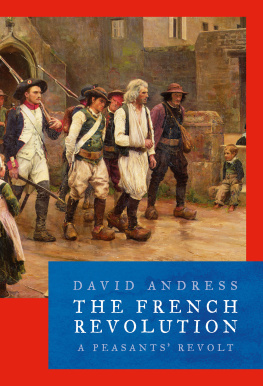

CULTURAL DEMENTIA

David Andress

AN APOLLO BOOK

www.headofzeus.com

David Andress argues that we are suffering from an attack of social and cultural dementia.

The former great powers of the historic West especially Britain, the USA and France seem to be abandoning the wisdom of maturity for senile daydreams of recovered youth. Along the way they are stirring up old hatreds, giving disturbing voice to destructive rage, and risking the collapse of their capacity for decisive, effective and just governance. At the core of this dangerous turn is an abandonment of political attention to history, understood as a clear empirical grounding in how we reached our present condition. Historical stories are deployed in public debate as little more than dangerous fantasies.

In this blistering assessment David Andress, one of Britains leading historians of the age of revolutions, shows how the West has abandoned its history and has lost its bearings and its memory.

Contents

To Robert Andress

This book argues that recent political events place the UK, France and the USA in a state of catastrophic cultural dementia. That is a very strong term, and I mean it absolutely seriously. It is not an image to be deployed lightly. My own father died of Alzheimers in May 2015; most peoples families now include at least one similar story of terrible decline. It is precisely because what confronts us now risks being an equally horrifying slide into dissolution that the term is warranted here. And because a culture, unlike an individual, may hope to recover from its dementia, before it is too late.

Our current dementia takes the form of particular kinds of forgetting, misremembering and mistaking the past. In that sense it is not nostalgia, which is at root merely a form of homesickness for the remembered past. Nor is it, any more than an individuals dementia, a simple matter of amnesia. In most cases, the amnesiac is aware that they do not remember; and knowledge of that lack and of the potential to fill it from external information is something to cling to. The dementia sufferer is denied the comfort of knowing they dont remember.

By disintegrating a persons coherent recollection of their personal history, dementia strips them of their anchorage in the past. Who they were and who they are become muddled; their own identity and those of their loved ones become confused and dissonant. Situations cease to make sense, erupting unexpectedly into a mind that thinks itself in another time or place and cannot hold itself lucidly in the present. Anger, bitterness and horror coexist with fond illusion and placid self-absorption. Practical action becomes impossible. For many, there is a lapse into hallucination, delusion and paranoid suspicion of all around them.

Le Pen. Brexit. Trump. These might once have been the punchlines to a joke. But no more. The processes that have brought these names to global attention are nothing less than symptoms of rising cultural dementia. The former great powers of the historic West, now old in ways that cultures have seldom been before actually old, demographically speaking, in previously unthinkable terms seem to be abandoning the wisdom of maturity for senescent daydreams of recovered youth. Along the way they are stirring up old hatreds, giving disturbing voice to destructive rage and risking the collapse of their capacity for decisive, effective and just governance.

At the core of this is an abandonment of political attention to history, understood as a clear empirical grounding in how we reached our present condition. Historical stories abound; but as deployed in public debate they are often little better than dangerous fantasies, constantly at risk of abrupt and jarring collision with reality. Unlike Germany, for example, these countries have never undertaken the painful process of Vergangenheitsbewltigung : the coming to terms with the past that ceases to treat it as a comforting inspiration, and wrestles with the evils it conceals. Not even Germany, of course, has completed such a process irreversibly and entirely happily. Chancellor Merkels noble decision to open the nations borders to refugees in 2015 created a backlash that helped the anti-immigrant, conservative-nationalist Alternative fr Deutschland party to a poll breakthrough in the 2017 Federal elections. However, as has been the case with many far-right movements across Europe, the AfDs breakthrough only netted them one in every eight votes well below the almost one in five shared by the major forces at the other end of the spectrum, Die Linke and Die Grnen.

The presence of groups such as the AfD is an unpleasant component of the new normal of global politics, but so far has not produced any dangerously disruptive systematic consequences. Until these groups and their toxic messages are able to claim 30 per cent or more of the vote, we can still reasonably hope that the centre in Germany and elsewhere will hold. By the same token, looking further afield, the manipulation of democratic structures and aggressive chauvinism that Russia regularly deploys is, in the long term, more normal than not for a state that has struggled to tolerate a real civil society at any point in its history. Much like the ruthless control still exercised by the Chinese Communist Party, we can consider it to be deplorable but not catastrophic.

France, the UK and the USA, however, are supposedly the collective cradle of Western democracy, the nations that, quite literally, created the culture of codified constitutions and rights on which the Universal Declaration of Human Rights was based. Even if, as we shall see, such a self-image has often been little more than an illusion, it has been a uniquely powerful one not least in fuelling unhesitating global military and political interventions by all three countries. The current condition of these nations, challenged by powerful bottom-up movements that question all their previously assumed values of openness, does have the potential to be uniquely catastrophic, at least for those of us trapped within these states if not more widely still. How any part of the world would sustain support for democracy if all five permanent members of the UN Security Council were to become open, convinced and militant chauvinists is a question that does not bear too much reflection.

Until recently, continued global economic and cultural leadership spared politicians in Washington, London and Paris from the need to confront where their national wealth came from, or how their languages came to dominate the world. Comforting illusions of progress concealed worsening symptoms of relative decline and internal divisions amounting to gross injustice. As economic progress has so visibly come to a halt in the past decade, stripping away that illusion of inexorable improvement, delusion has taken its place. Declarations that immigration can simply be halted, that long-dead industries can be restarted, that crumbling infrastructure can be replaced overnight, and a generous welfare state upheld and extended for the right sort of citizens, have abounded.

These claims, coming from the right and the far-right of the political spectrum, draw the natural condemnation of others further to the left. But it is important to recognise that this is not merely a continuation of old ideological struggles: these developments are even more dangerous because they are self-destructively mistaken. They are detached from the actual history of how our societies took on their current social, economic and cultural forms; and they are wrong about where those societies fit into the world around them. They make no more sense than a dementia sufferer demanding that his carers let him get the train to work in his pyjamas. Just as a confused eighty-year-old cannot bend the world to his perception, so a Brexiting Britain or Great Again America cannot return old prosperity to their rustbelts by willing it to happen.