The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Like much of Charleston, I was at home preparing for bed when I saw my colleagues first tweets about a shooting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church. Just two months had passed since our newsroom at The Post and Courier fanned out to cover the shooting death of Walter Scott, an unarmed black motorist killed by a white police officer. When I saw that this latest violence occurred in an AME church, I called a minister in the denomination who had been a helpful source in the past. He was at a hotel near the church ministering to survivors and other church members. The man could barely speak.

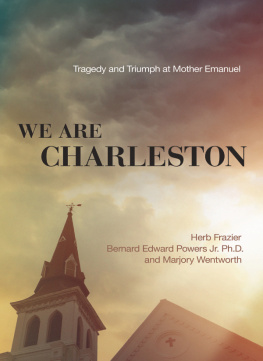

Mother Emanuels rich civil rights historyits revered status as the Souths oldest AME church, spiritual home to Denmark Vesey and his doomed slave rebellionframed my first story. It was a brief one, written on late deadline that night as the first victims name leaked out: Reverend Clementa Pinckney. A day later, I co-wrote the first detailed public account of what happened inside the fellowship hall, followed by dozens more stories over the coming months that allowed me to meet the survivors and many of the victims family members. Almost four years later, I feel like I know all nine who died through the memories of those who loved them most. I wish that Id gotten to meet them all.

I come from off, as the white locals here call it when they want you to know they belong to the storied soil of the place more than you ever will. In fact, I have lived in Charleston for two decades. My children attended school right across the street from Emanuel. I once was employed at the public library two doors down. For nearly all my time in Charleston, I have worked as a journalist at the citys daily newspaper. Before June 17, 2015, I had written a lot about the citys troubled racial legacy, but I had never experienced it as closely as I did while reporting on this tragedy.

