Bernard Farai Matambo casts images that quiver with terror and desire. These images root within us as if we were the very landscape the poet renders spectral with the residue of human passions: cities of ruined arches and potshards underfoot, the human cost of conflict, populations bowed in reverence and fear. Matambo is an archer of lyric poetry. His words are drawn out and taut, anxious as catapults.

Gregory Pardlo, author of the Pulitzer Prizewinning Digest

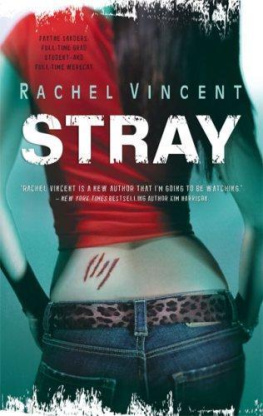

Stray is a work of great sensual intelligence and evocative urgency, consistently intimate and political. With painstaking concentration and dazzling lyricism, Matambo dismembers the cult of pitiless masculine strength and paints a portrait of a half man, half anger in the empire of the zoo. Then he puts this man with an ape inside him through the meat mincer of African and American histories. Matambos short prose poems are gulped down like bitter pills of remembrance and forgetting.

Valzhyna Mort, author of Collected Body

Lush, yet urgent, determined to design a language that can feed the hunger for truth.... Follow Matambos poems as they stray from Zimbabwe to the U.S. and back, through landscapes haunted and illuminated by unforgettable images: Once I caught a bough leaping into the air, a thicket of birds lifting off of it, dissolving among the stars.

Evie Shockley, author of semiautomatic

Stray

African Poetry Book Series

Series editor: Kwame Dawes

Editorial Board

Chris Abani, Northwestern University

Gabeba Baderoon, Pennsylvania State University

Kwame Dawes, University of NebraskaLincoln

Phillippa Yaa de Villiers, University of the Witwatersrand

Bernardine Evaristo, Brunel University London

Aracelis Girmay, Hampshire College

John Keene, Rutgers University

Matthew Shenoda, Columbia College Chicago

Advisory Board

Laura Sillerman

Glenna Luschei

Sulaiman Adebowale

Elizabeth Alexander

Stray

Bernard Farai Matambo

Foreword by Kwame Dawes

University of Nebraska Press | Lincoln and London

2018 by the Board of Regents of the University of Nebraska

Acknowledgments for the use of copyrighted material appear in , which constitute an extension of the copyright page.

