INTRODUCTION

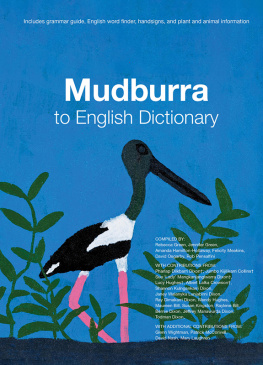

T here were, and still are, hundreds of different Aboriginal languages spoken on the Australian continent. Before the invasion which began in 1788, Aboriginal people did not belong to the single political unit such as Australia now is; they were divided into something like 700 different political groups which have traditionally been called tribes. There were approximately 250 different languages spoken on the Australian continent when Europeans first arrived on the shores. These languages are as rich and complex as any human language. Widely available wordlists such as Endacott (1924/1990) and Reed and Reed (1965/1974) help perpetuate erroneous beliefs about Australian languages by listing together words from various parts of the continent, and from very different languages. For instance, Endacott gives no information in his list as to which language the words come from, and Reed and Reed provide in places only some very general locational information whether the word is from Queensland, the Northern Territory, Central Australia, and so on.

Such books are of no greater value than a European wordlist which included words from all over Europe, but gave no indication of which languages the words came from. This series provides reliable information about words in various Australian languages, in a form that is accessible for the general public, while avoiding the pitfalls of the wordlists of Endacott and Reed. Words have not been selected (as in earlier wordlists) on the basis of sounding pleasant or being easy to pronounce for the English speaker, because this would give the false impression that Australian languages have only such euphonious words. Rather, they have been selected more to give some small inkling of the character of the languages.

NUMBER AND TYPES OF AUSTRALIAN INDIGENOUS LANGUAGES

The approximately 250 distinct Australian languages can be divided into around 26 different family-like groups, that is, groups of languages which are related to one another, and can most likely be traced back to a common ancestor language. One of these families covers about nine-tenths of the continent, the entire landmass except for the Kimberley and Arnhem Land.

This group of languages is referred to as the Pama-Nyungan family (named after words for man or person in many languages of Cape York and the south-west of Western Australia, pama and nyungar, respectively). The other families are also named, but they are frequently all grouped together and referred to as non-Pama-Nyungan languages. Non-Pama-Nyungan languages are similar to one another in a number of respects and different from Pama-Nyungan languages. Most of the wordlists in this series are from Pama-Nyungan languages, with Murrinh-Patha and Gooniyandi as examples of non-Pama-Nyungan languages. The languages spoken on various nearby inhabited islands including Groote Eylandt (Anindilyakwa), Bentinck Island (Kayardild), Mornington Island (Lardil), and Montgomery Island (Yawijibaya) are related to Australian languages. The same may also be true of the languages of Tasmania, but there is too little information on them to be sure, nor is it known for sure whether Tiwi, spoken on Melville Island is related to Australian languages.

Many, but not all, of the languages of the Torres Strait islands are related to Australian languages. Kala Lagaw Ya (spoken on Saibai Island) is an Australian language, but Meryam Mir (spoken on Murray Island) is not: it is a Papuan language, related to various languages spoken in Papua New Guinea. Since the arrival of Europeans in Australia just over 230 years ago, many significant changes have occurred. Most of the traditional languages are no longer used as the normal medium of communication among descendants of speakers of the languages; for many of these languages all that remains are the memories of a few words, or written or audiotaped recordings. (These records are the basis for several of the wordlists presented in this series.) Of the remaining languages, most are spoken by just a small (usually less than 100) number of adults, while children are not learning to speak them, but have switched to speaking some variety of English instead. There are only 14 really viable traditional Australian languages which are being used as the normal vehicle of communication within their community and are being used by the children.

These viable languages are all spoken in northern and central Australia. There are various reasons for the decline in use of Australian languages. In some cases whole communities of speakers were decimated, either by systematic killing by whites, or by introduced diseases (or both). Where such communities were not completely wiped out, they were reduced to such small sizes that they could not sustain their own identity or language, and were effectively absorbed into nearby groups. This seems to have been the fate of the Unggumi people, who lived around Windjana Gorge in the West Kimberley. In the late 19th century large numbers of them were massacred during the campaigns against the guerilla fighter Jandamarra (also known as Pigeon), who threatened white occupation of the region.

When the linguist Arthur Capell travelled through the area in 1939, he could find no more than a few descendants of the Unggumi and speakers of the language. They belonged to communities in which Bunuba and Ungarinyin speakers dominated the last fluent speaker of Unggumi died in 1993. Even in many northern areas with quite large Aboriginal populations, use of traditional languages has diminished. In many government settlements and missions children were separated from their parents once they had turned five or six, and were put into dormitories they were often only permitted to see their parents on weekends. The use of traditional languages was usually not permitted in dormitories, and children would be punished if they were heard speaking anything but English. In some places whole groups were forcibly moved from their traditional lands to reserves which may have been located a considerable distance away, sometimes in the country of traditional enemies.

The fractured communities that developed on reserves were not ideal places for the continued use and passing on of traditional languages. Where the use of traditional languages diminished they were normally replaced by some non-traditional, or post-contact language, although occasionally another traditional language acquired the status of a lingua franca, and was used as the main language of the community. Over large parts of northern Australia a simplified variety of English developed, initially from contact with whites, and came to be used more and more frequently among Aboriginal people. Such a language is referred to as pidgin. Sometimes a pidgin language becomes the mother tongue and primary language of the children, in the process becoming a full language called a creole. The pidgin English spoken in northern Australia creolised in many parts of the Northern Territory, Kimberley and Cape York, and the resulting creole is, in many areas, the main language spoken by Aboriginal people.

The creole spoken in the Northern Territory and Kimberley is referred to as Kriol. Kriol can probably be regarded as a single language spoken in a number of dialects. Torres Strait Creole, the creole spoken on Cape York and the Torres Strait islands, is a rather different language. Neither language is a dialect of English; both are distinct languages which speakers of English cannot understand without learning them. In the more populated southern areas, most Aboriginal people now speak Aboriginal English as their main language of everyday communication, often employing occasional words from the local traditional language. Aboriginal English is a dialect of English, which differs in certain respects from Standard Australian English.

There are, for example, some differences in vocabulary (some English words can have rather different meanings in Aboriginal English), grammar, and the norms of use (see Harkins 1994 for a readable account of Aboriginal English in Central Australia). Many Aboriginal people are concerned about the loss of traditional languages, and want to do something about it before it is too late. Language revival programs have been implemented in some southern areas, including a Kaurna language revival program in Adelaide. A variety of different types of language maintenance and bilingual education programs have been developed and implemented in parts of central and northern Australia, including bilingual education in Arrernte (at Yipirinya school in Alice Springs) and Yolu (at Yirrkala).