THE SELECTED LETTERS OF

Anthony Hecht

THE SELECTED LETTERS OF

THE SELECTED LETTERS OF

Anthony HechtEdited with an introduction by

JONATHAN F. S. POST

2013 The Johns Hopkins University Press

All rights reserved. Published 2013

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

All letters by Anthony Hecht 2013 The estate of Anthony Hecht.

The Johns Hopkins University Press

2715 North Charles Street

Baltimore, Maryland 21218-4363

www.press.jhu.edu

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Hecht, Anthony, 19232004.

[Correspondence. Selections]

The selected letters of Anthony Hecht / edited with an introduction by Jonathan F. S. Post.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-4214-0730-2 (hdbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-4214-0785-2 (electronic) ISBN 1-4214-0730-2 (hdbk. : alk. paper) ISBN 1-4214-0785-X (electronic)

1. Hecht, Anthony, 19232004Correspondence. 2. Poets, American20th centuryCorrespondence. I. Post, Jonathan F. S., 1947 II. Title.

PS3558.E28Z48 2013

811.54dc23

[B] 2012012914

A catalog record for this book is available from the British Library.

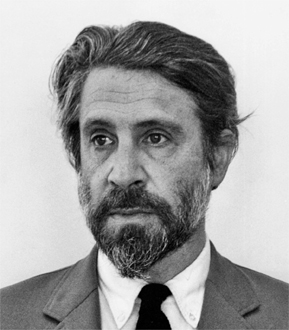

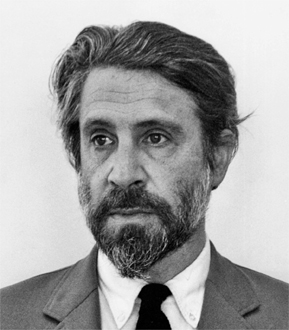

Frontispiece. Anthony Hecht, late 1960s, around the time that he received the Pulitzer Prize for The Hard Hours. (Courtesy of Helen Hecht)

Special discounts are available for bulk purchases of this book. For more information, please contact Special Sales at 410-516-6936 or specialsales@press.jhu.edu.

The Johns Hopkins University Press uses environmentally friendly book materials, including recycled text paper that is composed of at least 30 percent post-consumer waste, whenever possible.

ILLUSTRATIONS

Following

INTRODUCTION

IN ONE OF THE CHARACTERISTICALLY AMUSING OBSERVATIONS that makes reading his letters so enjoyable, Anthony Hecht remarked to his friend and English editor, the poet Jon Stallworthy:

It occurs to me that in the murky future, when it has been at length determined that I am a poet of sufficient interest to merit the publication of a volume of Selected Letters, the editor of that book will be at a loss to convey what may, in the last analysis, be the most sprightly, various, and original part of my correspondence: my letter paper. (December 22, 1976)

What is characteristic about the humor here is the note of self-deprecation in Hechts gradually, tellingly unfolding syntax. Initially imagining, with some small effort, a time in the murky future when his letters might be deemed worth collecting, the author manages to prick the puffery of this thoughtalthough not before nicely amplifying it with three well-chosen adjectiveswith the admission that the most valuable thing about his letters is the stock they are written on. How seriously are we meant to take the claim, we wonder? Not terribly. After all, Hecht only says what may be the case in the future. But the momentarily modest gesture has done its work. It disarms the passage of its potentially heavy freight involving posterity and lets us enjoy the airy possibility that his stationery is more valuable than his thinking, even as we smile over the sprightly claim that thought on paper has produced.

Hecht was speaking in this letter about nothing less than a duel to the finish with his friend and arch epistolary rival William MacDonald, the Roman architectural historian. The subject involved which of the two could come up with the rarest letterhead; and while MacDonald had an initial professional advantage, his work taking him to many distant lands, the more geographically circumscribed Hecht still had some tricks up his sleeve. He employed friends (spies as he calls them) to bring back stationery from all sorts of exotic and unusual places, even the White House. At one point, Hecht surmised that the most valued of all such heists would be the paper of the Warden of the Regina Coeli Prison in Rome (March 30, 1983). A Google search reveals that there is such a place and office, although I dont believe Hecht ever succeeded in this particular venture. But Hecht could be a persuasive fabricator of his whereabouts. So cleverly matched, in one instance, is the stationery from the Imperial Hotel in Japan with the description of a view of Mt. Fugi from the balcony in a letter written in 1979 that I had to check the biographical record to see if Hecht had ever returned to Japan after the time he spent there as a solder in the 1940s. He hadnt. And part of the joke, I quickly saw, was that the stationery itself had somehow survived as a relic from an earlier era. The Imperial Hotel had been torn down in 1968.

There is a great deal of this kind of mischievous fun in Hechts letters, which will not be surprising to readers of The Dover Bitch and The Ghost in the Martini, as well as much serious thought, as readers of Rites and Ceremonies and The Venetian Vespers might rightly expect. But his comment to Stallworthy also contains an important editorial truth. A published book of letters cannot perfectly represent the material conditions of their original epistolary circumstances. Whether as handwritten letters sent from camp or v-mails written from the military front or choice stationery bearing letterheads of the most elaborate and unusual orderoften artwork in itselfthe technology of book reproduction can only selectively hint at these visual features.

But equally to the point, we should remember (although the fact is often forgotten) that there is always a gap between the life and the faithful representation of that life that letters are assumed to convey. There is always a rhetorical context operating, even one as encompassing as a world war, and to read an authors letters only to arrive at a record of the selfhow devious that phrase is?performs a disservice of another kind. It is to miss the artfulness of letter writing, something Hecht seems to have understood instinctively. Or at least he came to understand it at a very early age, as the youthful letters written from summer camp suggest, with their penchant for reporting the odd detail or humorous event, in usually grammatically complete sentences, often in combination with a drawing or two to make the meaning graphically present. Hecht grew up in a cultured household on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, were reminded, where lettered expectations were the norm.

As one of the pre-eminent poets of his generation, the generation of poets who came of age immediately after World War IIa generation that includes his contemporaries and friends Richard Wilbur, James Merrill, and John HollanderHecht was not just a spirited but also a prolific correspondent. He took occasional days off, to be sure. The Fire Island summer sun, in particular, sapped his epistolary strength, and there are a few dark years from which no letters survive. But for the most part Hecht was a willing correspondent. He almost always replied to the many who sent him manuscripts or books to read, for instance, although his patience could be tested by those who gave no advance warning or by random inquiries that presumed on a sense of professional generosity. Such was the case of one Mr. Johnson, a lawyer, who sent a tome to Hecht in which he sought to disprove the assumption that the Stratford-born Shakespeare was the author of the plays, and received nearly a tome in return.

Next page

THE SELECTED LETTERS OF

THE SELECTED LETTERS OF