THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

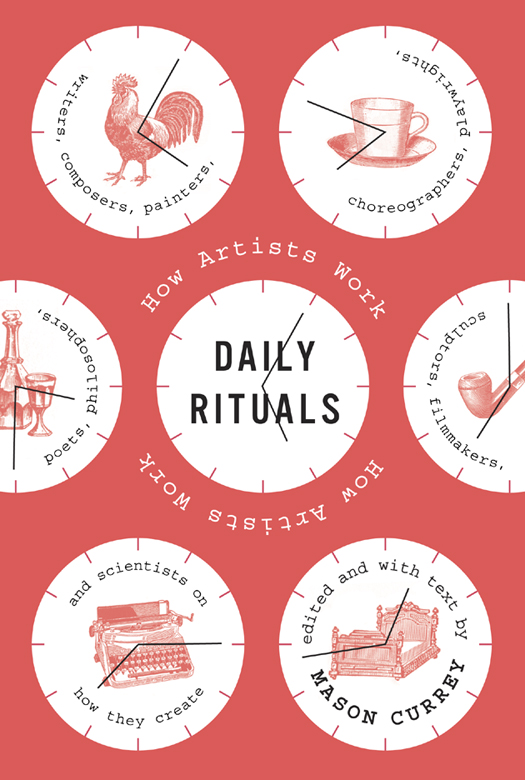

Copyright 2013 by Mason Currey

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada, Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

constitutes an extension of this page.

A brief essay is included herein by Oliver Sacks,

copyright 2013 by Oliver Sacks.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Currey, Mason.

Daily rituals: how artists work / by Mason Currey.First edition.

pages cm

eISBN: 978-0-307-96237-9

1. ArtistsPsychology. I. Currey, Mason. II. Title.

NX 165. C 87 2013 700.922dc23 2012036279

Jacket design by Jason Booher

v3.1

FOR REBECCA

Who can unravel the essence, the stamp of the artistic temperament! Who can grasp the deep, instinctual fusion of discipline and dissipation on which it rests!

T HOMAS M ANN , Death in Venice

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Nearly every weekday morning for a year and a half, I got up at 5:30, brushed my teeth, made a cup of coffee, and sat down to write about how some of the greatest minds of the past four hundred years approached this exact same taskthat is, how they made the time each day to do their best work, how they organized their schedules in order to be creative and productive. By writing about the admittedly mundane details of my subjects daily liveswhen they slept and ate and worked and worriedI hoped to provide a novel angle on their personalities and careers, to sketch entertaining, small-bore portraits of the artist as a creature of habit. Tell me what you eat, and I shall tell you what you are, the French gastronome Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin once wrote. I say, tell me what time you eat, and whether you take a nap afterward.

In that sense, this is a superficial book. Its about the circumstances of creative activity, not the product; it deals with manufacturing rather than meaning. But its also, inevitably, personal. (John Cheever thought that you couldnt even type a business letter without revealing something of your inner selfisnt that the truth?) My underlying concerns in the book are issues that I struggle with in my own life: How do you do meaningful creative work while also earning a living? Is it better to devote yourself wholly to a project or to set aside a small portion of each day? And when there doesnt seem to be enough time for all you hope to accomplish, must you give things up (sleep, income, a clean house), or can you learn to condense activities, to do more in less time, to work smarter, not harder, as my dad is always telling me? More broadly, are comfort and creativity incompatible, or is the opposite true: Is finding a basic level of daily comfort a prerequisite for sustained creative work?

I dont pretend to answer these questions in the following pagesprobably some of them cant be answered, or can be resolved only individually, in shaky personal compromisesbut I have tried to provide examples of how a variety of brilliant and successful people have confronted many of the same challenges. I wanted to show how grand creative visions translate to small daily increments; how ones working habits influence the work itself, and vice versa.

