Contents

William Collins

An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers

1 London Bridge Street

London SE1 9GF

www.WilliamCollinsBooks.com

This eBook first published in Great Britain by William Collins in 2019

Copyright Adele Brand 2019

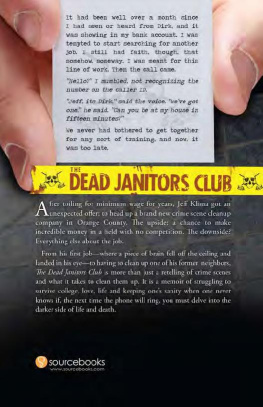

Cover design and text artwork by Jo Walker

Adele Brand asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins

Source ISBN: 9780008327286

Ebook Edition October 2019 ISBN: 9780008327293

Version: 2019-09-27

For my parents

CONTENTS

V ISUALISE A FOX: flame-orange on a white canvas, black paws and thick brush, pointed muzzle and diamond-sharp eyes. Now paint its native wildwood behind it this fox is trotting through the undergrowth, exploiting trails within the brambles trampled by badgers. It leaves neat narrow tracks on mud softened by afternoon rain, and snags its fur on thorns in passing.

Woodland, farmland, hedgerows and weary old trees. Owls, hedgehogs, rutting deer. Dead mans fingers that is, grisly-looking black fungi poking through sweet chestnut leaves in the autumn; woodpeckers playing rat-a-tat-tat on dying branches in the spring.

This is the classic British landscape of the classic British fox: the precious fragments of countryside saved from industrialised agriculture and overdevelopment. Ancient, intriguing, revitalising and poetic, our rural semi-wild has enchanted animal-focused authors from Beatrix Potter to Colin Dann of The Animals of Farthing Wood fame. The fox of tradition lives squarely within it, running under a cloud of mythology stirred by friend and foe alike.

But it is not the only fox of twenty-first-century Britain.

I MAGINE ANOTHER DUSK, this one after a day when chainsaws groaned and concrete mixers churned, and builders wolf-whistled at local women from a half-built rooftop. Woodland here is being transformed into a housing estate, rimmed by a newly built wall thick enough to please Hadrian, its bricks highlighted in passing by the headlights of commuter traffic.

A small vixen with a slender face and wary eyes tugs at chips dropped by the workmen, slicing artificially flavoured potatoes with enlarged molars called carnassials which define her species as a member of the Carnivora. She digs under the perimeter fence, and darts across the main road, feet fast and brush bouncing, passing me as I walk my dog. Ironic, perhaps, for wolves the ancestor of dogs once lived here too, feeding foxes through scraps of deer meat. The last Home Counties wolf was killed in Hampshire 800 years ago. The crowds returning from London have forgotten; perhaps the woodland has not. In an ecosystem, every extinction is like snapping a link in a chain.

But foxes themselves are in no danger of disappearing. Into a driveway the vixen turns, past trees native to China, through a side gate sealed against burglars, into a garden where another fox is burying Bakers Complete dog biscuits. The little vixen is an intruder in this territory. The resident flies at her, flipping her upside down, and skull-splitting screams theatrical, but bloodless pepper the night over the droning of the traffic.

She struggles free, and bolts back across the road into the fragmented woodland. Her motive for this daring if ill-fated trespass is obvious: she is lactating and needs food and water to produce milk for her cubs. She is driven by an unquenchable instinct to survive.

T HAT WAS LAST YEARS DRAMA.

I havent seen that particular vixen for a few days; it is mid-March as I write this, and doubtless she is underground with a new litter. She has survived the last twelve months despite her wood being turned into houses with million-pound price tags, and despite the best efforts of the neighbouring fox group to keep her out of the garden. Her body language is tenser than theirs, her eyes a little sharper, and her habit of poking her muzzle through gaps in the fence never fails to amuse.

This is not the city; it is Surreys battered greenbelt. Despite the developers stalking the county like thieves eyeing up wallets, we still have rich and abundant wildlife between the golf courses, out-of-town supermarkets and ever slower M25. Yet only a few miles north of the endangered wildflowers thriving on our chalky hills, the mood changes. London town spikes our northern horizon with towers, giant wheels and an orange nocturnal haze. Somehow, once there, we consider it unremarkable that we have grown buildings taller than trees.

It is undeniably beautiful, that old city filled with lion statues. History smiles from every spire and road name, grand, grotesque or tragic. You fall into the rhythm of it: the river of people flowing from Victoria station in the mornings, the shouts of Big Issue sellers, tourists photographing themselves in St Jamess Park. Cyclists speeding across pelican crossings, strangers apologising in the street when you bump into them, anti-war protesters perched on window frames with placards while weary police keep watch it is such a human place.

Human, but full of foxes. Many thousands of them live in urban environments in Britain, from London to Edin- burgh.

We jolt at that, sometimes alarmed, sometimes happy that a being of the ancient wildwood can find a home in Britains sprawling capital it feels a little out of sync, like an Elizabethan lady in ballroom dress among the revellers in All Bar One. The contrast between free wild animal and hard concrete street is vivid, irresistible, burning a place in our collective consciousness. Fed on television images that associate wildlife with wilderness, this displacement of normal can beget either wonder or fear. Perhaps the social reserve in the British psyche leaves us puzzling over the correct etiquette. Upon seeing a fox, many people are not quite sure what to say.

So, instead, we have put the fox in the dock for questioning. We have accused it of trespassing into the human domain, of being cheeky, of spreading disease, harming pets, and even posing a significant risk to ourselves. Unperturbed, the fox strays ever further into our world, permeating our language, pop music, movies, pub names and television adverts. They are debated in offices, schools and Parliament. One was recently filmed by bemused journalists outside 10 Downing Street as they awaited the appearance of the prime minister. Another found fame climbing 72 floors of the Shard, and lives on in that monoliths merchandise. Others have trotted onto the pitch in the middle of high-profile football matches.