Hartnett - Wolf Creek

Here you can read online Hartnett - Wolf Creek full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2008, publisher: Currency Press, genre: Detective and thriller. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

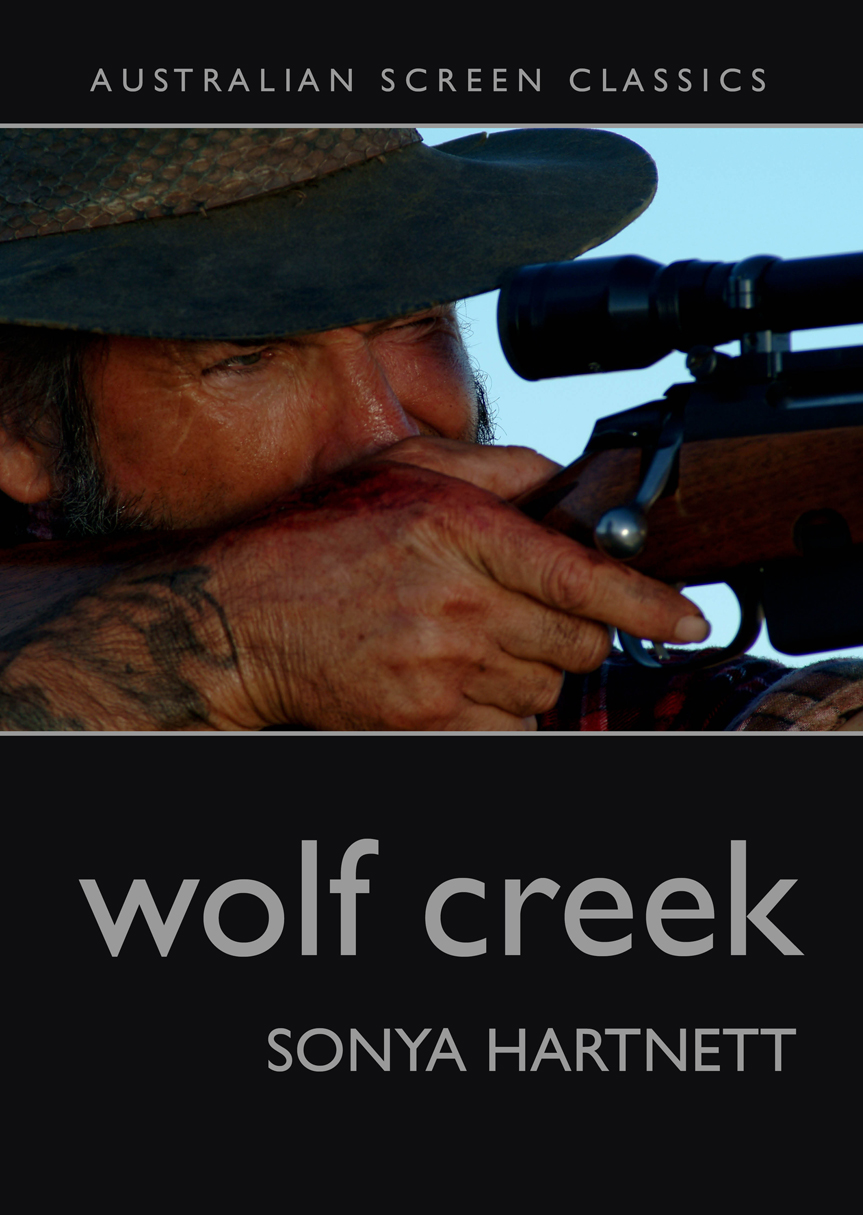

- Book:Wolf Creek

- Author:

- Publisher:Currency Press

- Genre:

- Year:2008

- Rating:5 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Wolf Creek: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Wolf Creek" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Hartnett: author's other books

Who wrote Wolf Creek? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.

Wolf Creek — read online for free the complete book (whole text) full work

Below is the text of the book, divided by pages. System saving the place of the last page read, allows you to conveniently read the book "Wolf Creek" online for free, without having to search again every time where you left off. Put a bookmark, and you can go to the page where you finished reading at any time.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

SONYA HARTNETT

Sonya Hartnett is the author of many novels for children, teenagers and adults, including The Midnight Zoo, The Ghosts Child and Of a Boy. She lives in Melbourne.

AUSTRALIAN

SCREEN CLASSICS

Jane Mills

Series Editor

Our national cinema plays a vital role in our cultural heritage and in showing us at least something of what it is to be Australian. But the picture can get blurred by unruly forces such as competing artistic aims, inconstant personal tastes, political vagaries, constantly changing priorities in screen education and training, technological innovation and the market.

When these forces remain unconnected, the result can be an artistically impoverished cinema and audiences who are disinclined to seek out and derive pleasure from a diverse range of films, including Australian ones.

This series is a part of screen culture which is the glue needed to stick these forces together. Its the plankton in the moving image food chain that feeds the imagination of our filmmakers and their audiences. Its what makes sense of the opinions, memories, responses, knowledge and exchange of ideas about film.

Above all, screen culture is informed by a love of cinema. And it has to be carefully nurtured if we are to understand and appreciate the aesthetic, moral, intellectual and sentient value of our national cinema.

Australian Screen Classics will match some of our best-loved films with some of our most distinguished writers and thinkers, drawn from the worlds of culture, criticism and politics. All we ask of our writers is that they feel passionate about the films they choose. Through these thoughtful, elegantly-written books, we hope that screen culture will work its sticky magic and introduce more audiences to Australian cinema.

Jane Mills is Associate Professor in Communication in the School of Communication and Creative Industries at Charles Sturt University. Her most recent book is Loving and Hating Hollywood: Reframing Global and Local Cinemas.

