Contents

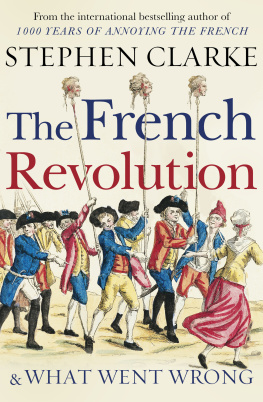

About the Book

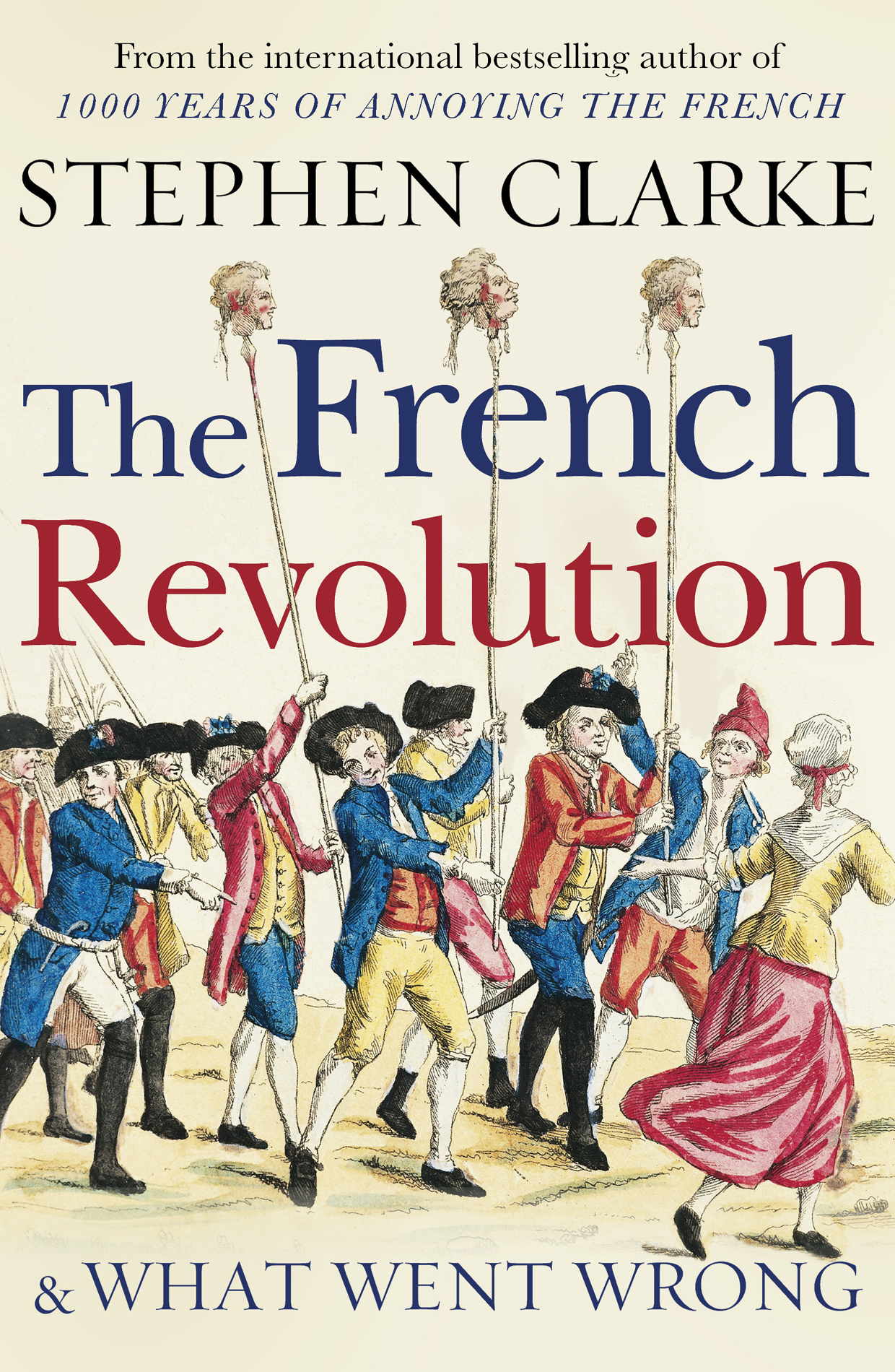

Legend has it that, in a few busy weeks in July 1789, a despotic king, his freeloading wife, and a horde of over-privileged aristocrats, were displaced and then humanely dispatched.

In the ensuing years, we are told, France was heroically transformed into an idyll of Libert, Egalit and Fraternit.

In fact, as Stephen Clarke argues in his informative and eye-opening account of the French Revolution, almost all of this is completely untrue.

