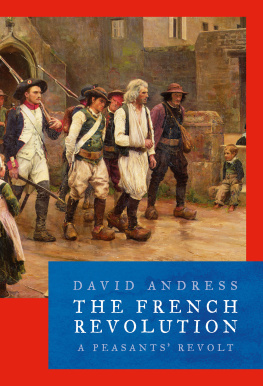

THE FRENCH REVOLUTION

A Peasants Revolt

David Andress

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

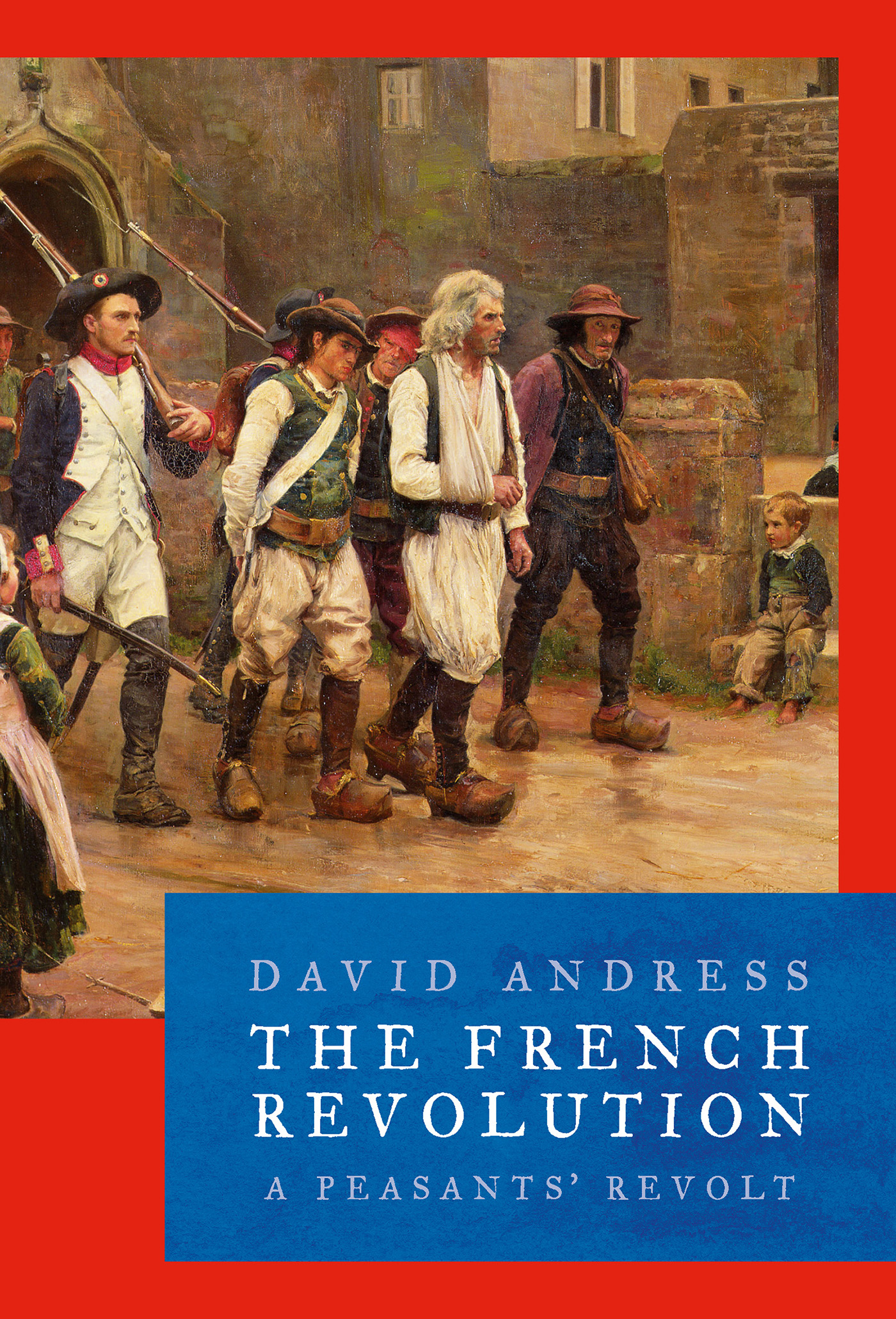

Jules Girardet, The Rebels of Fouesnant Returned to Quimper by the National Guard in 1792

Alamy Images

This is an Apollo book, first published in the UK in 2019 by Head of Zeus Ltd

Copyright David Andress 2019

The moral right of David Andress to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act of 1988.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of both the copyright owner and the above publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN ( HB ) 9781788540070

ISBN ( E ) 9781788540063

Designed by Isambard Thomas

Cover image: The Revolutionaries of Fouesnant Rounded Up by the National Guard in 1792, c.1886-87 (oil on canvas), Girardet, Jules (1856-1946) / Musee des Beaux-Arts, Quimper, France / Bridgeman Images

Head of Zeus Ltd

First Floor East

58 Hardwick Street

London EC1R 4RG

WWW.HEADOFZEUS.COM

Contents

On 12 July 1789, as Parisians were launching an insurrection that would stun the civilized world, the English writer Arthur Young was travelling alone to the east of the capital, on the road between Verdun and Metz. Engaged on a tour dedicated to exposing and critiquing the shortcomings of French agronomy, particularly in comparison to Britain, Young filled the daily journal he kept with scathing observations on the poverty of the land around him, and the folly and ignorance of its people.

