C ONTENTS

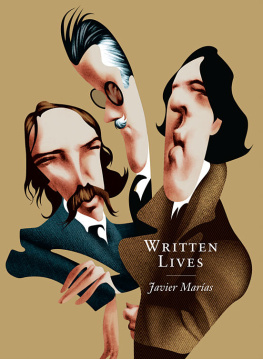

W r i t t e n

L i v e s

To my real father Julin

and to my fictitious sister Julia,

and to the one who waits

P R O L O G U E

THE IDEA FOR THIS book arose from another in which I was also involved: an anthology of very strange stories entitled Cuentos nicos (Unique Talespublished in 1989 by Ediciones Siruela, Madrid), in which each story was prefaced by a brief biographical note about its extremely obscure author. The majority were so obscure that any information I had about them was sometimes both minimal and difficult to unearth and, therefore, so fragmentary and often so bizarre that it looked as if I had simply invented it all, a conclusion reached by several readers, who, logically enough, also doubted the authenticity of the stories. The fact is that, when read together, these briefest of brief biographies constituted another story, doubtless as unique and spectral as the stories themselves.

I believe, and believed at the time, that this was due not only to the strange and disparate nature of the information available about these ill-fated and forgotten authors, but also to the manner in which the biographies were written, and it occurred to me that I could adopt the same approach with more familiar and more famous writers, about whom, converselyas befits the age of exhaustive and frequently futile erudition in which we have been living for almost a century nowthe curious reader can find out absolutely everything, down to the last detail. The idea, then, was to treat these well-known literary figures as if they were fictional characters, which may well be how all writers, whether famous or obscure, would secretly like to be treated.

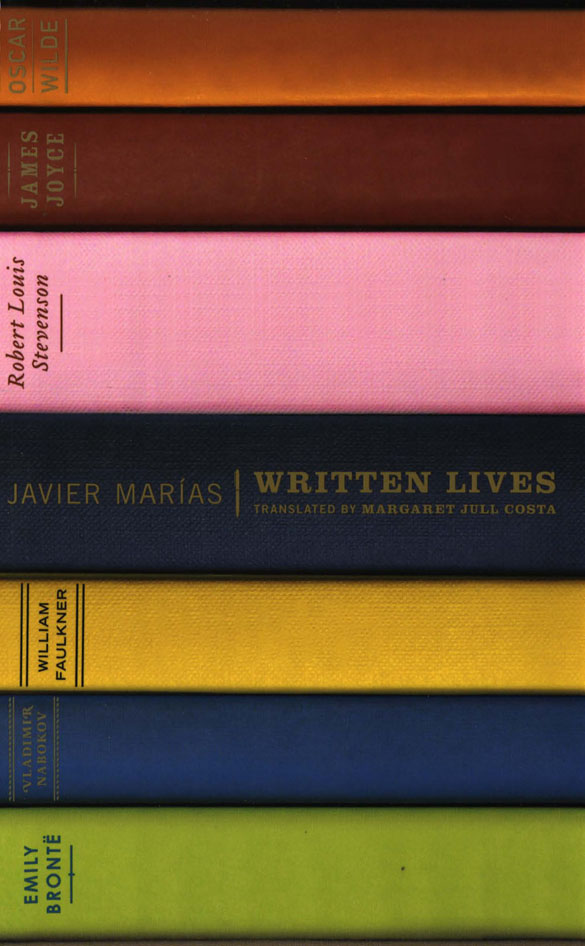

The choice of the twenty who appear here was entirely arbitrary (three American, three Irish, two Scottish, two Russian, two French, one Polish, one Danish, one Italian, one German, one Czech, one Japanese, an Englishman from India, and an Englishman from England, if we are going by place of birth). My one condition was that they should all be dead, and I decided, too, to exclude any Spanish writers: on the one hand, I did not want to encroach, however tangentially, on territory that is food and drink to so many of my expert compatriots; on the other hand, some critics and certain fellow indigenous writers have denied my Spanishness on so many and various occasions now (both as regards language and literature and, very nearly, citizenship) that I have, I realise, ended up feeling rather inhibited about discussing writers from my own countryeven though these include some of my favourites (March, Bernal Daz, Cervantes, Quevedo, Torres Villarroel, Larra, Valle-Incln, Aleixandre, as well as other living authors)and among whom I continue, despite all, to count myself. But its as if those critics had convinced me that I had no right to do so, and one acts according to ones convictions.

This book, then, recounts writers lives or, more precisely, snippets of their lives: I rarely make any judgement about the work, and the sympathy or antipathy with which the characters are treated does not necessarily correspond to any admiration or scorn I might actually feel for their writing. Far from being a hagiography, and far, too, from the solemnity with which artists are frequently treated, these Written Lives are told, I think, with a mixture of affection and humour. The latter is doubtless present in every case; the former, I must admit, is lacking in the case of Joyce, Mann, and Mishima.