With thanks to Jenny-Lynn Potter and Dmetri Kakmi.

I

I first saw it when it came out at the cinema, but Id been thinking about Wolf Creek for years.

When I was eight years old my mother took my brothers and sisters and myself to a farm in Gippsland for a holiday. It was a working farm but, presumably to make some extra income, it took in tourists and stashed them in one of several on-site vans which stood in a clearing close to the farmhouse. I remember lying on my back on one of our vans thin mattresses, reading Enid Blyton and realising, as I did so, what books were for. They were for taking you away from wherever you were. The caravan-farm was a good place to leave.

We never had much money, and the holidays of my childhood werent grand. They never involved hotels or aeroplanes, but were passed close to the dirt in places my mother had driven to in one of various clapped-out vehicles. Almost always we left our father behind, backing the car down the drive in the earliest hours, not exactly escapingan early start made the most of the daybut leaving furtively enough to make it feel like escape. This time, however, my father followed us, turning up unannounced at the caravan door one afternoon. His presence was oppressive, just a twitch away from actually frightening. It only added to the atmosphere.

The farm was filthy. Not far from the caravans, a dead cow rocked on its bloated torso. Farm dogs rushed the strangers, their chains lashing the dust. The farmer, a loud man, encouraged the caravan children to chase the chickens. When one was finally cornered, the farmer put it on the block and chopped its head off. I can still hear the thock as the hatchet fell, still see the headless bird running. The farmer hadnt told us the game would end like that.

Walking the paddocks, my sisters were electrocuted crawling under a warningless fence. I remember their screams flying into the air and vanishing. I did not immediately understand what was happening to them. It seemed as if the land itself, where they touched it with their palms and knees, was tearing them to pieces inside.

I have never known a time or a place so steeped in wrongness as that farm. I lay day after ugly day on that mattress aware of my untrustworthy father, my seething mother, the hot air gusting, the dogs barking, the festering carcass, the squalling children, the metal walls of the caravan creaking with heat. I climbed the Faraway Tree with all the concentration I had.

There is a photograph taken by me from that timethe first photograph I ever took. To one side is my baby brother, but he is not the focus. Rather, my eye was on a pile of black pups which lay noodlishly entwined, asleep in the shade of a caravan. I was a child used to making the best of a situation. These pups, on that farm, were my sole good thing. And one day the farmer announced that that night there would be a fancy dress competition and that the winner would receive, as a prize, one of the pups.

We had not, of course, come prepared for such events, and had nothing from which to make costumes. I remember the distress that sang in me as the afternoon slithered by. I had no costume, I would not win; my mother was unmoved. She had five children and a difficult husband: she did not want a pup. She never seemed to understand that, because there were five children and a difficult husband, a pup was what I craved. I struggled to piece together an outfit that would impress the farmer while going unnoticed by my mother, but in our pillowcases of clothes there were no ribbons, no paint, no high-heeled shoes. I cobbled together a pathetic something but I knew I wouldnt win. I knew conditions were such that I was neither destined nor permitted to win. Nonetheless I remember stepping out with that hopefulness to which a child can cling even in the face of absolute defeat. Maybe somehow, miraculously, the entire world would change.

I dont think the farmer looked twice at me. The rabble of caravan children were arranged in a circle around the bonfire and the farmer walked the perimeter, the pup in his arms. When he came to me, I looked at the pup. I recognised it. I wanted to win. But it was not my hair which was ruffled by a rough hand, not my face which was raised to a skeleton-rattle of applause. When the farmer hoisted the pup by the scruff, it wasnt my name he called. I didnt get the dog: yet on that night, something did change.

I was wearing an outfit of rags, surrounded by children dressed likewise. The sky was unbrokenly black. The flames of a pyre-like bonfire kicked and swiped at the night. Its heat lit our faces in strange ways. There was music coming from a tinny cassette player, and dogs were ceaselessly barking. The smell was of smoke and meat. The farmer stood like a ringmaster, shouting, hotly enjoying each moment. He was in command. This world was hishe knew it, he owned it, it lived and died as he desired. The terrible dogs would jump to his word. He had brought us here, told us how we must behave. The fire was his, hed built it, he could consign anything he wished to the flames. We children were staring to him, all our eager unsure faces, intent upon his every word. Our faith and our dreams lay with him. He raised the pup like a sacrifice to the moon; dogs howled, the air stunk, stinging sparks blew. The adults laughed and grimaced, even my own fearsome father small before him. For minute after minute it was mesmerising: Id never forget the cartwheeling feeling of derangement, how the earth and the animals and the elements seemed to conspire with the dust-covered man to humble and mock and render helpless his audience who were not, as he jocularly pretended, his friends, but his hated audience, his prey. It would be years before Id recognise what I was seeing, how the fire, the darkness, the burned dirt, the baying hounds were all characters playing, pitch-perfectly, their role; years before I realised that the poverty, filth and fear were vital, the stage incompletely set without them. Yet some awareness did sink through me even as I stood in my failure of a costume, weeping the loss of a dog I never owned. This red-stained diorama, this small nightmare, this rank carnival of wretchedness spoke to me. It told me there was power and weakness in the world, sanity that masked insanity, kindness which concealed rage. It was no ground-breaking discovery, yet it felt like finding a key. Understanding was like the donning of armour.

Font size:

Interval:

Bookmark:

Similar books «Wolf Creek»

Look at similar books to Wolf Creek. We have selected literature similar in name and meaning in the hope of providing readers with more options to find new, interesting, not yet read works.

Discussion, reviews of the book Wolf Creek and just readers' own opinions. Leave your comments, write what you think about the work, its meaning or the main characters. Specify what exactly you liked and what you didn't like, and why you think so.