This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Epub ISBN: 9781409019671

Version 1.0

www.randomhouse.co.uk

Published by Yellow Jersey Press 2011

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Copyright Leo McKinstry 2011

Leo McKinstry has asserted his right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 to be identified as the author of this work

First published in Great Britain in 2011 by

Yellow Jersey Press

Random House, 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road,

London SW 1 V 2 SA

www.rbooks.co.uk

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at: www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780224083294

www.vintage-books.co.uk

About the Author

Leo McKinstry writes regularly for the Daily Express, the Daily Mail and the Spectator. He has written nine books, including a life of Geoff Boycott, which was named one of the finest ever cricket books in a recent Wisden poll. His biography of Jack and Bobby Charlton was a top-ten bestseller and won the WH Smith Sports Book of the Year award. His biography of Alf Ramsay won the WH Smith Football Book of the Year award. His study of the Liberal Prime Minister Lord Rosebery won Channel Four Political Book of the Year. His most recent books are a trilogy about the RAF in the Second World War.

Born in Belfast in 1962, he was educated in the west of Ireland and at Cambridge University. He is married and lives in Kent and Provence.

About the Book

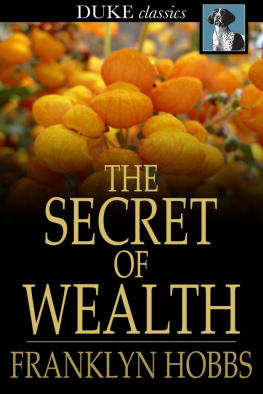

The astonishing feats of Sir Jack Hobbs continue to resonate more than a century after he first played Test cricket. During his long career that stretched from the age of W.G. Grace to the era of Don Bradman, he scored more first-class runs and centuries than any other player. Even today, he remains Englands greatest run-maker in Ashes Tests. He changed the art of batting with his elegant style, and transformed the status of professional cricketers through the strength of his quiet, dignified personality.

Despite his significance in the game, there has never been a comprehensive biography of Hobbs. Now Leo McKinstry, the acclaimed author of a best-selling life of Geoff Boycott, has remedied that. Based on a wealth of new material, including interviews with the Hobbs family, the book provides fresh insights into every aspect of his story, from his poverty-stricken upbringing in Cambridge to his central role in some of Test crickets most explosive series.

It is a tale full of controversy, such as the previously unknown row over his actions in the First World War, when he was accused of scandalous behaviour by the cricket establishment. Other dramatic episodes include a bitter dispute over the England captaincy in the 1920s, as well as two occasions when he came close to death. With its colourful detail, historical context and readable style, this ground-breaking book is an important addition to sports literature.

Epilogue

WHEN JACK HOBBS was growing up in late-Victorian Cambridge, many professional cricketers faced a dismal retirement. Low pay, lack of pensions and chronic job insecurity meant they struggled to provide for their old age. Even benefits for the long-serving stalwarts were subject to the whims of weather and committees. In 1901, the year that Hobbs first played minor counties cricket, the famous Nottinghamshire fast bowler John Jackson died in a Liverpool workhouse as a pauper, his estate valued at fifteen pounds. Similarly the popular Surrey wicketkeeper Ted Pooley, having worked after his playing days on a building site, spent the last nine years of his life in a Lambeth workhouse before his death in 1907. It was the workhouse, sir, or the river, he said to one writer who had been moved by his plight. But the vast improvement in the status of professionals, as well as the creation and expansion of the welfare state, meant that cricketers of the 1930s faced nothing like this penury. Those at the top, such as Hobbs, Woolley and Hendren, could be described as successful members of the upper middle-class, with substantial homes, cars, income and investments.

Hobbss retirement in 1935 certainly did not involve the prospect of any financial constraints. He was now a man of means, the harsh early days of Rivar Place far behind him. He still had plenty of well-paid work through his journalism, though it must be said that his position in the press box owed more to the lustre of his name rather than the incisiveness of his ghostwritten prose. In his penultimate season of 1933, the Star gave him a weekly column on cricket. Initially, Jack Ingham acted as his ghostwriter but from 1935 the role was taken over by the sports journalist Jimmy Bolton. Together, they travelled out to Australia for the 1936/7 series, his last trip there for an Ashes series. Hobbs also had a quartet of lucrative books published under his name in the 1930s. Two of them were essentially just compilations of his press reports on the 1932/3 and 1934 Ashes series, but more interesting were his pair of autobiographies. The first, Playing for England, covered his entire Test career and was written by the versatile journalist, author and poet Thomas Moult, a close friend of Neville Cardus. The book had the occasional striking passage but was devoid of revelations and did not match the quality of Inghams 1924 volume for Hobbs, My Cricket Memories. The weakest, however, was My Life Story, written by Bolton and published in 1935. Much of the text was just lifted from the previous two books, while key dramatic incidents, like the Bodyline series or the 1926 Oval Test, were dealt with in a perfunctory manner. To be fair, the problem for all Hobbss ghosts was the essential decency of his character, which meant that he both hated to criticise others and shrank from anything he perceived as boasting. As Gordon Ross, the historian of Surrey, once put it, Rarely can you get him to talk about himself. Unlike hard-nosed reporters whose lifeblood was controversy, Hobbs shied away from it, as shown by this comment in November 1936 about an umpiring dispute in the Ashes series: The press box is not a good position from which to judge a leg-before decision but I know that umpires are only human beings and are liable to make mistakes, although they are in the best position to see. This was hardly the kind of material to set an editors pulse racing. The other problem for his cricket writing was that, because the game came so naturally to him, he was not the most perceptive analyst of techniques. On one occasion the Essex amateur Leonard Crawley came off the field after witnessing another of Hobbss superlative innings. I would love to ask him how he does it, but I know he wouldnt be able to tell me, he said to a teammate.

Hobbss earnings from his books and articles were augmented by the success of his Fleet Street shop, where he worked at least three days a week in his retirement if he did not have other commitments. All this maintained a comfortable life for his family, and throughout his later years he exuded an air of prosperity. He dressed quietly but fastidiously: dark grey suits; white shirts; a Surrey or England tie; well (self-) polished shoes, wrote John Arlott. He liked driving and, over the years, owned a series of solid British saloons. No longer burdened by the demands of top-class cricket, he gave up his teetotalism and allowed himself to enjoy wine, champagne and the occasional liqueur, as well as cigars.