Published in 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016

Copyright 2017 by Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC

First Edition

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwisewithout the prior permission of the copyright owner. Request for permission should be addressed to Permissions, Cavendish Square Publishing, 243 5th Avenue, Suite 136, New York, NY 10016. Tel (877) 980-4450; fax (877) 980-4454.

Website: cavendishsq.com

This publication represents the opinions and views of the author based on his or her personal experience, knowledge, and research. The information in this book serves as a general guide only. The author and publisher have used their best efforts in preparing this book and disclaim liability rising directly or indirectly from the use and application of this book.

CPSIA Compliance Information: Batch #CW17CSQ

All websites were available and accurate when this book was sent to press.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Freedman, Jeri.

Title: Strategic inventions of the French Revolution / Jeri Freedman.

Description: New York : Cavendish Square, 2017. | Series: Tech in the Trenches | Includes index.

Identifiers: ISBN 9781502623478 (library bound) | ISBN 9781502623485 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: France--History--Revolution, 1789-1799--Juvenile literature. | Technological innovations--France--History--18th century. | Inventions--France--History--18th century. | Technological innovations--History--Juvenile literature.

Classification: LCC DC148.F74 2017 | DDC 944.04--dc23

Editorial Director: David McNamara

Editor: Kristen Susienka

Copy Editor: Nathan Heidelberger

Associate Art Director: Amy Greenan

Designer: Jessica Nevins

Production Assistant: Karol Szymczuk

Photo Researcher: J8 Media

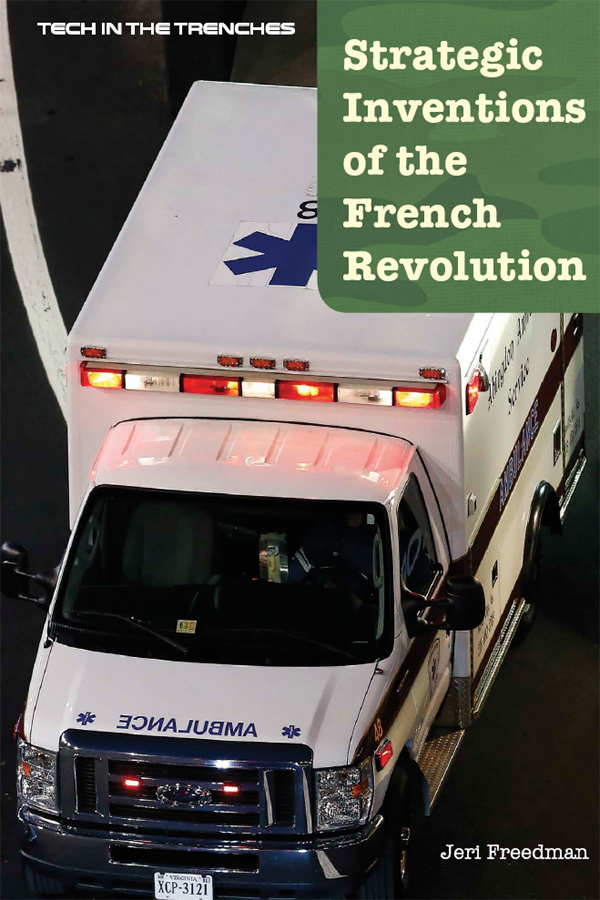

The photographs in this book are used by permission and through the courtesy of: Cover Tom Pennington/NASCAR/Getty Images; p. 4 Heritage Images/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; pp. 10-11 Horace Vernet/National Gallery/Wikimedia Commons/File: Valmy Battle painting.jpg/ Public Domain; pp. 14, 44, 56, 61 Apic/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 22 North Wind Picture Archives; p. 25 Leemage/Hulton Fine Art Collection/Getty Images; pp. 29, 100 Bettmann/Getty Images; p. 30 Jean-Baptiste Mauzaisse/File:Bataille de Fleurus 1794.JPG/Wikimedia Commons; pp. 36-37 Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin/ http://www.lib.utexas.edu /Wikimedia Commons/File: Western Europe 1700.jpg/Public Domain; p. 39 Carle Vernet/ http://www.sothebys.com/en/auctions/ecatalogue/2014/old-master-paintings-n09161/lot.92.html /Wikimedia Commons/File: An equestrian portrait of Napoleon with a battle beyond. jpg/Public Domain; p. 46 JLPC/Wikimedia Commons/File: Brouage 17 Canon XVIIe 2014.jpg/ Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 3.0 Unported; p. 51 Musee de lArmee, Paris, France/ Bridgeman Images; p. 55 Photo 12/Universal Images Group/Getty Images; p. 62 Mary Evans Picture Library/Alamy Stock Photo; p. 66 Culture Club/Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 70 Heritage Images/Hulton Fine Art Collection/Getty Images; p. 76 circle of Jean-Simon Berthelemy/ Nagel Auktionen http://www.auction.de/Wikimedia Commons/File:Jean-Simon Berthelemy (circle) Napoleon in the Battle of Maringo.jpg/Public Domain; p. 83 Unknown or not provided/U.S. National Archives and Records Administration/Wikimedia Commons/File: First Ambulance, 1865, US Navy Yard, Mare Island, CA - NARA - 296834.jpg/Public Domain; pp. 86, 93 Print Collector/ Hulton Archive/Getty Images; p. 88 Marina Lystseva/TASS/Newscom; p. 98 Museum of the City of New York/Byron Collection/Archive Photos/Getty Images; p. 100 Bettmann/Getty Images.

