Table of Contents

ALSO BY DAVID LIDA

Travel Advisory

Las llaves de la ciudad

(a collection of journalism, written in Spanish)

For Francisco Goldman,

and In memory Of Aura Estrada

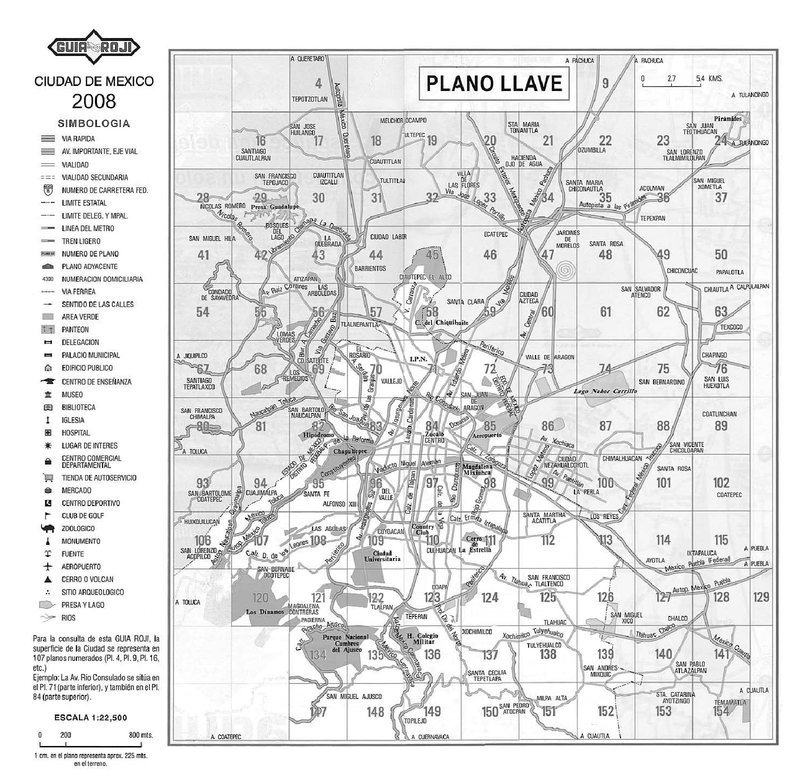

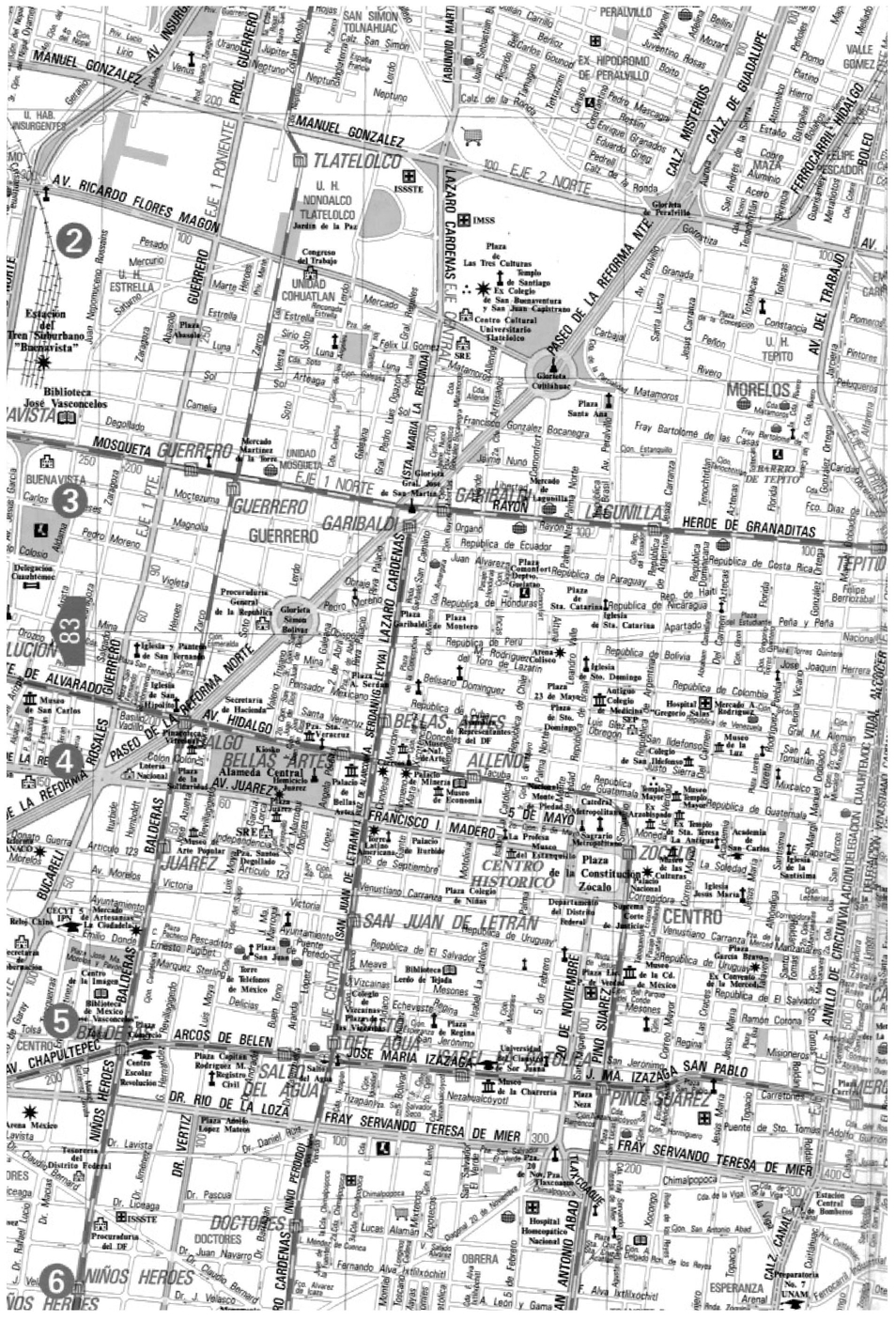

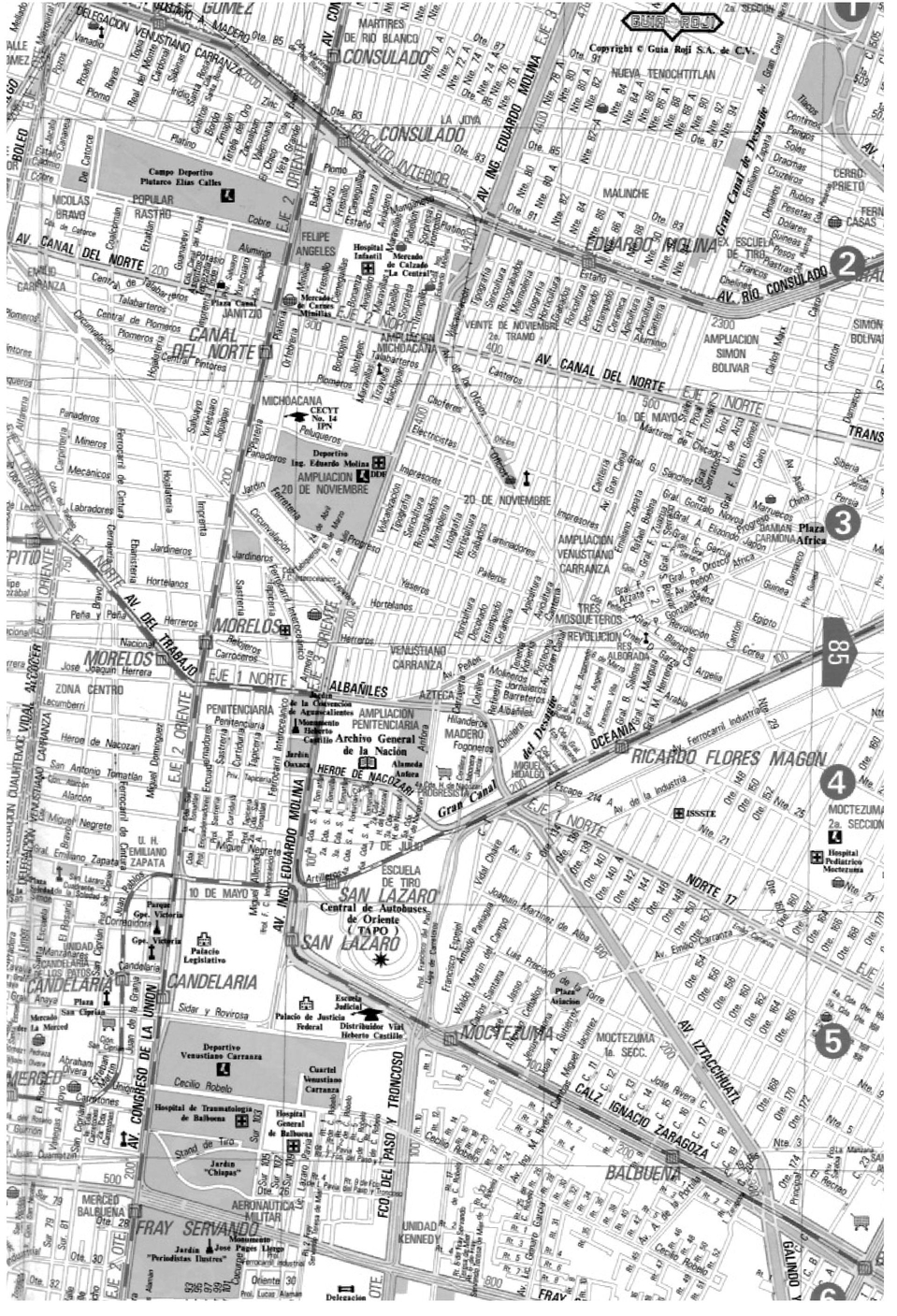

Citizens of Mexico City rarely use maps to get around their constantly expanding metropolis. But if they do, they use the Gua Roji, a book that divides the urban sprawl into 154 separate sections. The image above is Gua Rojis back page, an attempt to give an overview of the city. Each numbered box indicates a more detailed map with actual streets and monuments. On the following pages is Map 84, which covers downtown and the centro histrico. Apart from its multiple maps, Gua Roji, which is updated each year, also includes a 250-page index of street names, colonias (neighborhoods), and landmarks, and its own magnifying glass so you can read the tiny print.

Introduction: The Hypermetropolis

From my first visit as a tourist, Mexico enchanted me. I kept returning, but for four years didnt dare set foot in Mexico City. I was afraid of the capital, influenced by the propaganda dismissing it as a teeming, overpopulated, polluted bedlam, full of horrific testimonies of insuperable poverty. I imagined the armless beggars of Calcutta brandishing their stumps in tourists faces, hoping the display would result in a handout.

Then, during one holiday in 1987, I had a layover in Mexico City. In the hour-long taxi ride from the airport to the hotel, I fell in love. I was astonished by the streets of the centro histrico, lined with massive stone buildings constructed by the Spanish conquerors in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. I was captivated by the contrast between the grandiosity of those structures and the humility of the office workers wending their way through the sidewalksthe smiling shoeshine man at his electric-orange post, the doughy matron in the blue skirt and white apron beseeching me to buy tacos sudados sweaty tacos, so called because they are steamed in a basket.

