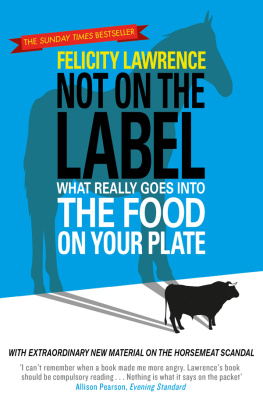

Felicity Lawrence is an award-winning journalist and editor who began writing about food-related issues nearly thirty years ago. Not On the Label won the Guild of Food Writers Jeremy Round Award for best first book in 2005 and a special commendation in the Andre Simon Awards 2004. Lawrence has twice been awarded the Derek Cooper Award for Investigative Food Writer of the Year, has twice been shortlisted for Specialist Reporter of the Year in the British Press Awards, and has been commended in the Paul Foot and Martha Gellhorn prizes. She is special correspondent for the Guardian and lives in London.

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published 2004

Revised edition 2013

Copyright Felicity Lawrence, 2004, 2013

The moral right of the author has been asserted

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-0-141-90716-1

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

PENGUIN BOOKS

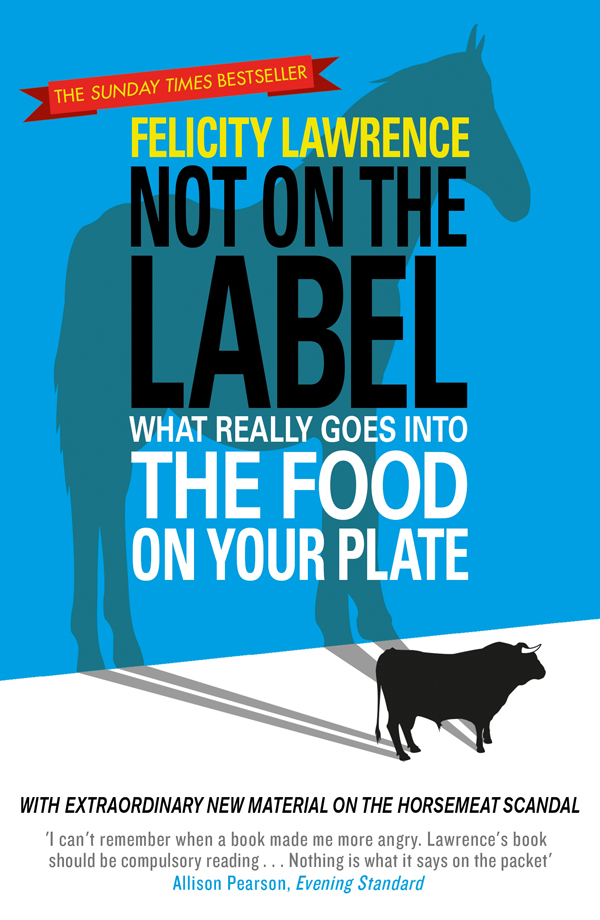

NOT ON THE LABEL

A stark, challenging and compelling book Sunday Times

Felicity Lawrences horrifying account of how the food we eat is produced doesnt make for a good nights sleep but is compulsively readable. It is the sort of book that changes attitudes Peter Parker, Evening Standard

From chickens in Devon to salad in Spain and beans in Kenya, Felicity Lawrence blends sleuthing and science with appetite-killing flair. Her expos of the costs of our year-round food cornucopia leaves no packet unscanned, and very few undamned Independent

A blistering expos of the global food industry, focusing on the role supermarkets play in deciding what we eat and how it gets to us. This is a great book that anyone who eats should read. It is also a fantastic diet aid you may never eat again! Bookmunch

Introduction

It is nearly a decade since the first edition of Not On the Label emerged from a series of investigative journeys I had taken around the global food business.

Those had been shaped partly by my personal experience. I had worked for a couple of years in Pakistan on the Afghan border and, having been isolated from Western culture for a long stretch, on my return I found myself looking at it through different eyes, as though for the first time. Having lived among refugees in an area where food could never be taken for granted, the contrast back in London was dramatic. Here people struggled with overeating and the diseases of excess rather than the diseases of malnutrition and hunger.

The march of the supermarket across our food culture, well under way when I left, was almost complete by the time I came back. There was a cornucopia of plenty at every journeys end but the destination mostly seemed to be a retail car park. Seasons, so prominent in the bazaars of Central Asia, had been abolished in favour of a permanent transcontinental summer time on the high street. It looked awesome. It had removed the daily grind of shopping that had consumed the time and energy of women (mostly) of the previous generation. I wondered if a genius in a white lab coat had invented it while I was away.

But there was something missing from this way of producing, selling and consuming food that seemed to reflect a deeper societal malaise. Human interaction had been reduced to a hurried minimum. There was no scent and little taste to much of the fresh food on offer. The infinite variety on the aisles so often turned out to be just fifty variations on the same over-processed combinations of denatured commodity ingredients high in salt, sugar and fat, despite being packaged and marketed as different brands. There was so much waste.

For all the sophistication of food production in Europe, there was a sense of loss. Independent shops and markets were disappearing. Unpackaged, unprocessed food that had not passed through the mill of big chains was hard to find, and even harder to find at an affordable price. Farmers struggled to make a living. The system was a miracle of logistics and a response to our ever busy and changing lifestyles, but in gobbling sandwiches furtively at our desks, wolfing fast food on the run or throwing together a meal of pre-cut chicken and ready chopped vegetables to consume in front of screens, much of the cultural significance of shared meals had been sacrificed. And in those places where meals were given time and significance, it was at the other extreme. Foodie feasts and high-end restaurants were so hung up on provenance you practically needed a bank loan to indulge in their dishes. I remembered the simple meals from communal bowls set on a Baluch carpet in a refugees mud house, where the business of eating was serious. It wasnt just about refuelling as efficiently as possible, it was the focus of human exchange. The simplest things could be the most delicious. Sitting together over food was where adults shared news and views, where children learned to communicate, to defer to the needs of others and were socialized.

Oddest of all, given this abundance and all the technology that created it, everyone back home seemed worried about their food. Food poisoning had been a regular part of life abroad in an under-developed and war-torn region, but why did so much anxiety surround food even in the affluent West? All the hi-tech hygiene and computerized traceability systems of which the industry boasted seemed unable to keep a series of crises in their complex global chains at bay. Each of these revealed the dysfunction at the heart of our food system.