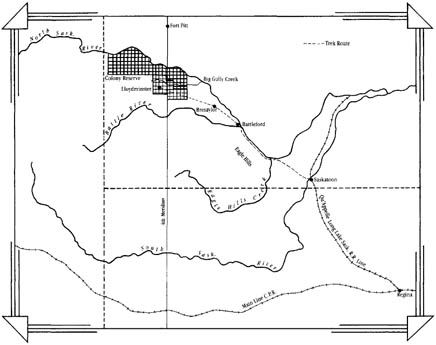

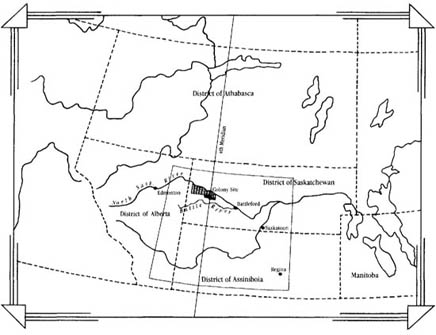

North West Territories, 1903

The Promised Land, 1903

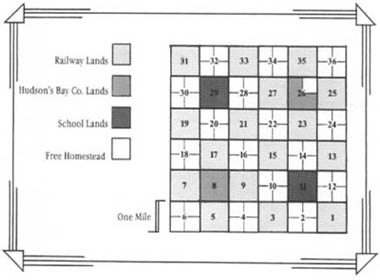

A Typical Prairie Township

The English race gets continually into the most unheard of scrapes all over the world by reason of its insular prejudices and superiority to advice; but somehow they muddle through and when they do they are on the ground to hold it.

Manitoba Free Press, December 1903

Prologue

IN THE LAST DAYS OF MAY IN THE YEAR 1903, NOAHS ARK CAME TO REST ON THE mud bottom of a large slough thirty miles from the Promised Land. The remnants of a late spring snowfall lay in patches on the low surrounding hills, blackened by a recent prairie fire. The wind blew, raw and penetrating.

Noahs Ark was not a boat. Spoked wheels, just visible above the surface of the water, gave away its true identity. It was a high and utilitarian Bain wagon topped with a peaked roof of wood and tarpaper. The master of this strange craft was Thomas Edwards. It was whispered around that Edwards was demented and that the Ark was proof of it.