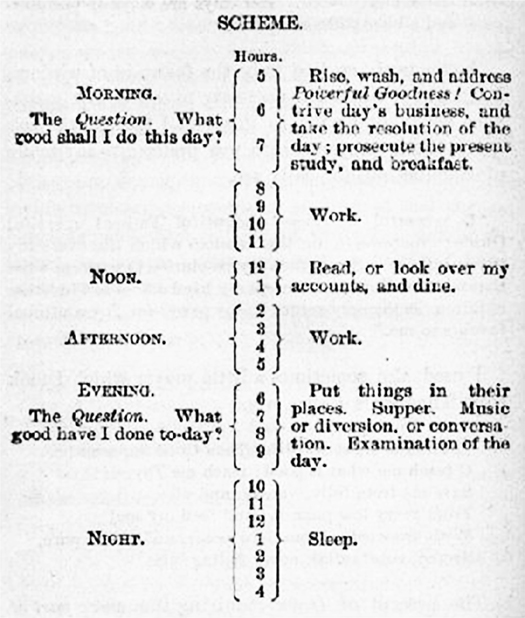

The books title is Daily Rituals, but my focus in writing it was really peoples routines. The word connotes ordinariness and even a lack of thought; to follow a routine is to be on autopilot. But ones daily routine is also a choice, or a whole series of choices. In the right hands, it can be a finely calibrated mechanism for taking advantage of a range of limited resources: time (the most limited resource of all) as well as willpower, self-discipline, optimism. A solid routine fosters a well-worn groove for ones mental energies and helps stave off the tyranny of moods. This was one of William Jamess favorite subjects. He thought you wanted to put part of your life on autopilot; by forming good habits, he said, we can ).

As it happens, it was an inspired bout of procrastination that led to the creation of this book. One Sunday afternoon in July 2007, I was sitting alone in the dusty offices of the small architecture magazine that I worked for, trying to write a story due the next day. But instead of buckling down and getting it over with, I was reading The New York Times online, compulsively tidying my cubicle, making Nespresso shots in the kitchenette, and generally wasting the day. It was a familiar predicament. Im a classic morning person, capable of considerable focus in the early hours but pretty much useless after lunch. That afternoon, to make myself feel better about this often inconvenient predilection (who wants to get up at 5:30 every day?), I started searching the Internet for information about other writers working schedules. These were easy to find, and highly entertaining. It occurred to me that someone should collect these anecdotes in one placehence the Daily Routines blog I launched that very afternoon (my magazine story got written in a last-minute panic the next morning) and, now, this book.

The blog was a casual affair; I merely posted descriptions of peoples routines as I ran across them in biographies, magazine profiles, newspaper obits, and the like. For the book, Ive pulled together a vastly expanded and better researched collection, while also trying to maintain the brevity and diversity of voices that made the original appealing. As much as possible, Ive let my subjects speak for themselves, in quotes from letters, diaries, and interviews. In other cases, I have cobbled together a summary of their routines from secondary sources. And when another writer has produced the perfect distillation of his subjects routine, I have quoted it at length rather than try to recast it myself. I should note here that this book would have been impossible without the research and writing of the hundreds of biographers, journalists, and scholars whose work I drew upon. I have documented all of my sources in the Notes section, which I hope will also serve as a guide to further reading.

Compiling these entries, I kept in mind a passage from a 1941 essay by V. S. Pritchett. Writing about Edward Gibbon, Pritchett takes note of the great English historians remarkable industryeven during his military service, Gibbon managed to find the time to continue his scholarly work, toting along Horace on the march and reading up on pagan and Christian theology in his tent. Sooner or later, Pritchett writes, the great men turn out to be all alike. They never stop working. They never lose a minute. It is very depressing.

What aspiring writer or artist has not felt this exact sentiment from time to time? Looking at the achievements of past greats is alternately inspiring and utterly discouraging. But Pritchett is also, of course, wrong. For every cheerfully industrious Gibbon who worked nonstop and seemed free of the self-doubt and crises of confidence that dog us mere mortals, there is a William James or a Franz Kafka, great minds who wasted time, waited vainly for inspiration to strike, experienced torturous blocks and dry spells, were racked by doubt and insecurity. In reality, most of the people in this book are somewhere in the middlecommitted to daily work but never entirely confident of their progress; always wary of the one off day that undoes the streak. All of them made the time to get their work done. But there is infinite variation in how they structured their lives to do so.