Also by David Andress

The Terror: The Merciless War for

Freedom in Revolutionary France

1789

1789

The Threshold

of the Modern Age

DAVID ANDRESS

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

New York

Farrar, Straus and Giroux

18 West 18th Street, New York, 10011

Copyright 2008 by David Andress

All rights reserved

Printed in the United States of America

Originally published in 2008 by Little, Brown, Great Britain

Published in the United States by Farrar, Straus and Giroux

First American edition, 2009

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Andress, David, 1969 1789: the threshold of the modern age / David Andress. 1st American ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-374-10013-1 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-374-10013-6 (hardcover : alk. paper) 1. EuropeHistory17891815. 2. United States History17831815. I. Title. D308.A63 2009 909.7dc22 2008044697 |

www.fsgbooks.com

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

AND AUTHORS NOTE

M y thanks go to all those involved in the production of this book, especially my agent, Charlie Viney, for some hard work on its initial shape and direction. Thanks to Tim Whiting at Little, Brown for taking the project on, and Steve Guise and Iain Hunt for work in the latter stages. To all my colleagues at Portsmouth, who continue to create a collegial work environment under pressures only we will ever know, and especially to Brad Beaven, without whom chaos would loom, many thanks. To all the various people who told me they were looking forward to seeing the finished product, I hope it was worth the wait; and to Mike Rapport special thanks for a late read-through and some crucial pointers.

To Hylda and Robert, Sheila and Michael, thanks for being there. To Jessica, with all my love as always, and to my darling girls, Emily and Natalie, for you, with love and hope.

Note:

For comparison of the various sums of money mentioned below, at the end of the 1780s one British pound was worth just under five US dollars, and somewhat more than twenty French livres. Note also that contemporaries had a habit of referring to England and Englishmen irrespective of the hybrid nature of Great Britain and its population. This is inevitably reflected in the source materials quoted here, but I have tried to keep my own text free of such prejudices.

1789

INTRODUCTION

Twas in truth an hour

Of universal ferment; mildest men

Were agitated, and commotions, strife

Of passion and opinion, filled the walls

Of peaceful houses with unquiet sounds.

The soil of common life was, at that time,

Too hot to tread upon.

William Wordsworth,The Prelude, 1805

W inter had come upon Europe like an apocalypse. The frosts had arrived early, and by November 1788 the land was thickly carpeted in snow. Far into the south of France the numbing cold had done its work, shattering the ancient olive trees and withering vines in the stone-hard ground. Nothing moved on the blizzard-buried roads, and rivers were frozen like iron. Cold was not the only portent of doom that had come from the skies. In the high summer a hailstorm had swept in from nowhere, ripping its way through the ripening crops across a huge swath of central France. Peasants had gazed on their ruined fields, well knowing the likely consequence, and by the end of that summer there had already been riots bred from a real fear of hunger. Now the whole of France looked out on the damage done by the awful cold, and could see only disaster ahead.

