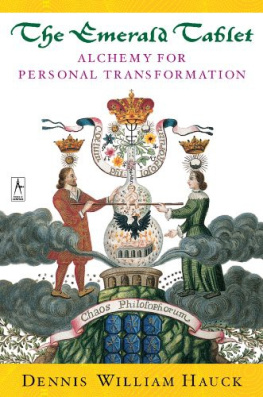

The alchemical operation consisted essentially in separating the prima materia, the so-called chaos, into the active principle, the soul, and the passive principle, the body, which were then reunited in personified form in the coniunnctio or chemical wedding.

C. G. Jung, Alchemical Studies

T he risk in exposing our sources of inspiration, where the primal spark comes from and how it is transmuted, is of tearing the wings from a butterfly to explain flight. The impulse to write, to put a shape on chaos, is the neurosis that defines us, that allows us to find credit in failure: poetry as a sickness vocation. But then, as the various contributors to the collection published as Alchemy discover, there is relief in that provocative metaphor. Alchemy, existing on the hinge of the medieval and pre-modern worlds, offers a certain dignity of process to initiates of language; the branded ones who are prepared to work and rework, in darkness, by instinct, to achieve the faintest sliver of golden light. It slips through their fingers like a mercury spill. The story. The innocent confession. The lie that persuades. The comforting illusion of achievement in the accidental arrangement of words on a page.

The Alchemy writers identify with an intensely local force field known as the Self, while appreciating that its borders, through homeopathic doses of loss or hurt or love, can burst; so that, in the instant of composition, there is no division between individual consciousness and the world at large. Vision is the name we give to that absolute. The thing that cant be forced, prostituted or sold short. And herein lies the paradox and the challenge for the five chosen witnesses, who are privileged to write themselves out of the trap, the Faustian contract, by way of personal anecdote, strategic revelation or hopeful punt in the dark. The belief is declared several times in these essays that the natural world has its established mechanisms, suns will rise and rise again. We labour in that expectation, blackest night before dawn. Disillusion, anomie, betrayal are accepted as necessary tolls for access to the Great Work.

Gabriel Josipovici quotes Beckett, somebody had to: Bon qua a. The condemned author condemned to live puts words on paper because it is all that he or she can do. Foolish to comment any further. But now comment is required. Comment has been solicited. The writing is painfully aware, Josipovici says, of the fact that the rhetoric both reinforces and undermines the anguish.

In playing the game, feinting at a posthumous explanation for what is, in effect, an electrochemical seizure, a sudden thickening of the tongue, a suspension of conditioned reflexes, the essayist finds relief in identification with terrain, some elective topography capable of bearing the weight of the metaphor that must be imposed upon it. Vision is out there and we will walk, hobble, swim or crawl, to find it. The special place might, for Partou Zia, be a flint field at the end of the land. A soft-focus garden running down to the Thames for Joanna Kavenna. A busy urban road for Gabriel Josipovici. An aircraft coming down on a motorway embankment for Anakana Schofield. Geography is destiny, but reality is a tight bone cage: the cell of the skull from which consoling sets are conjured. The writers task is to recognise the place that is writing you; triggering the voices, giving you permission to continue.

