The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

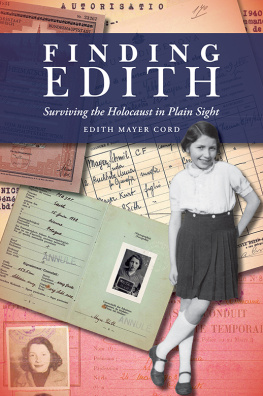

For Edith and for my dad, William M. Martin Jr.

Contents

I finally moved the cookies.

They were Walkers Pure Butter Shortbread cookies, the only brand of cookies Edith liked. They came from Scotland, and when you would eat them it was like you just ate a tab of butter. I remember she sent me to the store for cookies once, and they didnt have her brand, so I brought not one, not two, but three others home. She took a bite of each one, and pushed them back at me. All yours, she snapped, staring up at me with those piercing blue eyes. Not mine.

It was always a battle of wills with Edith.

I eventually hunted down the Walkers at the old Ballard market. When I brought them home, she took one bite and said, Well, that was worth waiting for, dont you think? Like she was a schoolteacher whod just taught her problem student a simple lesson. There I was, a fifty-year-old man, a person with a position of responsibility, and she still made me feel like a kid, every single time.

After she died, and for the longest time after that, I couldnt touch anything in her house. Like that box of cookies. It just sat there on the shelf next to the stove in that cramped kitchen, staring down at me, as if it was daring me to throw it out. Like it knew I wouldnt. I was going to take the cookies over to the trailer at the construction site and let the boys have them. I brought the box to the door twice, at least, and set it down, and thought, well, Ill get it when I go out. But when I was leaving, I just couldnt take the cookies. I couldnt leave them sitting by the door, either, because Edith would hate it if anything was out of place. So Id pick them up and put them back on the shelf, right where they belonged, lengthwise, with the name Walkers showing on a bed of Scottish plaid.

I guess I just wasnt ready.

Im sitting in her house right now for what will probably be the last time, and looking at all this stuff, and wondering why it has such an effect on me. For the last couple of months, Ive come over here, trying to pack up her things. Theres just so much. The music alone is going to take half a day. Theres the albums, hundreds of them: Mantovani, for example. Maybe thirty of those. Who the heck has thirty Mantovani albums? And tons of Guy Lombardo. Then all these cassettes on the wall, in a cheap little wooden cassette case thats sagging in the middlecassettes of Caruso and Beethoven and Benny Goodman. And CDs. Hundreds and hundreds of CDs. I guess she moved along with the times, up to a pointthe albums, then the cassettes, then the CDs. The progression stops there, but still, its kind of funny to see so many CDs in a house where everything else feels like its straight out of the fifties. Anyway, Id come here to pack stuff up, then walk around in circles for fifteen minutes, and leave without touching anything.

Even after all this time, whenever I walk in that front door, I expect to see her lying on the couch. I havent sat on that couch even onceI cant bring myself to sit on it, the couch she lay on every day and slept on every night. I think I havent moved anything because she was just so particular that everything went back exactly where it was. There are hundreds of little ceramic figurines all over this placelots of cows, and some little dogs and cats. She loved animals: heres a ceramic cat at a piano that says Meow-sic and a begging dog and a bunch of little ceramic pigs. And back in the kitchen, she had the figurines from the Red Rose tea boxes. I dont think she even liked the tea all that much, but she loved those little figurines. I read somewhere that Red Rose has given away 300 million of those little toy statues. Sometimes it feels like Edith had half of them.

And if you moved any of her figurines, anywhere in the house, shed notice and get heartburn. One time my wife and daughter came down here to clean up the house a little, and the next day Edith was so irritated. Wheres this? and Whats that doing over there? she said to me. I asked her, what does it matter, but that just made her more irritated because she wanted things where they belonged. Maybe its because thats where her mother kept things. Edith had a really strong connection with her mother, and a lot of things changed when her mother died. Or I guess its more accurate to say, a lot of things had to stay the same.

I think a lot of people face this when their parent dies. Edith wasnt my mother, of course, and in a lot of ways I felt more like a parent to her, taking care of her like she was a child, not to put too fine a point on it. I still faced those same issues, though. The difficulty of accepting that shes really gone. You question yourself: Did I do everything I was supposed to do? I think that until you answer that question, you cant accept whats happened. Maybe thats why I kept everything just where it was, like in a state of suspended animation, while I thought about it.

It was such a strange turn of events that brought me into this little house. There I was, just going to work every day, a project superintendent in charge of building a shopping mall on a lot that was empty except for this one little ramshackle house we had to build around. It wasnt my fault that there was this struggle between the project and this ladys house. Its just the job. The developers were trying to get her to move. She was digging in her heels, insisting that she was going to stay. And there was me, caught in the middle. Everyone thought I was trying to trick her into moving. But the truth was just the opposite. I was doing everything I could to allow her to stay.

So what, you might ask, was I doing over there? What was in it for me?

Good question.

* * *

I guess, if you try to dissect the friendship that formed between usand a lot of people seem to want to do thatyou could start with the books.

Over on one wall, next to the couch, there was a whole collection of classic books, like Wuthering Heights and Canterbury Tales and Das Kapital and the poems of Longfellow. They were all dusty, like no one had read them for a long time, but every once in a while shed quote from them, so I know she read them all, some more than once.

I think thats one of the things that drew me in. I was fascinated with how much she knew. I guess thats because I never met anyone who had read as much, who knew as much, as Edith did. It was like meeting someone from another planet. A different kind of intelligence. It just draws you in.

And then, of course, there were the stories. Ediths stories.

For a guy like me, growing up like I did, you didnt exactly run into people every day who told you they were Benny Goodmans cousin. Or who taught Mickey Rooney some dance steps. Or escaped a Nazi concentration camp. Or said they did, anyway.

Heres exactly what I thought of that, at first:

Wack job.

Not very nice, I know. But thats where I was at, pure and simple.

But as I started to go over there more often, and heard more and more of the storiesjust little bits and pieces of them, just enough to make you wonderI found myself wanting to hear more. Looking at Edith was a little like looking at those books: a million stories hidden in there. Maybe half of her stories werent true. But it was real interesting, just to know they were there.