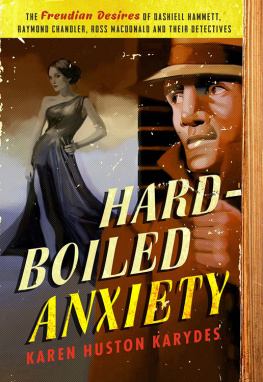

Hard-Boiled Anxiety

The Freudian Desires of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Ross Macdonald, and Their Detectives

Karen Huston Karydes

Hard-Boiled Anxiety: The Freudian Desires of Dashiell Hammett, Raymond Chandler, Ross Macdonald, and Their Detectives

Copyright 2016 by Karen Huston Karydes

All Rights Reserved

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwisewithout prior written permission from the publisher, except for the use of brief quotations for purposes of review.

For permissions, see .

For information about this title, contact the publisher:

Secant Publishing

615 N. Pinehurst Ave.

Salisbury MD 21801

www.secantpublishing.com

Library of Congress Control Number: 2014958598

ISBN: 978-0-9909380-6-4

EISBN: 978-1-944962-00-5

Cover Design: the Book Designers

Illustration: Scott Erwert

for Benjamin,

Nathaniel, Alexander,

and Thaddeus

and for Lewis Dabney,

who taught me how to write a book

Permissions

Excerpts

Hammett, Jo. Dashiell Hammett: A Daughter Remembers by Jo Hammett. Edited by Richard Layman. New York: Carroll & Graf, 2001. Courtesy of Jo Hammett and Richard Layman.

THE LONG EMBRACE: RAYMOND CHANDLER AND THE WOMAN HE LOVED by Judith Freeman, copyright 2007 by Judith Freeman. Used by permission of Pantheon Books, an imprint of the Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group, a division of Penguin Random House LLC. All rights reserved.

Reprinted with the permission of Scribner, a Division of Simon & Schuster, Inc., from ROSS MACDONALD: A BIOGRAPHY by Tom Nolan, 1999. All rights reserved.

The Kenneth Millar Papers. MS-L001. Special Collections and Archives, The UC Irvine Libraries, Irvine, California; and used with the permission of Norman Colavincenzo, Literary Executor of the Estate of Kenneth Millar and Trustee of the Margaret Millar Charitable Trust.

Photographs

Contents

O n a February weeknight in 1956, in Santa Barbara, California, Linda Millar, sixteen and already chronically sad, sat alone in her car and steadily drank nearly two quarts of wine. Then she started driving. She ran through three thirteen-year-old boys walking home from a basketball game at their middle school, Our Lady of Guadalupe. Two of the boys were thrown seventy feet: one of them died and the other was maimed. Linda didnt stop. Ten minutes later she plowed into a parked car with its lights on and a couple inside. That vehicle was thrown sixty feet, and Lindas car rolled over. When she was detained, she lied; it took her forty-eight hours to admit to both accidents. A month afterward, she slashed her wrists and was hospitalized. Ken Millar (pronounced Miller), her father, was undone.

Millar, using the pseudonym Ross Macdonald, wrote popular detective novels, six with Lew Archer as the detective by 1956. Now he would write something very different. Notes of a Son and Father is an unpublished, confessional, harrowing account of Macdonalds childhood, marriage, and fatherhood. It can be found among the Kenneth and Margaret Millar Papers in the Special Collections and Archives at the University of California at Irvine Libraries. It looks unassuming: a dime-store spiral notebook with thirty-seven unnumbered pages of small, tightly penciled handwriting. Without doubt, it was an anguished exercise in courage both for Macdonald to write and then to give over to researchers who happen across it. It is a keystone of sorts for this book.

Macdonald began writing Notes of a Son and Father for Lindas psychiatrist in order to provide enough to give a line, at least a line to read between. he said. As he worked, he found the process of writing Notes of a Son and Father was an accounting of his own life, helpful for his own sake. On every page, Macdonald judges himself guilty of not loving his mother, father, wife, or daughter enough. The reader sees differently: Macdonalds father was unavailable to his son for years at a time; his mother was a hysteric; and his wife was angry. Macdonalda successful academic and writer, an effortful husband and fathersurely loved all of them enough.

Macdonalds childhood was full of predatory secrets and sexual shame. As soon as he couldand by 1936 both his parents had diedMacdonald reinvented himself. He triumphed in this willed performance for twenty years and then his daughter killed a thirteen-year-old boy. So Macdonald wrote Notes of a Son and Father and then tried adapting that experience to create openly self-realizing fiction, and the adventure of doing that made him a less-haunted, more present man. He finally could write about his past in the guise of Freudian fables within the structure of the hard-boiled genre. These later books, and particularly the best onesThe Galton Case, The Chill, and The Underground Mangot Macdonald to the far side of pain, to a place where he could make the best of the rest of his life. He changed. His detective changed. As Macdonald would say: Solve is the wrong word. Lets say understand.

The twelve Lew Archer books written after 1956 extend the work begun by Dashiell Hammett, who invented hard-boiled detective fiction, and Raymond Chandler, who gave it romantic voice. Macdonalds contribution was to see that the genre has conventions that can support any number of themesyes, even Freudian fables. He also had an inchoate theory that a culture has to have a popular fiction in order to grow an elevated literature, and thats what Hammett, Chandler, and Macdonald did: they turned their work in the hardboiled, pulp genre into exceptional literature.

Macdonald correctly argues that Dashiell Hammetts work showcases the direct meeting of art and contemporary actuality and begins to find a language and a shape for that experience. Hammett makes clear the second city, where the secret meanings of the factual world are. He does more than select telling details about San Francisco in 1929; he distills its rank perfume, using its cockeyed vocabulary and inventing the lonely, near-tragic

little man going forward day after day through mud and blood and death and deceitas callous and brutal and cynical as necessary towards a dim goal, with nothing to push or pull him towards it except hes been hired to reach it.

Hammetts little man is the Continental Op, the first hard-boiled narrating hero. He sprang from the reports Hammett filed as a Pinkerton National Detective Agency operative. From the Op forward, the hard-boiled private eye has been fashioned anomalously in his creators image, which makes knowing that authors biography all the more crucial to understanding his fiction. In Self-Portrait: Ceaselessly into the Past, Macdonald encourages us to coordinate the work with the life:

Hammetts coming of agehis Pinkerton work, tuberculosis, marriage, daughters (and a paternity question that arose in 1980, nineteen years after Hammetts death), and his long affair with Lillian Hellmanprovided the parts at hand that he used to assemble a code for both his fictional protagonists and his own behavior. The code was existentialist, honorable, atheistic, and unexplained; and it worked for the lot of themauthor and shamusesbut not in a sustained way because it did not address the anxieties that fueled Hammetts capacity for self-destructive behavior. Readers of his novels learn more about Hammett than he ever would have wanted known. They reveal what he and his detective heroes wouldnt discuss, matters especially taken up in