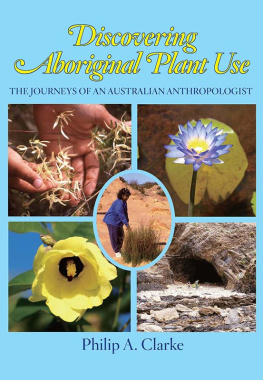

Discovering Aboriginal Plant Use

Journeys of an Australian Anthropologist

Silver cycad (Cycas calcicola). Tolmer Falls, NT 2010.

Discovering Aboriginal Plant Use

Journeys of an Australian Anthropologist

Philip A. Clarke

ROSENBERG

Dedication

To all ethnobotanists

First published in Australia in 2014

by Rosenberg Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 6125, Dural Delivery Centre NSW 2158

Phone: 61 2 9654 1502 Fax: 61 2 9654 1338

Email:

Web: www.rosenbergpub.com.au

Copyright Philip A. Clarke 2014, text and photographs.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher in writing.

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication data:

Author: Clarke, Philip A.

Title: | Discovering aboriginal plant use : the journeys of an Australian anthropologist / Philip A Clarke. |

ISBN: 9781925078220 (hardback) ISBN: 9781925078350 (Epdf) ISBN: 9781925078367 (Epub) |

Subjects: | Clarke, Philip A.

Human-plant relationshipsAustralia.

Aboriginal AustraliansEthnobotany.

Aboriginal AustraliansMedicine.

Aboriginal AustraliansFood.

Aboriginal AustraliansSocial life and customs. |

Dewey Number: 333.9530899915

Photographer: All photographs Philip A. Clarke 2014 unless otherwise credited.

Set in Warnock Pro 12 on 14 point

Printed in China by Everbest Printing Co Limited

Acknowledgments

The following people provided help with the writing of this book. The original idea of writing a book on plants in the form of a journal came from a discussion with Michael Madigan, whom I thank for his practical knowledge and experience with publishing. Kim Akerman, Elizabeth Grant and Leonard Cohen generously made time to provide detailed comments on drafts of the work. Cameron Clarke and Kyle Clarke assisted with plant photography. Ray Marchant drew the regional map of Australia. As background for the research material covered in this volume, many Aboriginal people have discussed with me their knowledge of the country for which they have custodianship over, as well as allowed many of the photographs within this current work to be taken. I thank them for their enthusiasm when talking about plants and for their patience, particularly when recording language terms. The Waterhouse Club at the South Australian Museum helped get me into the field on many occasions. Over the last thirty years, working as an anthropologist from the 1980s through to 2011 at the Museum, and since then in private practice, has given me many exciting opportunities to explore Aboriginal culture.

Contents

Introduction

There are many ways to explore a culture other than your own. Early on in my career as an anthropologist I choose to use ethnobotany as the window through which to better understand Aboriginal Australia. Ethnobotany is concerned with the relationships between human cultures and the floraa diverse field of study. In the past it was mainly used by European scholars to study hunter-gatherer societies and non-Western horticulturalists; today it is being used to study indigenous peoples and cultures in a postcolonial world. The current work offers insights garnered from my field journals over the last thirty years, showing how I have been able to conduct ethnobotanical research. It my argument that we can better understand a people if we know how they see and use plants.

In 1896, American botanist John W. Harshberger was the first to publish the term ethnobotany, by which he meant the study of plants used by indigenous peoples. The word is derived from Greek ethnos, referring to people, and botany, which concerns plants. Commercial interest in the plants used by indigenous peoples started much earlier than did academic interest. European documentation of Indigenous Australian plant use began with the land and sea explorations of the late eighteenth century and continued through the nineteenth century, driven primarily by the practical needs of finding new species of possible economic benefit to settlers.

In the twentieth century, Western scholars began to study the indigenous cultures of the world in their own right, and it was this different way of looking that led to ethnobotany being used to study the complex interrelationships between culture and flora. The backgrounds of todays ethnobotanists are diverse, with practitioners coming from such disciplines as botany, anthropology, linguistics, ecology, nutrition, medical science, social history, geography, archaeology and pharmacology. Such wide-ranging recruitment provides both strengths and weaknesses, with the specific interests of each recorder leading to particular specialities and biases in the compilation of data, and a variety of techniques being employed. With a background in both botany and anthropology, I also have adopted an eclectic set of intellectual tools.

My career with the South Australian Museum in Adelaide was diverse, and included managing collections, organising exhibitions, answering inquiries and conducting fieldwork. My public service role changed over the years during my transitions from museum assistant, to collection manager, curator and head of anthropology, but I managed to maintain my research interests in ethnobotany. From the mid-2000s, however, when the Museum was bureaucratised and directed to increase its public programs at the expense of research and collection maintenance, I found being actively involved with anthropological study and fieldwork ever more difficult. In late 2011 I resigned, leaving behind the tasks of approving timesheets and writing safe-operating procedures for office machinery for the far less certain but more exciting life of an anthropologist consultant. After being a public servant for much of my career, the opportunity to work more directly with Aboriginal communities on projects such as native title and land interest research was very attractive.