That afternoon I sipped coffee on a hotel balcony overlooking the zcalo, the citys enormous central square. A crowd began to gather in support of a teachers strike. By twilight they would be one hundred thousand strong, yet an hour later everyone was gone, the plaza empty, as if it had been a hallucination.

At night I wandered along those streets dense with history, lit so dimly they appeared to be in black-and-white. In a crowded cafeteria, I ate tamales wrapped in banana leaves and stuffed with spicy pork. I drank tequila in a dark bar, where a round man with slick hair and a pencil mustache sang romantic songs, backed by three guitar players dexterously crowding notes into each phrase.

I stumbled upon Plaza Garibaldi, the rowdy nocturnal soul of the city. Squadrons of musicians, mostly mariachis in skintight, tin-studded black suits, trawled for customers willing to pay a few pesos for a melody. When they found temporary patrons, throngs gathered, and the most boisterous revelers sang along. It was a crowded Friday night, and the result was the most singular cacophony Id ever heard.

In Garibaldis most humble cantina, La Hermosa Hortensia which dispenses pulque, a fermented cactus beverage created by the Aztecsa staggeringly drunken man offered me his wife. She demonstrated her eagerness to consummate the proposition with a squeeze of my thigh and a smile, the seductiveness of which was undercut by the absence of several crucial teeth. I refused with as much courtesy as possible, after which the man removed from his neck, and gave me, a string that held an emblem of Mexicos patron saint, the Virgin of Guadalupe.

Before I went to bed, half-drunk in the wee hours, I watched a lonely group of soldiers in ill-fitting uniforms on drill in the otherwise empty zcalo. Unfortunately, I had to leave the next day. I had been utterly seduced by the constant sensations of contrast, surprise, even tumult. Within three years I would be living there.

That MEXICO City was such a beguiling place came as a complete surprise. The 1980s were surely the worst moment in its history. Three million autos, the thin air of its 7,300-foot altitude, and the thirteen thousand factories that ringed the valley in which it is situated created an ecological nightmare with toxic levels of pollution.

The pumping of a billion gallons of water per day from as far away as fifty miles caused the city to sink 3.5 inches a year, and the lack of adequate plumbing and drainage made it a nightmare for many of its residents.

Said to be the biggest city in the world, by the early 1980s Mexico City had a population of seventeen million, and the government predicted that there would be thirty-six million by the year 2000. Most of the new inhabitants were squatters, streaming in from the impoverished countryside at a rate of a couple of thousand per day, creating slapdash shantytowns on the ever-expanding outskirts.

In the immediate aftermath of a devastating earthquake in 1985 the government seemed to disappear into thin air, and it was up to the citizens to rescue one another from under the rubble. Not only was there a lack of viable leadership, but politicians and police chiefs were noted more for how much they stole from the public trough than for any constructive projects they carried out.

If Mexico City today is still a challenging and sometimes exhausting place to live, with permanent service problems (principally in drainage, water pumping, and distribution) and a continued resistance to urban planning, it is worth pointing out that the worst predictions from the 1980s did not come to pass.

While pollution levels may still be unacceptably high, the situation is no longer a noxious horror. Since 1991, all new cars here have come with catalytic converters, and although four million or so make traffic a nightmare, they are not causing as much lethal damage as they did twenty years ago. Most of the factories in the valley have closed down, making way for a greater service economy and cleaner air. Plumbing has reached virtually 100 percent of the city, even in the most impoverished outskirts.

Mexicos is the second most dynamic economy in Latin America, after Brazils, but its wealth is scandalously distributed. While Mexico Citys gross domestic product is over seventeen thousand dollars U.S. per capita, half of the capitals residents live at or near the poverty level, and about 15 percent beneath it. At the same time, virtually everyone has a roof over his or her head, electricity, running water, and a TV set. More than half have cell phones. If someone starves to death in the capital, it is an anomaly. (This is in contrast to other parts of Mexico, mainly rural, that the United Nations has compared to Africa for their destitution.)