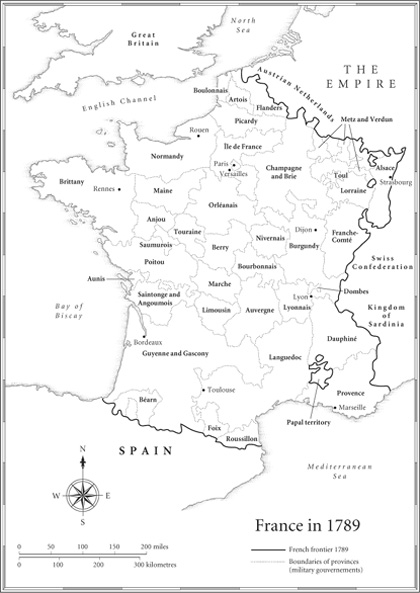

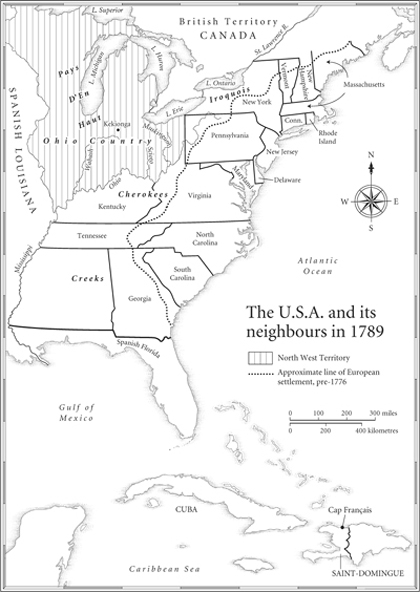

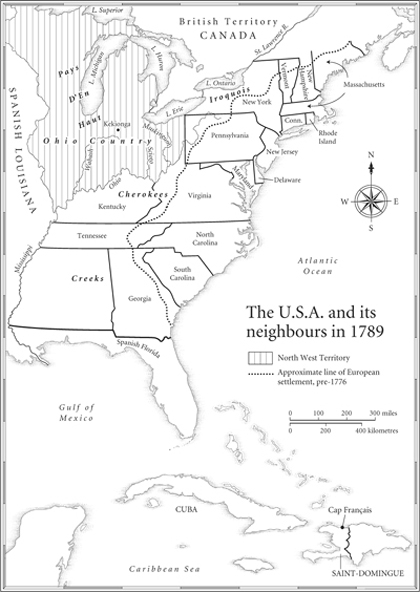

Late in January 1789, as an early thaw set in, turning the rivers to impassable torrents, the French were summoned from their firesides to meet in every parish in the land, there to answer the call of King Louis XVI to send him delegates for an Estates-General. No one had an inkling of what such an event might produce the last had happened 175 years earlier. For all that time, the will of the king had been enough to give the country new laws, and to wrestle taxes from its recalcitrant population to fight in Europes endless succession of wars. Now, by a remarkable twist of historical irony, a war embarked on to help free Britains American colonists from the imperial grip had left the aristocrats of France fiscally exhausted. The countrys coffers were drained by ruinous loans to fund ships and soldiers, and government teetered on the verge of paralysis as age-old institutions locked horns with the king and refused to cede new taxes.

Judges and lawyers had pored over archaic records, deciding that the Estates-General, a meeting of delegates of Clergy, Nobility and Commons, was the only way to produce new laws that might wrest the country from its impasse of bankruptcy and fiscal deadlock. They also knew that to summon the Estates was to invite the grievances of the population, and so the kings official proclamation had been explicit: His Majesty wishes that everyone, from the extremities of his realm and from the most remote dwelling places, may be assured that his desires and claims will reach Him. Thus tens of thousands of nobles, clergymen, lawyers and merchants, hundreds of thousands of townsfolk, and millions of peasants, trudging through slush and mud to their village churches, prepared to unleash upon the Crown of France the weight of their troubles. From their current material suffering, from long reflection on the inequities of an aristocratic society riddled with traces of feudal exactions, from the reverberations of a century of new enlightened thought, and not a little from the echoes of revolutionary events across the Atlantic, the French were about to create the conditions for the traumatic birth of modern Europe.

Far to the north, in comfortable lodgings amid the deep snow of Yorkshires Pennine Hills, one man knew a great deal about the power of grievances to change history. Thomas Paine was approaching his fifty-second birthday after a life full of incident that was only just about to launch into its most turbulent episode. Paine was from humble roots, the son of a Norfolk stay-maker, and after failed careers as a privateer and excise man had landed in Pennsylvania fifteen years before, just as the fires of American independence were being stoked. Eager to put his pen to work in this new cause, and ever keen to provoke controversy, he gained instant fame with Common Sense, a pungent tract in favour of the colonials liberty. As the conflict unfolded, Thomas Paine had documented it in a series of broadsides he called The American Crisis, lambasting both the British enemy and divisions in the rebels ranks. Summoning new strength with his pen, he was the Americans most able propagandist, a man who could justly claim to have brought an empire low with his words.

But now, as 1789 dawned, Paine was working to build, not to destroy. A long-nosed seeker after quarrels, his piercing black eyes always questing after dispute, he had a difficult reputation, not helped by a fondness for the bottle that every enemy, past and future, was to harp on. Paines almost pathological inability to be diplomatic had made him enemies among the new American elite, and he had taken refuge from politics in the realm of engineering. The sharpness of his disputatious intellect was not confined to politics, and modern techniques of forging iron had given him inspiration for a new kind of bridge, a low arch that might be cast across spans of hundreds of feet. Weather such as that now devastating France was common in the northern United States, where bridges built on pilings soon clogged with winter ice. Paines bridge would soar above such difficulties, but even in a new young land, ripe for innovation, he could not persuade anyone to invest in his scheme, and remarkably, given his radical history, Paine had turned to the monarchies of old Europe for help.