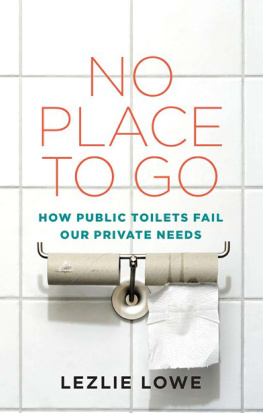

copyright Lezlie Lowe, 2018

first edition

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. Coach House Books also acknowledges the support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit.

LIBRARY AND ARCHIVES CANADA CATALOGUING IN PUBLICATION

Lowe, Lezlie, 1972-, author

No place to go : how public toilets fail our private needs / Lezlie Lowe.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-55245-370-4 (softcover).--ISBN 978-1-77056-561-6 (EPUB).-- ISBN 978-1-77056-562-3 (PDF)

1. Public toilets--Social aspects. 2. Restrooms--Social aspects. I. Title.

GT476.L69 2018 | 392.36 | C2018-903922-1

C2018-903923-X |

No Place To Go is available as an ebook: ISBN 978 1 77056 561 6 (EPUB) ISBN 978 1 77056 562 3 (PDF)

Purchase of the print version of this book entitles you to a free digital copy. To claim your ebook of this title, please email with proof of purchase. (Coach House Books reserves the right to terminate the free digital download offer at any time.)

For Lily and Georgia, whose early

urban adventures started this whole thing

1

GAME OF THRONES

S pring 2005. I abandon my kids and trundle down the grimy concrete stairs to the public bathrooms in the bunker-like Pavilion on the Halifax Common. Practically every day summer, fall, spring, and winter, doesnt matter I yank on the heavy door, more surprised when it budges than when it doesnt. Getting in is only something of an advantage. These public bathrooms are smelly and soap-free. Theres no changing table, often no paper towels, and the hand dryers have been smashed off the walls. I turn around and climb the stairs to retrieve my girls. To use these city-run facilities, I leave my double stroller and the rest of my belongings outside, crossing my fingers that nothing gets stolen while I help a toddler down the stairs, balancing an infant and lugging a diaper bag.

I brave it. My bladders weak, always has been. Its not a medical condition. Its just that, when I have to go, I really have to go. Whats more, my feeble ability to hold it far exceeds my toilet-training three-year-olds, so daily down the stairs I tromp to give that handle a yank. Most days, its no go, which means a quick turnaround to head home to pee or change someones pants. Ill learn later that the softball league that uses the diamonds on weekends has copies of the keys; they turn the deadbolts when they leave on Sunday evenings, lest up-to-no-good mothers like me get in and mess up the place.

Im on the Common because its close to my home: a convenient place to go to get the heck out of the house. Being free of four walls with young kids is a prophylactic against maternal madness, and the Halifax Common is a central park on downtowns edge with plenty of grass and trees, and paths for strolling. The Common was set aside in 1749 as a community livestock pasture (the irony here is inescapable this place was, at one time, a giant bathroom). Having banished sheep and cows, the modern Commons twelve hectares hold tennis courts, ball diamonds, a skate park, a swimming pool, and a splash pad. The place is built for leisure. Unless, that is, youre the kind of person who uses the bathroom.

Every time Im out with my infant and toddler, I need to change a diaper or respond to the urinary urgency of my toileter-to-be. Often both. Every time. Parents reading this know it to be true. So its inconceivable though here I am living it that no municipal workers seem to check that the Common bathrooms are open, let alone clean and stocked. This is simply what passes for a public toilet in Halifax, Nova Scotia, in 2005. And, look, thats no slag on my home city. Halifax is a provincial capital and regional centre with six universities, active arts and sports scenes, and access to the unbounded wild within a thirty-minute drive of downtown. In short: we take quality of life seriously. This same kind of sad-excuse-for-a-public-toilet is what passes in cities and parks all over North America even today.

And this, precisely, is the problem.

Its the reason I carry little girls underwear in my purse. Its the reason Ive developed toilet radar; the reason the first thing I look for in a new environment is the closest place to pee. Its the reason I started to ask questions about public toilets. Like, why arent there more of them, in a developed country with enough money to fund polar and space exploration and to give generous tax breaks to multinational corporations? And how is it that, with kids, I started having so much trouble navigating a city that I used to steer through relatively problem-free? People tell you your life changes once you become a parent. And its true: I sure started seeing public bathrooms differently.

Or, you might say I started seeing them at all. And once I began to think about toilets, I couldnt stop. The more I learned, the more it struck me that the history of public toilets in cities is the history of cities themselves. Toilets have been a central, recurring theme in my journalism practice ever since I wrote my very first piece as a staff writer for Halifaxs alternative weekly paper, the Coast (thats when I found out the softball leagues were the ones locking me out). Public bathrooms are invariably one of the highlights (or lowlights) of my travels. My holiday pics are flooded with public-bathroom shots; I reach excitedly for my Twitter feed when I find a great bathroom sign, like the ones at Edinburghs Meadows park, which include distances along with way-finding. Public bathrooms, so seemingly mundane, keep me up at night. They spell out how unwillingly we share public space, how we would rather pretend we never defecate or urinate (or, for that matter, menstruate). Public bathrooms are private spaces that reveal public truths. I cant help myself. I have to peek inside.

My bathroom fiascos on the Halifax Common arent just my stories; they are the province of parents all over. For most North American kids, the leap out of diapers happens around age three. Toilet training is a time of frayed nerves, when leaving the house goes high-stakes. Kids non-parents may be unaware here give little warning of impending sanitary disaster. It can be zero to puddle in under sixty. And in the miraculous case that a new underpantser is aware enough to give the gotta-go in time, a most pressing question indeed presents itself: where?

I call Andreae Callanan, a friend of a friend in St. Johns, Newfoundland. I want the perspective of a parent in a different city, and one with higher stakes. Callanan has four kids. She knows this game of thrones. I cant even think of how many times my children have had to pee in an alleyway or behind a bush, or a mailbox, she says. You do these things because you have to. This isnt dinner-party conversation. No parent wants to explain that his kid pooped on the playground slide, or describe how he cleaned it up with a McChicken container fished out of the trash. Callanan tells me she once changed a soiled diaper in an outhouse-sized caf bathroom in Montreal, aiming a soggy child into a clean diaper balanced on her lap as the then-new mom sat on a toilet. The nanny of one of my friends is horrified at the lack of public bathrooms in parks in her adopted city of Ottawa. Shes taught her three-year-old charge to pee on the back of the electrical box at one of the parks. I wasnt sure if that was an attempt at privacy, my friend confides, or a passive fuck you to the Parks and Rec department.