In 1789 almost no one wanted to oust King Louis XVI, let alone guillotine him.

While the Bastille was being stormed by out-of-control Parisians, the true democrats were at work in Versailles creating a British-style constitutional monarchy.

The founding of the Republic in 1792 unleashed a reign of terror that caused about 300,000 violent deaths.

And people hailed today as revolutionary heroes were dangerous opportunists, whose espousal of Libert, Egalit and Fraternit did not stop them massacring political opponents and guillotining women for demanding equal rights.

Going back to original French sources, Stephen Clarke has uncovered the little-known and rarely told story of what was really happening in revolutionary France, as well as what went so tragically and bloodily wrong.

About the Author

Stephen Clarke lives in Paris, where he divides his time between writing and not writing.

His Merde novels have been bestsellers all over the world, including France. His non-fiction books include Talk to the Snail, an insiders guide to understanding the French; How the French Won Waterloo (or Think They Did), an amused look at Frances continuing obsession with Napoleon; Dirty Bertie: An English King Made in France, a biography of Edward VII; and 1000 Years of Annoying the French, which was a number one bestseller in Britain.

Research for The French Revolution and What Went Wrong took him deep into French archives in search of the actual words, thoughts and deeds of the revolutionaries and royalists of 1789. He has now re-emerged to ask modern Parisians why they have forgotten some of the true democratic heroes of the period, and opted to idolize certain maniacs.

Follow Stephen on @SClarkeWriter and www.stephenclarkewriter.com

Also available by Stephen Clarke

F ICTION

A Year in the Merde

Merde Actually

Merde Happens

Dial M for Merde

A Brief History of the Future

The Merde Factor

Merde in Europe

N ON-FICTION

Talk to the Snail: Ten Commandments for

Understanding the French

Paris Revealed

Dirty Bertie: An English King Made in France

1,000 Years of Annoying the French

How the French Won Waterloo or Think They Did

Le Chteau dHardelot, Souvenir Guide

E B OOK SHORT

Annoying the French Encore!

For more information on Stephen Clarke and his books, see his website at www.stephenclarkewriter.com or follow him on Twitter @sclarkewriter

In general, may we not say that the French Revolution lies in the heart and head of every violent-speaking, of every violent-thinking French Man?

Thomas Carlyle (17951881), Scottish writer, in The French Revolution: A History (1837)

Toute rvolution qui nest pas accomplie dans les moeurs et dans les ides choue.

Any revolution that does not have sufficiently complete morals and ideas will fail.

Franois-Ren de Chteaubriand (17681848), French writer and politician, in his Historical, Political and Moral Essay on Revolutions Ancient and Modern (1797)

La rvolution est comme Saturne elle dvore ses enfants.

Revolution is like [the Roman god] Saturn it devours its children.

Pierre Victurnien Vergniaud (175393), French politician who pronounced the death sentence on Louis XVI in January 1793 and was himself guillotined ten months later

Fluctuo nec mergor. To all those responsible, merci.

INTRODUCTION (AND JUSTIFICATION)

I MUST START by stressing that I am not a French-style royalist. People who seriously hope that France will one day be ruled again by the descendants of Louis XVI or his relatives are usually so anti-democratic that they regard a British monarch as a dangerous leftie and a heretical Protestant.

Many of these modern-day French monarchists also believe that anyone who cant trace their ancestry back to Asterix the Gaul should be deported from France.

For obvious reasons, I am definitely not one of those.

Having said that, there is a lot of romantic nonsense talked and written about the French Revolution mainly by the French themselves.

Listening to these revo-mantics, one would think that in the space of a few weeks in 1789, every powder-faced aristo was forced to donate his or her wealth to the starving masses; every lazy landowner was dispossessed in favour of a worthy producer of handmade goats cheese; and a despotic king and his free-loading wife were displaced (and then humanely dispatched) to make way for a benign bunch of philosophy-reading democrats who gave Libert, galit and Fraternit to everyone in France.

But almost all of that is almost entirely false. And the aim of this book is to explain why.