Printed in the United States of America

In the Enlightenment, scientists began conducting experiments to understand scientific principles. Here, a scientist named Le Monnier measures the speed at which electricity travels.

INTRODUCTION

An Enlightened Time for Invention

S cience and technology permeate every aspect of life today. The roots of much of that science and technology go back to the eighteenth century, often called the Age of Enlightenment. It was an era when science began to replace religion as the guiding principle of life. In the Enlightenment (1600s1789), everythingincluding centuries-long methods of government by royaltywas open to question. Philosophers and scientists began to seek scientific solutions to problems, including social problems. Scientists and engineers explored new technologies, such as electricity. New inventions were created. Optical lenses, interchangeable weapon parts, new forms of medical transportation to remove the injured from the battlefield, and the first instances of flightby hot-air balloonall changed the industrial and military landscape.

FRANCOS FOOTPRINTS OF INNOVATION

France in the eighteenth century was a political, cultural, and economic center in Europe. Visitors from around the world came to learn about the latest fashions, art, and science. Spending time in France was part of the Grand Tour that well-off young people took upon completing their education. The French language was the language of culture and commerce throughout the world, much as English is today. Given Frances prominence, it was natural that it would be a focal point for new technologiesnew ways of thinking.

The science of the eighteenth century built on and continued the inquiries begun by members of the Royal Academy of Sciences, chartered in 1660 by Louis XIV. The academy initially had twenty-one members. The members were supported financially by the French government so that they could devote themselves to the full-time study of science. Likewise, the government covered the cost of printing the results of their scientific investigations. The members met in the Royal Library, dedicating themselves to their research. By the 1700s, there were forty members of the academy, and each member had assistants and associates they were training. At this time, most major cities in France started their own academic societies, which promoted the study of science as well as other subjects. Lectures at these societies were often open to the public and helped popularize the idea that science could improve peoples lives. For example, it could provide information to improve agriculture and animal breeding, which would reduce famine and make food more readily available and less expensive. On the eve of the French Revolution, there were fifteen agricultural societies in France seeking to use science to improve the food supply.

RIVALS IN THE WORLD OF INVENTION

Inventions were being developed in every area of life and work at this time throughout the world. British, American, French, German, Italian, and Swiss inventors were all working out the principles and coming up with early models of many of the inventions that became commonplace in the nineteenth, twentieth, and twenty-first centuries. The scientists of the day were largely graduates of European universities. This was not necessarily true of the inventors. However, they were well educated in their own industry and technology, whether that was metallurgy and weapon making or surgery. Prior to the mid-eighteenth century, most skilled craftsmen received their training as apprentices, working for years for a master craftsman to learn their trade.