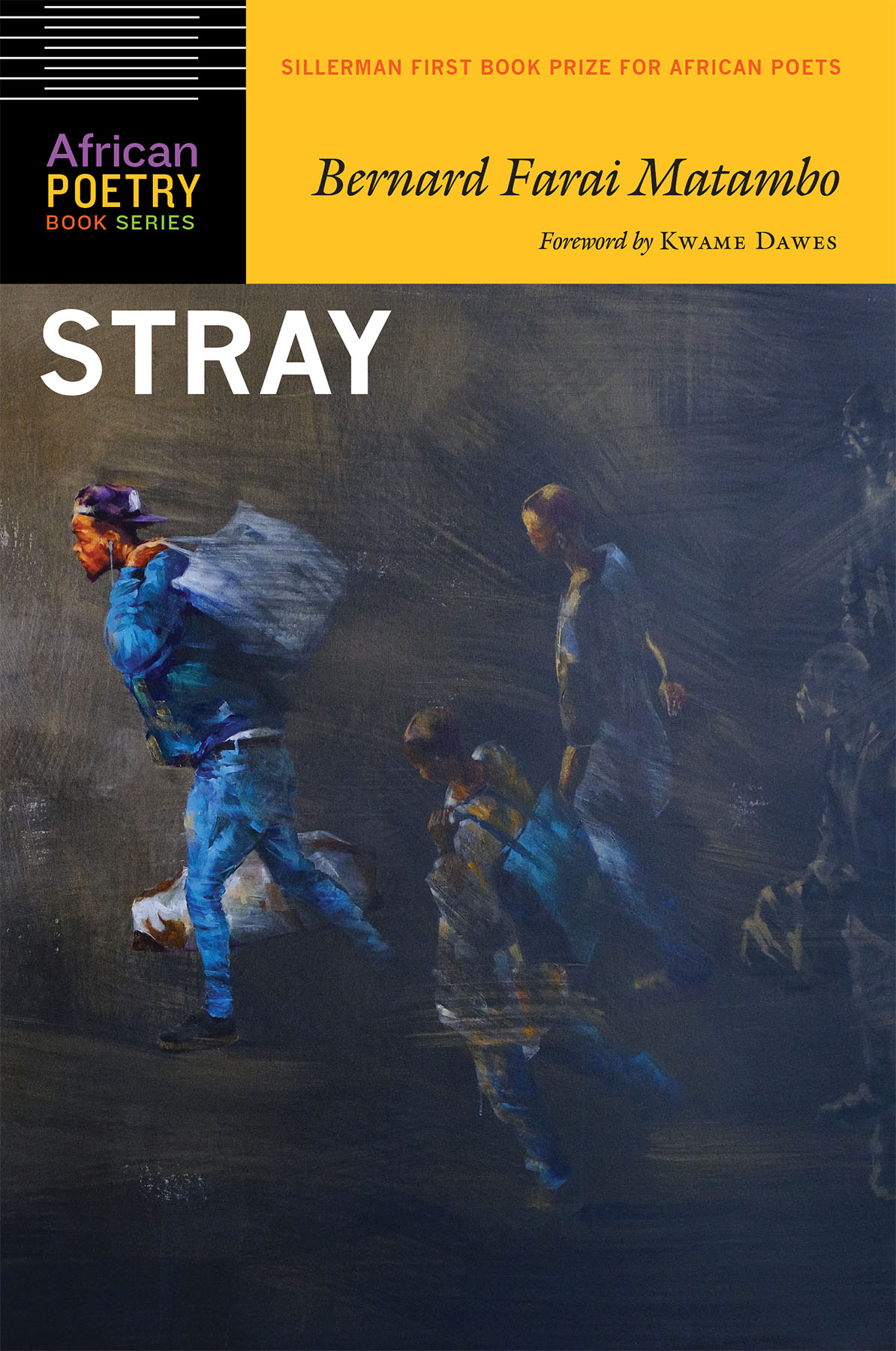

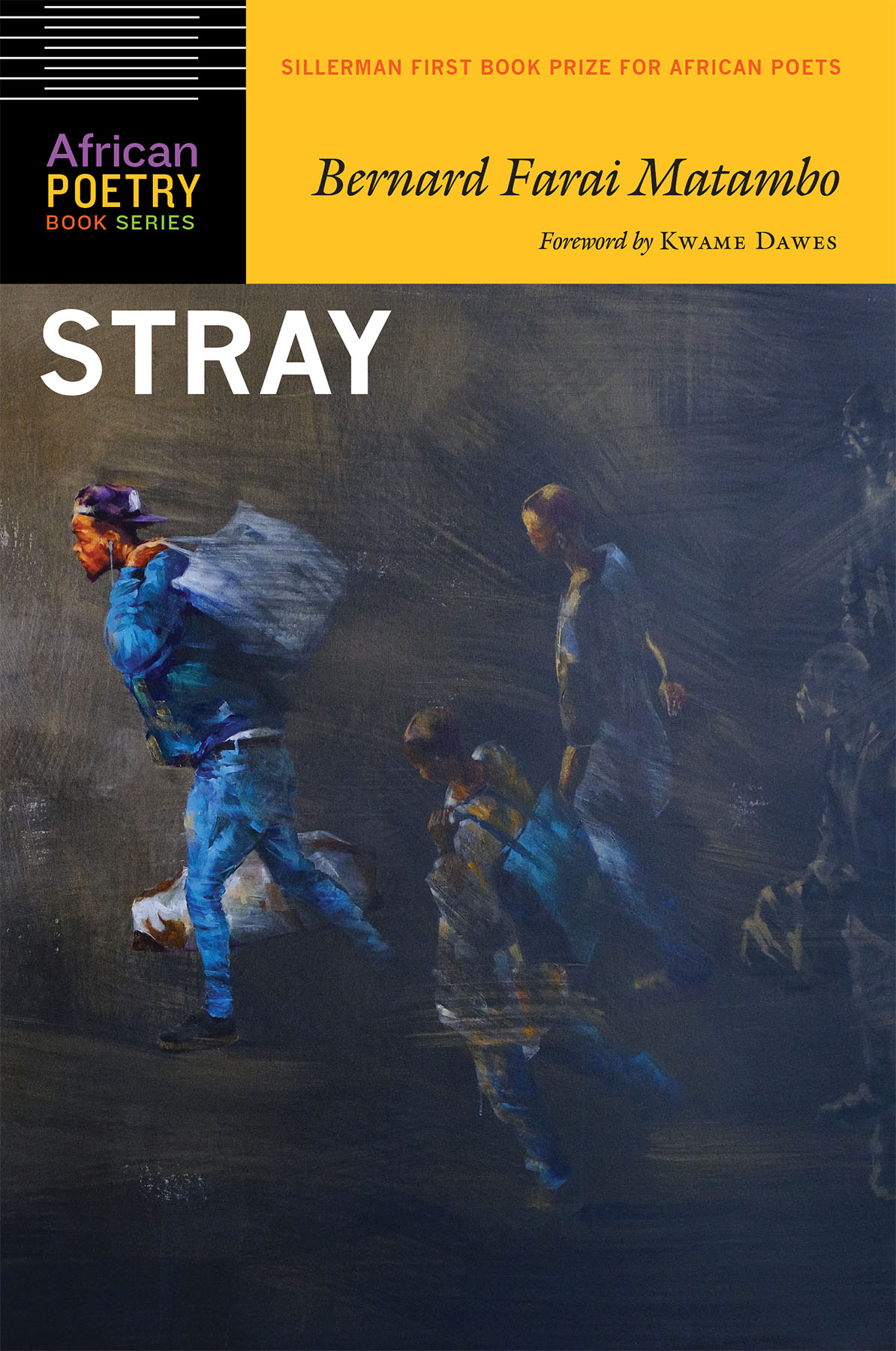

Cover designed by University of Nebraska Press; cover image Charles Bhebe.

