Title Page

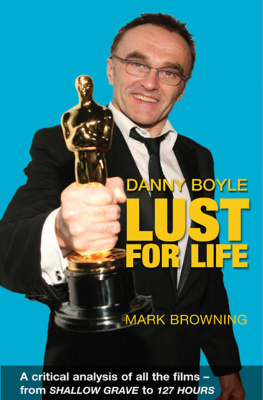

DANNY BOYLE

LUST FOR LIFE

Mark Browning

Publisher Information

First published in 2011 by

Chaplin Books

1 Eliza Place

Gosport PO12 4UN

Tel: 023 9252 9020

www.chaplinbooks.co.uk

Digital edition converted and distributed in 2012 by

Andrews UK Limited

www.andrewsuk.com

Copyright Mark Browning

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in any retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the copyright holder for which application should be addressed in the first instance to the publishers. No liability shall be attached to the author, the copyright holder or the publishers for loss or damage of any nature suffered as a result of reliance on the reproduction of any of the contents of this publication or any errors or omissions in its contents.

Design by Helen Taylor

Introduction

I want people to leave the cinema feeling that somethings been confirmed for them about life

(Danny Boyle)

The genesis for this book was the moment Danny Boyle came bouncing, in his words in the manner of Tigger, onto the stage to collect his Oscar for Best Director in 2009. Slumdog Millionaire had been in competition with David Finchers The Curious Case of Benjamin Button in a number of categories, and proceeded to win every single one. On the one hand, Finchers movie had a $150 million budget, state-of-the-art special effects, and a cast headed by Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett; on the other, Boyles movie had only $20 million behind it, no special effects to speak of, dialogue that was partly in Hindi and a cast of minor actors and non-professionals. In fact, before Fox Searchlight picked up the film for a theatrical release, it was destined to go straight to DVD. Could Fincher, a perfectionist famous for demanding extended re-shoots and with a highly technical approach to filmmaking, have even been capable of making Slumdog Millionaire ? It would be hard to imagine a greater juxtaposition of styles and it made me think about Boyles career and how he had reached that point.

Boyle was born on 20 October 1956 into a working-class family (his mother a hairdresser and dinner lady; his father a farm labourer) and was imbued with a strong work ethic from an early age, underlined by an all-encompassing sense of Catholic sin and redemption. He had a place at a seminary in Upholland in Wigan until persuaded by a priest, Father Conway, that perhaps this was not his true vocation, and instead went to Bangor University to study English and Drama.

His career began in the theatre, as an usher for the Joint Stock Theatre Company, known for their cutting-edge productions, and eventually as a director. In 1982 was appointed artistic director at the Royal Court Theatre Upstairs, where he was responsible for a number of small-scale productions including Howard Brentons The Genius and Edward Bonds Saved, the latter winning a Time Out award. In 1985, he graduated to the main stage, directing several further successful projects, including The Last Days of Don Juan for the Royal Shakespeare Company.

When he moved into television, he went first to the BBC in Northern Ireland to produce the powerful drama Elephant (Alan Clarke, 1989) about the sectarian killings, before moving back to the mainland to direct an historical drama about a religious sect, Mr Wroes Virgins (1993), and two early episodes of Inspector Morse , one on Masonic ritual and one on rave culture. While his work on Morse shows little obvious cinematic flair, his direction of these episodes did help to create, in collaboration with actor John Thaw, one of Britains best-loved TV detectives. It was this experience at the BBC that taught Boyle the basics of media production, working with modest budgets but within an organisation committed to high quality drama and with a reputation for social realism.

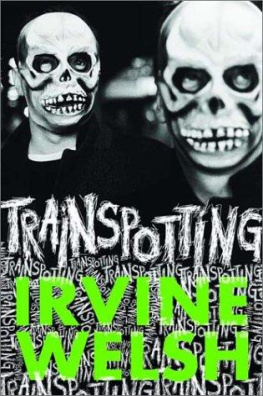

Boyle began his filmmaking career in 1994 with Shallow Grave, the first of three films made with producer Andrew Macdonald and writer John Hodge (Trainspotting was to follow in 1996 and A Life Less Ordinary in 1997). The first two of these, produced in collaboration with Channel Four Films, helped revive the British film industry, although the portrayal of drug-taking in Trainspotting provoked criticism and Boyle became characterised as a director interested only in gritty, working-class pictures. A Life Less Ordinary was an attempt to break away from this and to connect more directly with an American market. This brought its own problems: Boyle found that larger budgets and crews entailed creative compromises, something that was also to affect the follow-up film, The Beach, released in 2000. Both films were met coolly by critics and neither met the commercial expectations of Twentieth Century-Fox, now Boyles financial backer.

In 2001, Boyle took a step back from feature films, returning to the small screen to direct two small-scale, gritty dramas for the BBC: Strumpet and Vacuuming Completely Nude in Paradise. The break gave him the chance to re-group creatively and to experiment with lightweight digital cameras in collaboration with cinematographer Anthony Dod Mantle, an experience which directly contributed to the success of his next feature, the horror film 28 Days Later. Released in 2002, and backed by Fox Searchlight, Twentieth Centurys distribution arm dealing with more experimental and innovative filmmaking, it was a commercial and critical success. It also marked Boyles ability to move between a variety of genres with equal success, a tendency continued with Millions in 2004 and Sunshine in 2007. Millions failed to find its audience on general release, partly due to its ambition and partly due to the sad fact that an intelligent childrens film is something of a generic rarity. The science fiction of Sunshine was more successful but took a long time to bring to the screen - the creation of a complete fictional universe was an experience which Boyle found exhausting and probably not one which he would want to repeat any time soon.

Still with Fox Searchlight, Boyle teamed up with writer Simon Beaufoy, whose work he admired, particularly on The Full Monty (dir. Peter Cattaneo 1997), to create Slumdog Millionaire in 2008. Vikas Swarups 2006 novel Q&A had been a bestseller and Boyle leapt at the challenge, intrigued not so much by a narrative based on a TV show as the idea of filming a Bollywood-style love story in India. The film was a huge success and led to eight Oscars in 2009, including Boyle as Best Director.

After much industry and media speculation, Boyle followed this up with 127 Hours in 2010, based on the true story of Aron Ralston, a climber and thrill-seeker who was partly trapped under a boulder for several days in the Utah mountains, and who had to face the dilemma of dying a slow death or cutting off his own arm.

There is little existing critical literature about Boyles work. Only one of his films to date, Trainspotting, has received individual book-length consideration. Martin Stollery (2001) and Murray Smith (2008) both write interestingly about the film, but their studies are fairly brief and do not use intertextuality as a critical tool. There is growing interest in Boyle himself, with two books of interviews published in 2011 (by Amy Raphael and Brent Dunham), but in a sense these act as something of a distraction from the raw material of the films themselves. Before this book, the only attempt to open out the field of studies into Boyles work has been Edwin Pages Ordinary Heroes: the Films of Danny Boyle (2009). Page takes an auteurist position and looks at the films for evidence of what he identifies at the beginning as the directors favoured themes and stylistic devices. The difficulty with this approach is that it assumes these themes are present in all his films and are readily transparent to every viewer, whereas I would argue that meanings in any visual medium are by no means undisputed or universal. It is important to remember that Boyle is telling stories, not delivering themes, and that seeing characters as carriers of messages can lead to reductionist assertions about the ultimate message of a film, such as Pages contention that money does bring happiness is the message of Shallow Grave and that Slumdog Millionaire is part of the university of life for all who watch it.

Next page