Contents

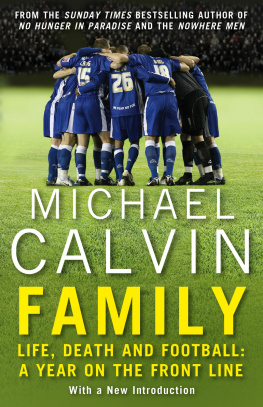

The Nowhere Men

Michael Calvin

To my children, Nicholas, Aaron, William and Lydia. Follow your dreams.

Acknowledgements

Scouts are never off duty. Ive just come off the phone from Mel Johnson. I mentioned in passing that I am due to attend the final game at Underhill, Barnets idiosyncratic little ground for the past 106 years. Ah he said. You can do me a favour. Theyre playing Wycombe. Can you give me a report on their keeper? A lad called Ingham. Hes 18, six two, six three, played about half a dozen games. Im hearing good things. Ill try to watch him on the last day of the season.

Coincidentally, I had spoken earlier to John Griffin. He told me Peter Taylor was scouting Charles Dunne, Wycombes full back, for the England Under 20 squad, and raved about Matt Inghams potential. We had him out at Oxford City for eight months, and hes only been in the first team for six weeks, but we are going to lose him he said. Im already digging in the dirt for the next one.

Mel Johnson was described by Caroline Shea, PA to QPRs last 34 managers, as the nicest man in football when she took me for a cup of tea before one of the countless interviews for this book. Griffin runs him close, but, in truth, there were few scouts to whom I did not warm. I thank everyone who gave me their time and their trust. Im especially indebted to Jamie Johnson, Mels son, who gave me the idea for this book during a casual conversation in the managers office at Millwall. I hope my respect for their trade, and my interest in the tangential issues touched by the recruitment process, shines through.

You would not be reading this without the support I have received from Ben Dunn. I value his wisdom and foresight, which are unusual traits for a West Ham supporter. His team at Century are of Champions League quality. Thanks, so much, to Julia Twaites, Bela Cunha, Glenn ONeill and Natalie Higgins. The legal advice of Duncan Calow was invaluable. My literary agent, Paul Moreton, has also been hugely supportive.

At one stage in the process, I was overwhelmed by the volume of information I had accumulated. Enter, stage left, my guardian angel, Caroline Flatley. My former PA at the English Institute of Sport was in the process of leaving the BBC for an executive role at British Cycling, but found time to transcribe the final 27 hours of interviews. A Northern lass like her, attempting to decipher the Bristolian burr of Gary Penrice, redefined culture shock.

I retreated to the Cornish village of Nancledra, and Smithys Cottage, to shape the opening chapters. Thanks to Margaret and Mark Taylor, for tolerating this unshaven hermit, whose body clock had exploded. Thats why, above all, I need to recognise the support of my family. Quite how my wife Lynn has lived with me during the gestation period of this book is beyond me. She has had more broken nights with me, in writing mode, than with any of our children, Nicholas, Aaron, William and Lydia.

I promise I wont put you through it again, until the next time.

Michael Calvin April 2013

1

The Initiation

MEL JOHNSON TOOK his tea, without milk or sugar, and sat with his back to the wall, at the circular table closest to the door. His eyes moved quickly, constantly, as he completed his risk assessment. He was friendly and attentive, but there were 83 other scouts in the first-floor room at Staines Town. It was his business to know their business.

A wry grin. He noticed Bullshit Pete was sitting alone, chasing a piece of chicken around his plate. Buffet Billy was working his way through chips, rice and a curry which had the colour and consistency of melted caramel. The Ayatollah was in a conspiratorial huddle with his followers, whose synchronised glances offered clues about the nature and direction of their discussion.

Agents circulated, seeking the convertible currency of casual gossip and inside information. One, nondescript in appearance apart from a lilac roll-neck sweater, was identified by Johnson as Billy Jennings, a striker who helped West Ham win the FA Cup in 1975. His bottle-blond mullet, a feature of my schoolboy scrapbook, had receded to a monkish semi-circle around the ears.

Emissaries from the international game Brian Eastick, Englands Under 20 coach, and Mark Wotte, Scotlands performance director held court. The room hummed with conjecture and cautious conversation. It had the feel of a bookmakers on an urban side street. The men, largely middle aged and uniformly watchful, had the pallor of too many such mid-winter nights on the road.

I had invited myself into their world, a place of light and shadow. They were the Nowhere Men, ubiquitous yet anonymous, members of footballs hidden tribe. The elders, like Johnson, had paid their dues at the biggest clubs. Initiates were paid 40 pence a mile, and informed decisions on players worth 10 million or more. All were under threat from technology and the new religion of analytics.

Such men are central to the mythology of modern football. Scouts may be marginalised, professionally, but they possess the power of dreams. There is no textbook for them to follow, no diploma they can receive for their appreciation of the alchemy involved in the creation of a successful player. Their scrutiny is intimate, intense, and highly individual. They must balance nuances of character with aspects of pre-programmed ability, and fit them to the profile and culture of the clubs they represent.

Everyone knows what scouts do, but no one truly understands why they do it, and no one knows who they are. Their anonymity is anathema to the modern game, a gaudy global carousel which invites examination on its own, highly lucrative terms. Scouts supply the star system, but remain resistant to it. At best, they are indistinct figures, judged on false impressions like old-school golf caddies, who were assumed to drink heavily and sleep in hedges. They are an enclosed order, by circumstance rather than philosophy.

Anyone who has ever stood, shivering, on a touchline or sat, shouting, from the back of a stand thinks they can do their job. Whether the average football fan would want to commit to such a disconnected lifestyle is another matter entirely. Being paid for watching up to ten games a week might be the sort of fantasy which sustains a fourth former during an afternoon of algebra, but the hours are long, and family unfriendly. Scouts eat on the run, live on their nerves, and receive a relative pittance.

This may seem counter intuitive, but I resolved to study them, and to share their experiences, because I believed in the essential romanticism of their role. Over the course of more than a year on the road, I was seduced by the process of discovery. I saw boys whose precocity caused time to freeze, and young men, in straightened circumstances, who seized a second chance to shine. I was there when the seeds of natural talent began to germinate; this may occur in a park, or on a non-league gluepot. It may be destined to flower in one of the cathedrals of the game, but it beckons only those who comprehend its potential.

Scouts are nowhere, and everywhere. They are rivals, but mix closely. They offered me an insight into the idiosyncrasies and insecurities of an incestuous community. Their judgements are severe, occasionally unkind, but they must be judged in the context of a game which has an unerring habit of brutalising its participants. What makes scouts different? Time and again Paul Newmans line, delivered in his role as Butch Cassidy, in the film Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, came to mind:

I got vision, and the rest of the world wears bifocals.

On this particular Wednesday night, February 15, 2012, Chelsea were playing West Ham in the third round of the FA Youth Cup. Teenagers, courted and cosseted before adolescence, were accustomed to indulgences, such as being transported to Wheatsheaf Road in the first teams luxury coach. They filed, with studied indifference, through the tiny car park, past the picture window of a gymnasium which framed suburban wage slaves purging themselves on treadmills.

Next page