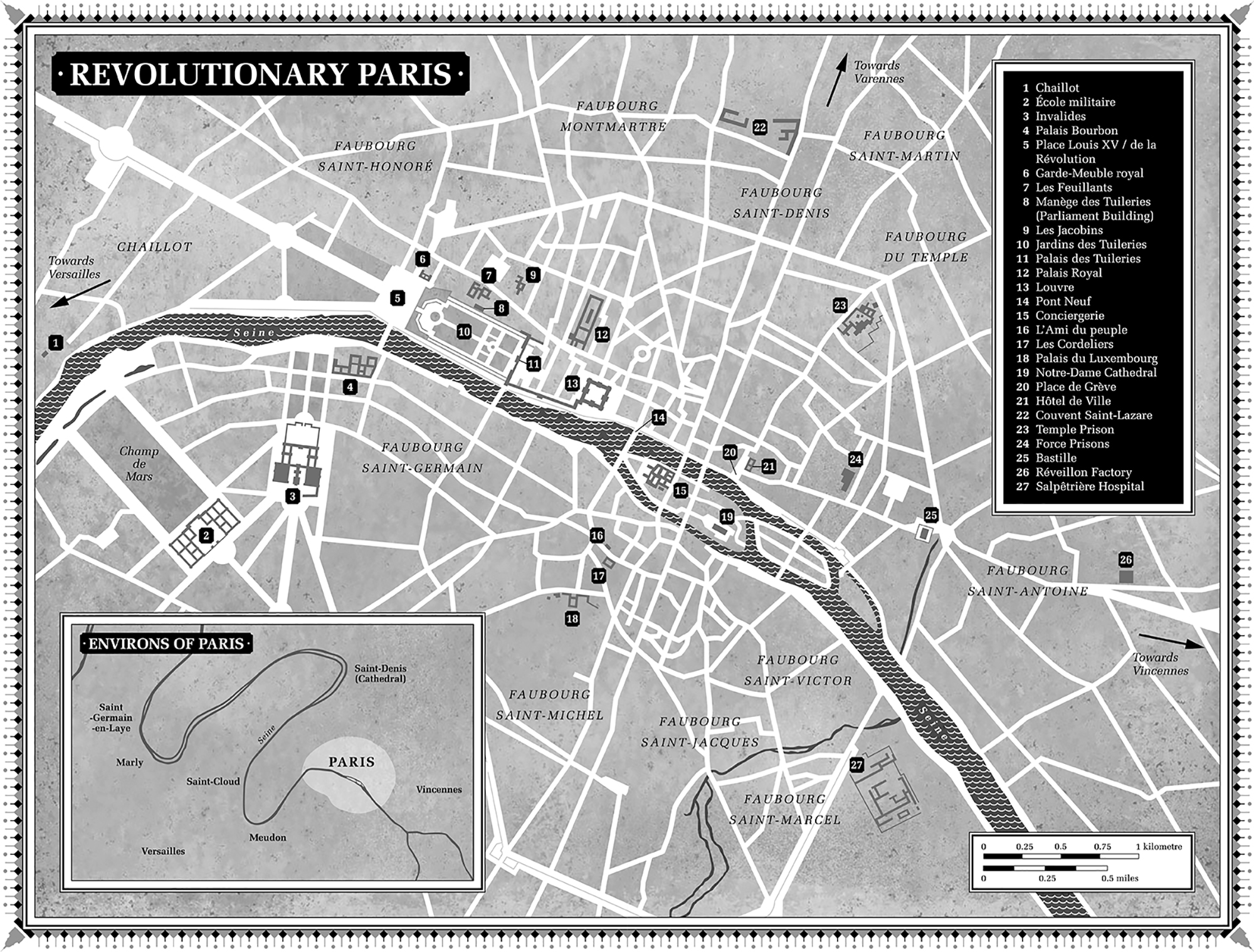

Libert, galit and Fraternit may have been the initial aims of the Revolution, but for several years the reality was more like Tyranny, Megalomania and Fratricide. And what the French rarely acknowledge, or even realize, is that guillotining royals and aristos was not at all what their revolutionaries originally intended. The fact is that even during the storming of the Bastille, almost no one in France was calling for King Louis XVI to be deposed, let alone decapitated.

The truth is that even before 14 July 1789, a revolution had taken place, and a new, egalitarian Constitution was being drafted by a more or less democratically elected parliament (if male-only suffrage can be called democratic). This Constitution overtly reaffirmed Louis XVIs position as head of state. He was far from happy with some of the changes being imposed upon him, but he accepted them, and began to work with the new government on creating a reined-in, English-style monarchy.

What was more, once his wife Marie-Antoinette had been forced to stop spending the GDP on parties and necklaces, and the aristocrats were no longer able to tax their peasant tenants to death, Louis XVI was very popular with the average Franais and Franaise. He was the star guest at the ceremony to mark the first anniversary of Bastille Day, during which a mass oath of allegiance was sworn to both king and nation.

Louis XVIs attendance at the ceremony was heartily cheered by the Parisian crowds the same people who had spent much of the previous summer rioting. Most ordinary citizens felt that, without the stalling tactics of the aristocrats, Louis would have given them fairer taxation and even a measure of political influence years earlier. This was why in 1790, the King was still seen by the general population as a potential benefactor, a figure of hope.