Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

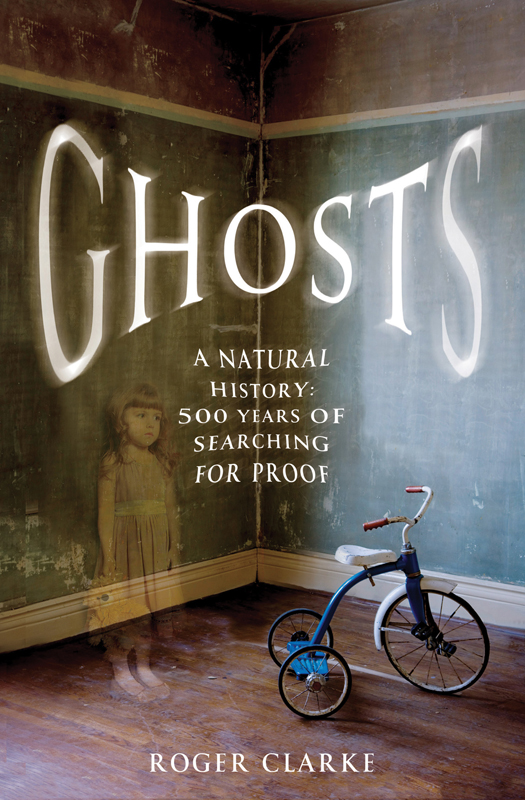

For my mother, Angela H. Clarke, who saw a ghost

List of Illustrations

My Haunted Houses

O death, rock me asleep,

Bring on my quiet rest

Let pass my weery guiltless ghost

Out of my careful breast.

said to have been written by Anne Boleyn, in the Tower of London before her execution

There was a dead woman at the end of the passageway. I never saw her, but I knew she was there. The passage was at the top of the stairs, leading to the left, to the spare bedroom and my parents room. The end was always in shadow. Even at the height of summer I greatly disliked it. Returning from the village school in the mid-afternoon, I was alone in the house. Every day I delayed the rise up the stairs until it became a mad dash to my bedroom, eyes clenched shut, hands cold.

We lived in a seventeenth-century former rectory, a thatched cottage with roses rambling up its west side and garden walls of great antiquity. It was the 1960s, and on the Isle of Wight it was still an England Thomas Hardy would have recognized. It was immemorially rural. The village school had a holiday for the annual agricultural show. Many of the children had parents working on farms.

At school, the dinner lady used to tell us stories. I absorbed a certain amount of them there was the ghost of a Roman centurion in a wood on the approach to Bembridge, and a spectral horseman who foundered in the marshes near Wolverton, a place cut through by a clean-running stream where we would go on nature walks.

I began to devour books on the subject. Among the most intriguing things I learnt, as it was repeated many times over, was that there were more ghosts per square mile in England than in any other country in the world. But why should this be the case?

My mother, noticing my growing fascination with the subject, mentioned that she had seen a ghost at the end of that passage at the top of the stairs. A friend, visiting, had seen her too. The ghost had entered the spare room while she was lying in bed. At breakfast, the question was asked: Who is she? Whoever she was, her energies seemed to dissipate when alterations to the house were made.

Still, she hung in my mind.

* * *

When I was fifteen, we moved to an even older building, a manor house that had once belonged to a Norman Abbey; it too was haunted. The last pagan king of the Isle of Wight was buried in the woods on the hill nearby. By the pond, an old yew tree had grown against a millstone, like a finger swelling round a wedding ring. There was decayed panelling in one room. Smugglers marks in the form of sailing ships were carved in the chalk of the medieval dovecote.

You could hear the ghosts a man and a woman talking inside the house sometimes; it was as if someone had put the radio on. The dogs growled at a particular spot in the kitchen. There were ghosts outside too. My fathers horse shied at the chalk pit a few hundred yards away, in the lea of Shalcombe Down. A flying boat had crashed there in 1957, on the way to Majorca, full of honeymooning couples. Forty-five people died. Horses still dont like the chalk pit, Im told. At the top, near the line of fir trees, lies a scree of twisted metal under the forest grass.

The spare bedroom wasnt a good place to sleep. Bodies from the wreckage had been brought up via the stone steps outside, and for a day or so it served as a temporary morgue.

I thought about ghosts and ghost-hunting all the time. There were lots of books about people seeing ghosts, but almost nothing about what ghosts might be. Some ghosts seemed aware of the living, and others did not. I began to correspond with the people whose books I read with such passion.

One was the ghost-hunter Andrew Green. He believed that ghosts were either caused in the brain by electrical fields or were electrical fields. A humanist, he was noted for his good-hearted scepticism, and became the literary archetype of the doubting boffin assailed by genuine ghosts in which he does not believe. I also corresponded with Peter Underwood, author of dozens of books on ghosts, who ended up quoting some of my theories in his autobiography, No Common Task (1983). I found myself as a teenager in the acknowledgements of books by both Green and Underwood, then the two best-known ghost-hunters in England. I became the youngest member of the Society for Psychical Research when I was fourteen, proposed by Andrew Green.

I still hadnt actually seen a ghost, though. It was becoming tiresome.

* * *

Between 1980 and 1989 I visited four places said to be haunted: the Tower of London, Knighton Gorges on the Isle of Wight, Sawston Hall in Cambridgeshire and Bettiscombe House in Dorset, famous for its screaming skull.

The Tower of London is and was a death zone. It reeks of death, at night. The severed head of a mythical king rests beneath it. The original White Tower, built with forced labour in 1077, was an edifice of malice intended to intimidate the population of London. For a large part of its history, the Tower of London was a royal residence; then it became a prison, particularly for those convicted of treason, with graded cells, from Anne Boleyns quarters to a notorious cell called Little Ease, where you could not stand and you could not lie down. In medieval times, a husband-and-wife blacksmith team lived there; he made the torture instruments and she the shackles and manacles.

By day, its a kitsch tourist venue of great popularity; by night, a high-security establishment guarded by members of the regular British Army. Ghost sightings are common among the small community living there. In 1957, a young Welsh guardsman named Johns saw a shapeless form on the Salt Tower at 3 a.m. which slowly bloomed out of the cold damp air with the face of a young woman. An officer from his regiment later commented, Guardsman Johns is convinced he saw a ghost. Speaking for the Regiment, our attitude is All right, so you say you saw a ghost lets leave it at that.

There is only one book written on the Tower of London ghosts, and that book was written by a Yeoman Warder named George Abbott. Abbott spent thirty-five years in the RAF as an NCO before donning the Tudor undress uniform of the warders in 1974. He wrote four books on different aspects of the Tower, the best known of which is on torture instruments, and after he retired he was occasionally to be seen sporting a resplendently long warderine beard and dropping chilling, dry facts into documentaries about torture.

One autumn evening in 1980, aged sixteen, I found myself at the Middle Tower just as the last of the hundreds of daily visitors had left and the gates were closing. George Abbott was waiting for me there, and we went in. It was dark. The Tower had a kind of airy vastness about it I hadnt expected. Without tourists, it hovered in time. Near the Bell Tower, we were challenged by a sentry to identify ourselves before entering through the heavy bolted door of the Bloody Tower. We were in a version of darkness, with no light bar that from the white phosphorescent security lights on Tower Green, which cast a magic-lantern show of trees moving in the wind against the old walls. Abbott pointed to a darkened corner where the little Plantagenet princes had lain, perhaps, before their assassins entered from the battlements. I kept looking at the door. It seemed about to open, all the time. So much of the ghost story is the anticipation.