There is little point in trying to draw conclusions or lay down rules about the lives of writers on the basis of these portraits: what I reveal in them is very partial, and it is precisely in what is included and what omitted that the possible accuracy or inaccuracy of these pieces partly lies. And although almost nothing in them is invented (that is, fictitious in origin), some episodes and anecdotes have been embellished. Anyway, the one thing that leaps out when you read about these authors is that they were all fairly disastrous individuals; and although they were probably no more so than anyone else whose life we know about, their example is hardly likely to lure one along the path of letters. Luckily, at leastand this should be emphasisedit is clear that none of them took themselves very seriously, apart perhaps from the above-mentioned exceptions, the ones who failed to win my affection. However, I wonder if the lack of seriousness in these texts emanates from the characters themselves or from the views of their accidental, extempore and partial biographer.

For the benefit of the suspicious reader who wants to check some fact or to detect any embellishments, I provide, at the end, a bibliography, although the said reader will find most of the titles listed very difficult to locate.

This series of Written Lives was first published in the magazine Claves de razn prctica (nos. 2-21), while the section entitled Perfect artists, which closes the volume by way of a negative (it is solely about faces and gestures), appeared in the magazine El Paseante (no. 17). I am grateful to the editors of the former, Javier Pradera and Fernando Savater, for the gentle and encouraging tyranny they wielded over me and to which the writing of these lives is, in large measure, due.

J.M.

February 1992

P.S. Seven years and seven months later

This new edition of Written Lives contains only a few changes relative to the previous edition, but there is no harm in pointing these out.

A couple of lives have been slightly retouched and expanded, the rest remain unchanged. Most of the photographs that precede each life are different from those in the 1992 edition (the latter were chosen by Jacobo Fitzjames Stuart, the publisher, and those in this edition by me).

There is a new section, new, at least, to this book (I did at one time include it in Literatura y fantasma [Literature and Phantasm], 1993), entitled Fugitive Women, written after the 1992 publication of Written Lives, but very much in the same spirit, which is why this volume of brief biographies is the most suitable place for it. These pieces first saw the light in the magazine Woman (issues published May-October 1993).

As regards what I wrote in the Prologue seven years and seven months ago, the conviction I referred to then has become more widespread and more firmly established. And to my list of favourite Spanish authors I should now addsince he is no longer livingJuan Benet.

With the passage of time, I have come to realise that, although I have enjoyed writing all my books, this was the one with which I had the most fun. Perhaps because these lives were not just written but read.

J.M.

September 1999

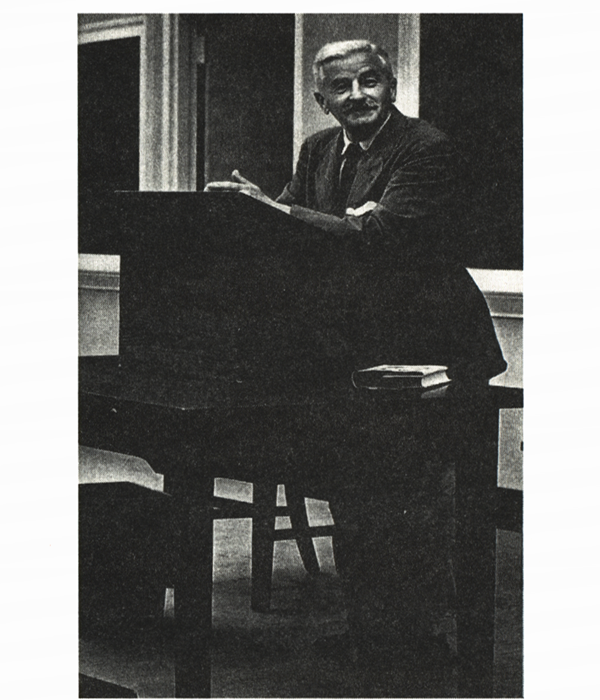

W ILLIAM F AULKNER ON H ORSEBACK

ACCORDING TO SOMEWHAT kitsch literary legend, William Faulkner wrote his novel As I Lay Dying in the space of six weeks and in the most precarious of situations, namely, while he was working on the night shift down a mine, with the pages resting on an upturned wheelbarrow and lit only by the dim rays of the lamp affixed to his own dust-caked helmet. This said kitsch legend is a clear attempt to enlist Faulkner in the ranks of other poor, self-sacrificing, slightly proletarian writers. The bit about the six weeks is the only true part: for six weeks one summer he made the most of the long, long intervals between feeding spadefuls of coal into the boiler he had been put in charge of in an electrical power plant. According to Faulkner, no one bothered him there, the continual hum from the enormous old dynamo was soothing, and the place itself was otherwise warm and silent.