Author photo Gwendolene Mugodi.

All rights reserved

The African Poetry Book Series has been made possible through the generosity of philanthropists Laura and Robert F. X. Sillerman, whose contributions have facilitated the establishment and operation of the African Poetry Book Fund.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Matambo, Bernard Farai, author. | Dawes, Kwame Senu Neville, 1962 writer of foreword.

Title: Stray / Bernard Farai Matambo; foreword by Kwame Dawes.

Description: Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, [2018] | Series: African poetry book series

Identifiers: LCCN 2017043648 ISBN 9781496205582 (hardcover: acid-free paper) ISBN 9781496207791 (epub) ISBN 9781496207807 (mobi) ISBN 9781496207814 (pdf)

Classification: LCC PS 3613. A 822 A 6 2018 | DDC 811/.6dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017043648

The publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party websites or their content.

Contents

Kwame Dawes

Bernard Matambos Stray joins an illustrious group of debut collections in this series. Matambos penchant for the prose-shaped line, and his persistent sense that contradictory impulses in poetry are necessary for a poet in search of emotional and intellectual truth, shine throughout this moving collection of poems. Yet what remains as the hallmark of these poems is their reach for images that reflect invention and precision: The mountains were full of song, their trembling not our enemy (All the Merry Hills).

Matambo takes us through several key familial (father, brother, and mother) relationships that have symbolic value, as each allows him to explore broader issues of identity, place, and ideology in intellectually complex ways. In poems that explore the legacy of a masculine indiscretion and cruelty, there is a clear sense that the son is seen as an inheritor of sins from the father. Rather than blame, the speaker appears to be caught in an inevitability, a twisted notion of a birthright. And in this, there is in the beauty of the language, the invention of description, a quality of empathy caught in the memory of a father who whimpers after orgasm with his long-suffering wife, a man at once flawed and, thus, human:

It was a sport I knew little of then

except for the beads in the corners of his eyes

when he returned delicate with his thunders.

(In the Name of the Tongue)

The father, though, will fail, and the mother will leave. The father, caught in both regret and a strange kind of unhinged hope, waits for her return, expecting it, even as he holds onto the one thing he has left: the totems of his tribe. Again and again, Matambo offsets a penchant for acrimony and blame by turning these poems of censure into poems of quiet confession: Sometimes I catch him in the taste of my tongue (In the Name of the Father).

In the opening poems, Matambo variously describes the legacy of the speakers father as a stain, an inheritance, a taste, and a residual sense of self; and much of what gives these poems tension is their attempt to outline what is clearly religious hypocrisy with the necessity for respectif not love. These poems move through narrative confessions on behalf of the father into a reluctant sense of complicity: It all begins with the stain of him, the marrow / leaking out into the bone (Holy Ghost).

The stain returns around matters of faith and desire. And in this, Matambo writes as a poet excavating themes that haunt the young writerthe discovery of desire, the disquiet and excitement of troubled faith, and the hunger to find language to express all of this. He is both ironic and sincere in the belief that poetry cannot contain these feelings:

Remind me again, dear love, of that time when the world was as young as we were and I was lit bright with urges, light as the shroud Christ yielded when he gave up his tomb, sick of sleeping alone and dreading the eternity of it, when he sought himself some company. Of this no poetry shall come.

(Catechism)

The father functions as an intellectual trigger for the poet such that even as he contemplates, in the brilliantly realized long poem that explores the story of Ota Benga (Ota Benga Returns to the Congo), it is the father who Matambo connects with Benga before making his own symbolic connection to the complex figure. Ota Benga, of course, is the Congolese man who at the turn of the last century was made a spectacle of in the United States as a zoo dweller:

I remember nothing of what riled the orangutan

inside the cage deep inside my father, the one

he concealed so long and deep in him like a bad habit

until it too raged for its freedom, and my father placed his pistol

on De Boers ear. I too sometimes hear its rolling call in my bones.

From that connection created by a drunk fathers witty reflection, Was Ota Benga the first Afropolitan we arrive at the call in my bones of Matambo, whose task is to find a thread of connection even as he is coming into his ownstraying, as it were from home. But what remains strikingly inventive and impressive about Matambo is the complex thinking that allows him in this poem to offer a very contemporary examination of the persistent relationship between the West and Africa and how it is played out in the intimate place of the psyche. Ota Benga, Saartjie Baartman, Matambos father (whose narrative includes an act of violence that is heightened by the willful treatment of it as something that could be more than symbolic), and Matambo himself are deeply connectedthey are wrestling with the idea of being viewed as subhuman spectacles by white culture and with the implications of return to the motherland once the knowledge of what is out there has corrupted them.