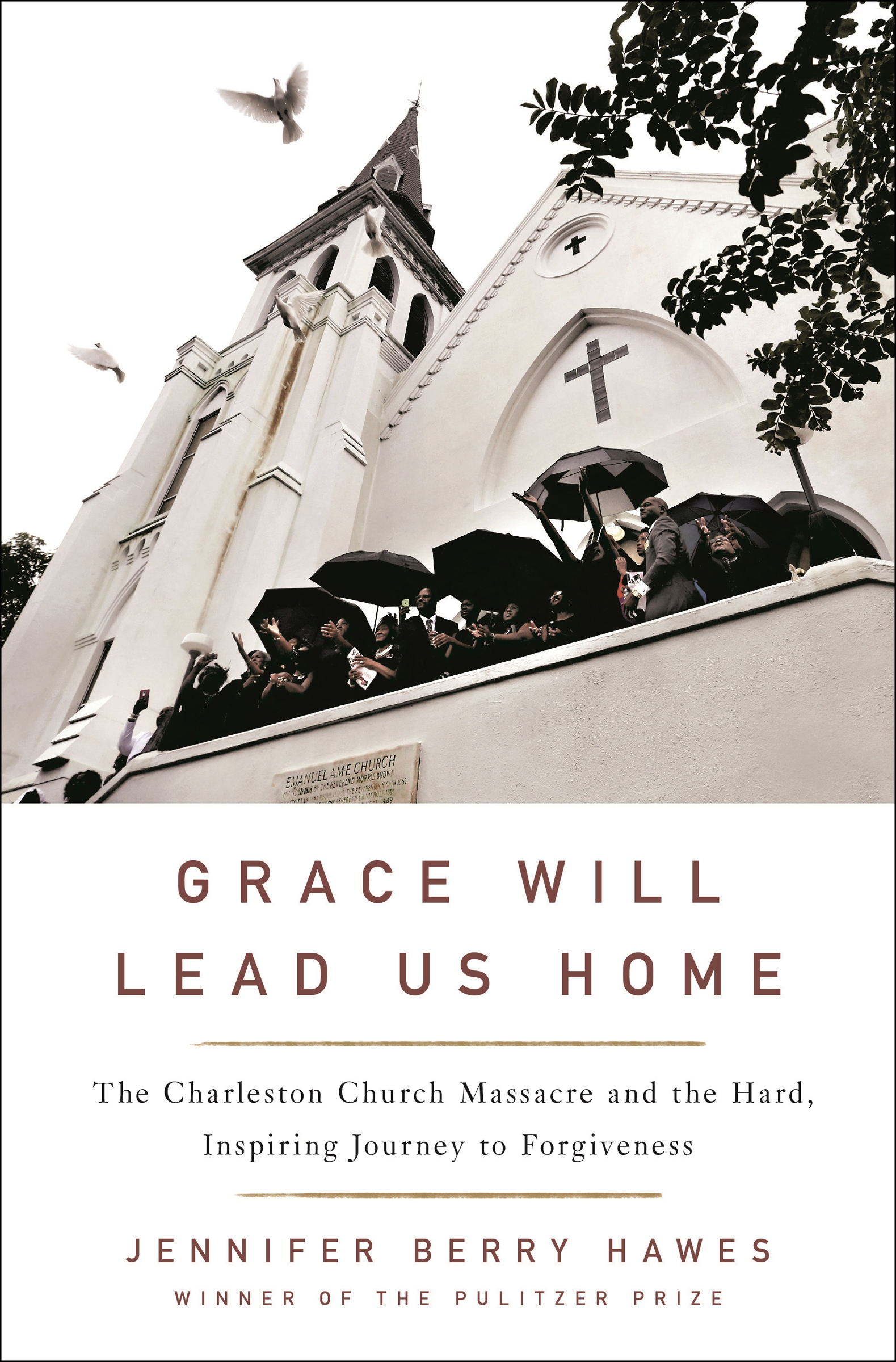

As a white woman, Ive since thought a lot about the difference between empathy and shared experience. While covering Dylann Roofs trial, most of the black journalists sat together in the media courtrooms jury box. Over coffee, one described for me the particular shared pain they felt covering this massacre. Hearing the killers racist rants and knowing he meant them for you and your family? I didnt experience his words the way that reporter did. But I could report and contextualize the roles of race, guns, and Christian faith in a state built upon the triumvirate of their influence. This is what I have attempted to do in the pages to come. I hope they provide a comprehensive picture of Charleston and the people who will live this story forever.

The adult survivors of this tragedy and many members of the victims families took considerable time to sit with me and help to tell this story. I hope they feel that I have remained faithful to their experience and sensitive to their suffering. I also want to acknowledge my debt to the reporters, editors, photographers, designers, management, and countless others at The Post and Courier. This book could not have been written without their insistence on bearing witness to the shooting and its aftermath, events that forever changed our city and the nation.

Jennifer Berry Hawes

It would be a late night. That much Felicia Sanders knew when she gathered her worn Bible and headed out into the swampy summer heat of June. She had a 5 oclock committee meeting at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal (AME) Church, where her family had worshipped since the days when Jim Crow ruled the old slave city she still called home. First, she would attend two meetings, one small and one large, to handle routine church business.

Last would come Bible study, her favorite.

She slipped into her black Toyota 4Runner, where she kept an extra pair of flats in case she was called to usher at the last minute. A day rarely went by that didnt bring Felicia to the place that many folks called Mother Emanuel, given its revered status as the Souths oldest AME church. Its members knew they could count on her to help with just about anything. Revivals. Mothers Day programs. Fundraising. Sunday school. Felicia, a fifty-seven-year-old grandmother and hairstylist, had served as a trustee, a steward, the usher board president. She even volunteered as Emanuels chicken fryer, although she herself was a vegetarian.

Felicia did it because she loved God, and she loved the congregation. Mother Emanuel was home.

A handsome woman with soft hips and high cheekbones, she had grown up with her siblings in Charlestons downtown projects, attending church with her strict grandmother after her own mother died young. Felicias husband, Tyrone, had also grown up among closely bound families in the working-class black neighborhoods near Emanuel. After years of hard work, however, they had been able to provide a suburban life for their own children, complete with a two-story house and the wide tree-draped front lawn that Felicia now drove past.

As she cruised along a winding road that led toward downtown Charleston, she wondered if her youngest child would make it to Emanuel that night. Tywanza also loved Bible study, but he was working a shift at Steak n Shake, one of his two jobs, and had warned her that he might run late. The thought meandered away as she crossed over a wide river, passed a marina adorned with gleaming white vessels, and merged onto downtown Charlestons thin peninsula.

Pedestrians crowded its thin streets, many lined with majestic old churches and finely restored antebellum homes. A few traffic lights stopped Felicia along a tourist-choked stretch of Calhoun Street, named after the countrys seventh vice president and one of its most ardent defenders of slavery. A 115-foot monument to the man towered over a verdant city square that bordered the street Felicia, a black woman, now navigated. It was so much a part of the place that she scarcely noticed it anymore. One building beyond the statue, she eased into a lot outside of Mother Emanuel and strolled inside, as she had thousands of times before.

As Felicia made her way into the church of her ancestors, a young white man, lean of frame, with a mop of bowl-cut sandy brown hair, sat one hundred miles away pecking at a keyboard inside his fathers house at the heel of a dead-end road. The young man sometimes slept overnight on the couch, although that wasnt his plan today. He was busy putting the finishing touches on his new website. Its subject: issues facing our race.

A couple of years earlier, hed Googled black on white crime, mostly out of passing curiosity, and stumbled onto a surprisingly robust realm of white supremacist websites. There hed discovered claims of grave threats to his racean epidemic of violence against whites, the overlooked inferiority of blacks, and a vast conspiracy to cover it all up. Writings on the sites hed plumbed after that search had fomented what he now considered his lifes great epiphany: his racial awakening.