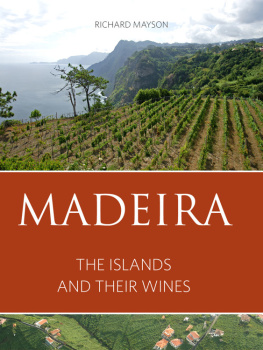

THE CLASSIC WINE LIBRARY

Series editor: Richard Mayson

Cognac: The story of the worlds greatest brandy , Nicholas Faith

Port and the Douro , Richard Mayson

Sherry , Julian Jeffs

Vines and vineyards

Madeira can lay claim to the worlds original varietal wines. The words Sercial, Verdelho, Bual and Malvasia (Malmsey) appeared stencilled on bottles long before Chardonnay or Cabernet Sauvignon entered the lexicon of the modern wine label. Madeira wine enthusiasts consequently have a longstanding interest in the make-up of the islands vineyards, which have been in a state of constant flux ever since the early settlers planted the first vines in the fifteenth century.

The vines

The white Verdelho grape was the principal variety growing on the island before the twin plagues of oidium and phylloxera, with Terrantez and Malvasia planted in much smaller quantities but always the most highly prized. From the 1870s onwards there was a seismic shift with high-yielding, disease-resistant grape varieties largely ousting the classic varieties. A red grape called Tinta Negra Mole (now known officially as Tinta Negra) was the chief beneficiary of the upheaval but, until as recently as the early 1990s, over half the islands wine production came from so-called , the direct producers yield well and are disease resistant. Consequently they were popular with small growers looking to maximise their returns. Grapes from ungrafted Vitis labrusca and Vitis riparia (and the hybrids derived from them) are much less good for fortified wine than the European vinifera vines and were mostly used to make inexpensive madeiras and unfortified rustic table wines for local consumption. However, red hybrid varieties like Isabella, Jacquet, Cunningham (known locally as Canim) Hebremont, Isabella and Jacquet (sometimes spelt Jacquez), all extensively planted post-phylloxera, had some support among the shippers. Peter Cossart (the younger brother of Noel Cossart at Cossart Gordon who was responsible for the wines of Henriques & Henriques for over fifty years) always claimed he liked the direct producers and that they made some good wines. High yielding, sweet and probably naturally acidic, they were indeed capable of producing some reasonably good wines, particularly in years when the vinifera varieties were disease ridden. But there is no getting away from their so-called foxy, rustic character. There is no knowing how much of this wine entered into fortified madeira blends post-phylloxera, often masquerading as one of the so-called noble varieties.

All grapes from direct producer and American hybrid vines contain a substance called anthocyanin diglucoside, known locally as malvina . This is thought to be carcinogenic and it is sometimes claimed that malvina causes mental disorders, although there is no proof of it leading to either condition. It was always technically illegal to produce madeira from the direct producers, but production figures show that from the 1950s through to the end of the 1970s between two-thirds and three-quarters of the islands grape production came from them. Most of these vineyards were on the north side of the island (although figures from the 1980s show that there was still plenty in Cmara de Lobos, Ribeira Brava and Calheta on the south coast and some of the Madeira Wine Companys vintage reports from the 1980s still smack of desperation at the lack of good quality grapes). At the end of the 1980s, Jacquet was fetching 40 escudos a kilo whereas Tinta Negra sold for 180 escudos a kilo. The ban on direct producers was only enforced following Portugals accession to the then EEC in 1986. All wines were subsequently routinely tested for malvina by the Madeira Wine Institute (IVM) but apparently it is difficult to detect malvina in a wine that is more than ten years old. Although large areas of vineyard planted with hybrids and direct producers have since either been replanted or abandoned, according to current estimates there are still more non- vinifera vineyards (i.e. direct producers) on the island than vinifera, . There is still a substantial local market for so-called vinho seco (also referred to as vinho americano or morangeiro), a light acidic red wine which smells alarmingly of synthetic strawberries.