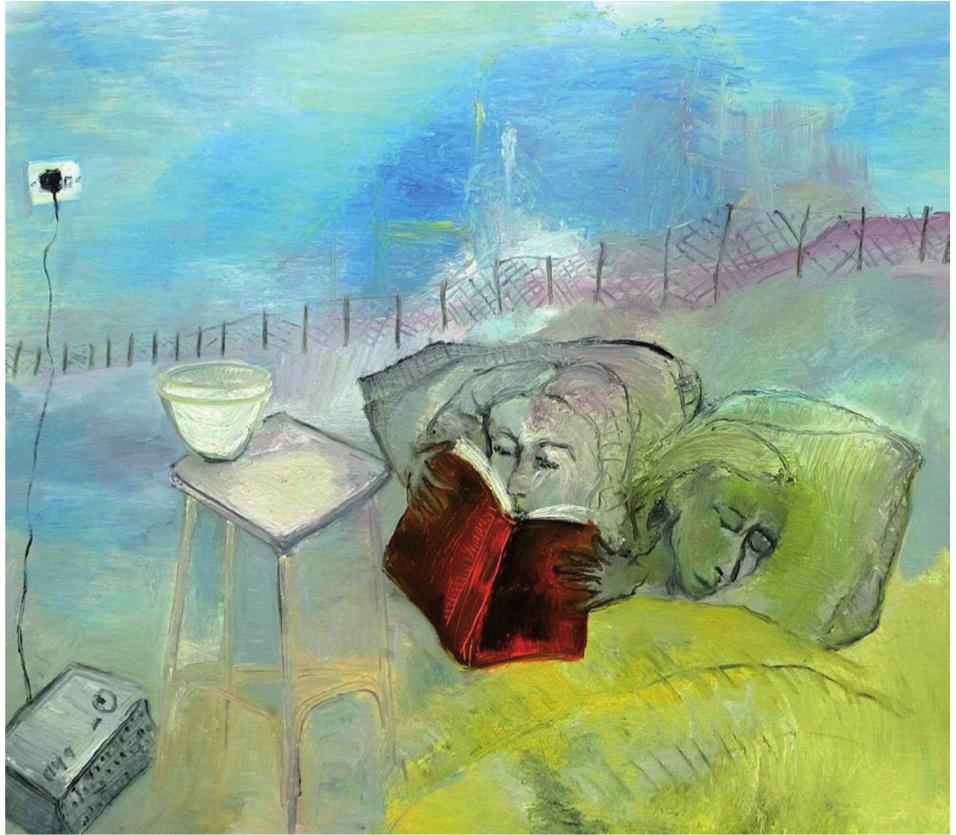

I began my own long and frustrating engagement with London by quoting from A Vision by W. B. Yeats. And Ive never, in more than forty years, found good reason to go beyond that. The living can assist the imagination of the dead. We are ventriloquised, confirmed in our fantasies. This is what we must do and we are doing it. To drift into the poetic is in itself work, Zia says. Kavenna shares my belief that writing is rewriting. We receive and record the stories that press in upon us, across the boundaries of sleep and mortality. I was troubled by bad dreams and these had an intensely tactile and auditory quality, and often seeped into the ensuing day, like a miasma. In my dreams the dead were alive. It is not Kavenna talking to us, it is her character, her creature, Anthony Yorke, who is one thing here and another in a different text. He is a blocked writer, a teacher and an actor. He luxuriates in taxonomies of failure. He resents his role in this slippery production. This is nothing and everything, all at once.

With intimations of a double displacement, separation from homeland and from physical well-being, Zia recognises her exile as a highway. Barren country roads crowned by a ribbon of mathematically-arranged wires that stitch earth-horizons with the wide sky. Hours spent in bed reading, my only solace. Outside is alien, and I am too vulnerable to venture forth. The cold English sea is a cinema of memory in which the memories are not her own. The road is a prediction, running from past to future. There are those who will scowl at the pavement as they tread their isolated path, determined to keep their starved souls in the deprived element of spiritual poverty. Along the stripped spine of a moorland track, the unresting dead are the only pilgrims.

What excites me, as a reader of the five texts, is how molecular reactions fizz between them to stitch a single hydra-headed, argumentative entity. It really does feel that none of these pieces could have been written in the form they have settled on without the existence of the others. Sometimes the forward momentum of the narrative is grudging, sometimes it flows with the reckless inevitability of a river in spate. Zias road of exile, out there in the far west, tapping sources common to earlier migrants, such as W. S. Graham, D. H. Lawrence, Mary Butts, dissolves into Josipovicis tramp from Brixton to New Cross: so endless, so rundown and desperate that it becomes purgatorial. Moral exhaustion opens a grunge portal on the horrors of Francis Bacons painting of a vomiting man in a sealed room. The description brought me back to my first experience of London in 1962, when I made a number of hikes from Electric Avenue, Brixton, to the great Bacon retrospective at the old Tate Gallery on Millbank. Prominence in the show was given to Bacons reworking of Van Goghs Painter on the Road to Tarascon; a molten rendering that became the marker for a lifetime of burdened trudging, of too many days walking out to write.

The condition of exile or tolerated otherness, defined by two of the Alchemy authors as a road, becomes an apprenticeship in migration for Benjamin Markovits. He leaves the USA for a season, trying out as a basketball player in Germany. Reading his finessed report, with its deceptively conversational style, we soon understand that the real apprenticeship, the bullet that cant be dodged, is to become a professional writer.