Walking his horse up a hill between the villages of Les Islettes and Mars-la-Tour, he fell into a conversation that was to become a staple of historical accounts, for by its timing and content it was almost too perfect. A poor woman, who complained of the times, and that it was a sad country gave him details of the burdens her familys farm had to support, in taxes, tithes and other dues, and provided Young with the opportunity for some sententious commentary:

This woman, at no great distance might have been taken for sixty or seventy, her figure was so bent, and her face so furrowed and hardened by labour, but she said she was only twenty-eight. An Englishman who has not travelled, cannot imagine the figure made by infinitely the greater part of the countrywomen in France; it speaks, at the first sight, hard and severe labour: I am inclined to think, that they work harder than the men, and this, united with the more miserable labour of bringing a new race of slaves into the world, destroys absolutely all symmetry of person and every feminine appearance. To what are we to attribute this difference in the manners of the lower people in the two kingdoms? TO GOVERNMENT.

The womans words that Young recorded before this judgement are those which seemed to have the greatest prophetic quality: It was said, at present, that something was to be done by some great folks for such poor ones, but she did not know who nor how , but God send us better, for the taxes and the dues are crushing us .

Recorded two days before the storming of the Bastille, these words seem to reach out of history as a plaintive plea from the masses, imprisoned in misery, crying out to be liberated. But they are, in themselves, more extraordinary than that. They imply, perhaps disingenuously spoken after all to a mysterious foreign stranger an ignorance of the ferment that had filled the countryside since the previous winter, a passivity wholly at odds with events taking place across France, and a deference that was quite the opposite of the way peasant communities were literally taking up arms to free themselves from their crushing burdens.

A few months previously, the inhabitants of Rouffy, a village further west near the regional capital of Chalons, had put in writing their demands for, among other things, new and fairly apportioned property taxes, the abolition of taxation on goods, the eradication of abuses in public administration, the institution of free justice, and for priests who took money from the tithe to be obliged to use it properly to maintain their churches and the ornaments, books, fabrics and sacred vessels, and to give alms in proportion to their tithes.

At the same time, the villagers of Achain, a days ride southeast of Metz, had set out their demands, including this categorical claim:

All those rights having their origin in the painful times of the feudal regime, when lords imposed on their subjects any yoke that pleased them, can be considered as true abuses, we request their reform: the province of Lorraine, being joined to France, asks to enjoy all the same privileges as the French, and to be free.

Dozens of other villages within a few days travel had made similar claims, hundreds within each province, several tens of thousands across the country. The landscape that Arthur Young rode across, bemoaning at each halt its lethargy and backwardness, was already breeding a revolution.

*

There is something uniquely scornful about the English word peasant . It has become detached from the root that still clings visibly to the French paysan or the Italian paesano a person of the pays , the country; a local, or even, in the Italian version, a compatriot. The Spanish campesino points to a tiller of the fields, as do the old German terms Landsmann and Ackermann , while Bauer has come to mean farmer in an entirely modern sense. The historical movement that Arthur Young embodied is one reason for the particularly negative associations that cling to the English term.

A true peasantry, in the sense of communities living largely from their own lands, lacking any strong dependency on wider market relations, had been fading from the English countryside for over a century by the late 1700s. Agricultural improvement took many forms, but always circled around the creation of larger farms, controlled by landlords seeking a cash profit from higher yields for sale into urban markets, eradicating the customary ways of the rural community in favour of deploying labour under expert orders. In the minds of people like Young, this was unequivocally how one brought an entire society to higher levels of prosperity, unshackling the productive potential of the population to do other things besides feed themselves. Those who would seek to resist such universally beneficial change could only be mired in the past, uncivilized, perhaps even scarcely human: peasants!

From such a perspective, where only the cutting edge of progress really matters, the fact that over two-thirds of the French in 1789 were actual paysans working the land (and 80 per cent of the whole population was, one way or another, embedded in rural communities), or that French countryfolk had succeeded across the previous seventy years in increasing production to feed a population that had risen by a third, appears to mean little. And it is not only in the minds of scornful contemporary Englishmen that this is so. The French revolutionary elites themselves were conscious of their own aversion to the paysan , and promoted the word cultivateur as a more politically correct label. While they used that label as if it restored dignity to the downtrodden, many of them seem to have understood agricultural communities as little more than a receptacle for superficial idealism.