Men who shaped madeira

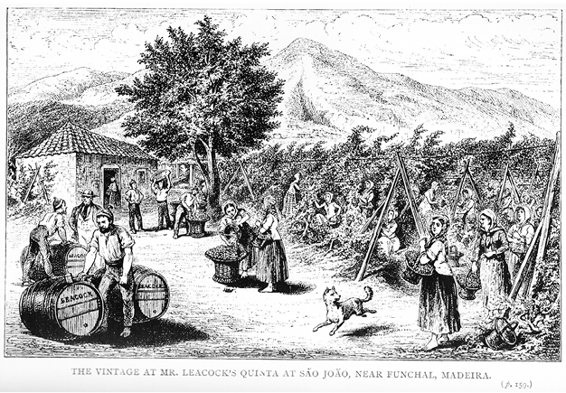

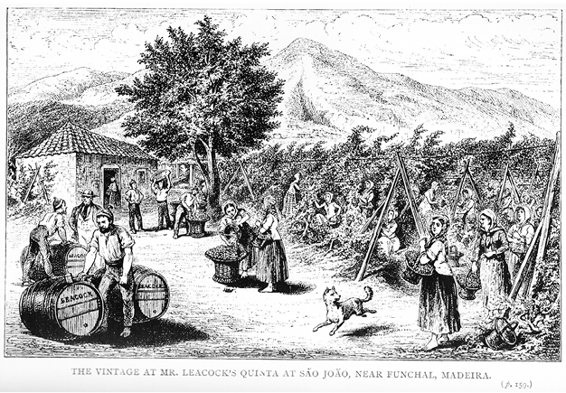

Thomas Slapp Leacock (18171885?)

The grandson of John Leacock who founded the eponymous firm in 1758, Thomas Slapp Leacock was in charge of the business when phylloxera took hold on the island in the 1870s. He was one of the leading zoologists of his day (an authority on snails) and conducted experiments with electricity. But his fame comes from the work he undertook at the Alto do Pico de So Joo vineyard which is documented by Henry Vizetelly. Leacock was the first person on the island to identify phylloxera and in 1873 he was already experimenting with various treatments to combat the plague. He began by treating the roots of his vines with resin and essence of turpentine and later used tar to protect the roots from the phylloxera louse. He also used copper sulphate to combat the aerial form of the disease and, in his own vineyards, he had managed to control the disease by 1883. Thomas Slapp Leacock is credited with saving some of Madeiras traditional grape varieties from extinction, and his research was donated to Cambridge University.

The quality of Madeiras wine grapes has improved immeasurably since the 1990s, with large swathes of vineyard having been either abandoned or replanted. Under two EU-financed schemes dating from 2001 to 2011, 300 growers replanted 99 hectares of vines. Although smaller in area and fewer in number, the majority of vineyards are now better tended than at any time since the mid-nineteenth century. The legal minimum ripeness for grapes destined to produce madeira wine is a mere 9 Baum (roughly equivalent to 9% abv, or alcohol by volume), with an exemption for Sercial, even the best of which often struggles to reach this level of ripeness. In practice, the 9 Baum minimum has only been rigorously enforced by the authorities since 2004. It means that there is now more of an incentive for growers to produce a smaller but better quality crop.

Once categorised as nobre (noble), boa (good) or merely authorised, the official classification of Madeiras vinifera grapes has now been simplified into two categories: recommended and authorised. The traditional grape varieties that predate phylloxera (Sercial, Verdelho, Bual, Malvasia and Terrantez) are the most highly valued and still produce the best and most sought-after wines. The following grape varieties are currently permitted for the production of madeira wine:

Recommended varieties (Castas recomendadas)

White (brancas): Sercial, Verdelho, Malvasia Fina (Boal), Malvasia Cndida, Malvasia de S o Jorge, Moscatel Grado, Folgoso (Terrantez), Listro

Red (tintas): Tinta Negra, Bastardo, Tinta, Malvasia Candida Roxa, Verdelho Tinto

Authorised varieties (Castas autorizadas)

White (brancas): Caracol, Rio Grande, Valveirinho

Red (tintas) : Complexa, Deliciosa and Triunfo.

Recommended varieties

The following varieties are currently (February 2015) recommended by IVBAM. In the profiles that follow I am grateful for first-hand information from Andrew Blandy at Quinta de Santa Luzia, Funchal, and his consultant viticulturalist Eng. Gonalo Caldeira of the Madeira Wine Company. The varieties below are listed in order of the area they cover on the island.

Tinta Negra

This red grape is the most planted grape variety on the island by far, with 277 hectares in 2010. Also planted on the Canaries, it is by no means the oldest variety and was probably introduced to Madeira from mainland Portugal in the eighteenth century. Red grapes being much less common at the time, it simply went under the name Tinta (although wines may also have included the poorer quality red Maroto) until the early nineteenth century, when the name Negra Mole (soft black) was added. Occasionally bottles of madeira labelled Tinta can still be found. The name was officially truncated to Tinta Negra by the Instituto da Vinha e do Vinho in Lisbon in 2000.

Next page