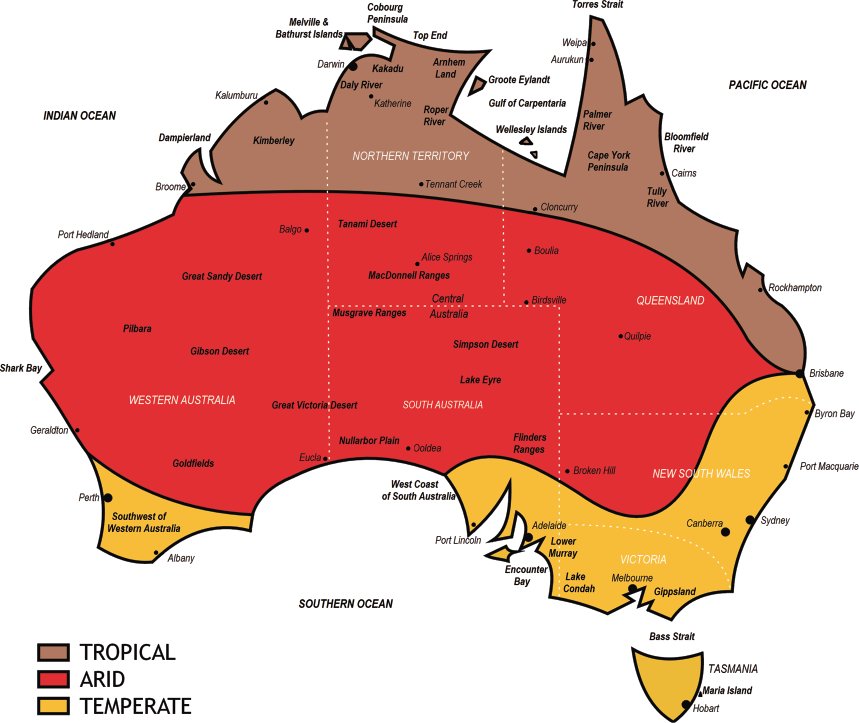

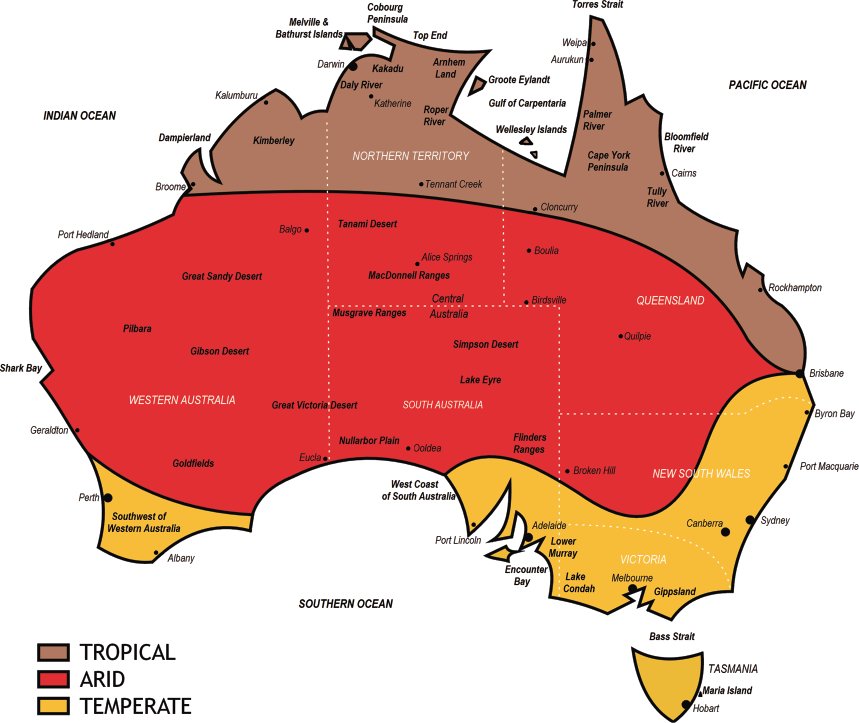

Australia is a geographically diverse continent, with three main climate zones. Drawn from climate data obtained from the Bureau of Meteorology, Australian Government, 2005.

In this present work I provide an outline of my journeys during more than thirty years as a biologist/anthropologist. My account is divided into three parts, covering the temperate, arid and tropical zones of Australia and neighbouring landmasses. Each chapter is focused on a fieldwork region, and begins with a summary of that regions cultural and natural heritage, and an outline of my reasons for being there. The bulk of each chapter is drawn from a journal account of my fieldwork, and each chapter finishes with detailed accounts of two plants that make the region distinctive in terms of its Aboriginal ethnobotany. The use of scientific plant names is avoided in the main text describing the journeys, in favour of colloquial terms used in Australian English. Terms from Aboriginal English, which is a distinctive variety of speaking used by Indigenous Australians, are also used as they add a contemporary aspect of Aboriginal relationships to the flora.

Part 1

SOUTHEASTERN AUSTRALIA

Chapter 1

Adelaide Plains

The cultural records of Aboriginal Australia are largely held in government-funded collecting institutions based in capital cities. From their beginnings in the mid-nineteenth century, Australian museums have actively acquired large collections of Aboriginal artefacts as a resource for both exhibitions and scholarly research. In the late twentieth century, other public institutions broadened their collecting brief to include Indigenous materials. Art galleries began acquiring contemporary Aboriginal art, such as Arnhem Land bark paintings and Western Desert-style canvases. Government-funded archives and libraries became more involved too, building large collections of manuscripts, books, sound recordings and images to cater for researchers studying Aboriginal history. While I would not go so far as to claim that these institutions have captured a comprehensive record of Indigenous Australian cultures, it can be said that a serious scholar could spend a whole lifetime trawling through what was already recorded without further fieldworkand in the case of Aboriginal plant use, the totality of existing records is immense (although there are significant gaps).

Next page