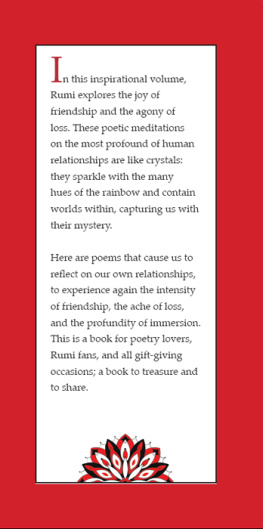

This book is for all those who

This book is for all those who

love what Rumi and Shams love.

Contents

R UMI s L IFE Jelaluddin Rumi was born near the city of Balkh in what is now Afghanistan, then on the eastern edge of the Persian Empire, on September 30, 1207. He descended from a long line of Islamic jurists, theologians, and mystics. When Rumi was still a young man, his family left Balkh ahead of the invading armies of Genghis Khan, who was extending his empire westward, eventually all the way to the Adriatic. It is said that Rumis father, Bahauddin, loaded ninety camels with just books for the journey. Theirs was a profoundly learned lineage.

Rumi and his family went to Damascus and on to Nishapur, where the poet and teacher Fariduddin Attar recognized the teenage boy as a great spirit. He is reported to have said, as he saw Bahauddin walking toward him with Rumi a little behind, Here comes a sea, followed by an ocean. To honor this insight he gave Rumi a copy of his wonderful Ilahinama ( The Book of God ). The family eventually settled in Konya, now in south-central Turkey, where Bahauddin resumed his role as head of the medrese , the dervish learning community. Rumi was still in his twenties several years later when his father died and he became head of the medrese. He gained a wide reputation as a devout scholar, and his school reportedly numbered over ten thousand students.

Broadly speaking, the work of Rumis community was to open the individual and the collective heart. Its members used music and poetry and movement. They sat in silence. They listened to discourses. Stories, jokes, meditationeverything was used. (The cook Ahim Baaz was a very important figure in Rumis community. (The cook Ahim Baaz was a very important figure in Rumis community.

You can visit his tomb in Konya today.) The members of Rumis community walked together. They worked in the garden and the orchard. They observed animal behavior very carefully; it was a kind of scripture they read for signs. This was not a renunciate group. Everyone had a family and a line of useful work; they were masons, grocers, weavers, hatmakers, carpenters, tailors, and bookbinders. Everyone was deeply engaged.

These were affirmative, ecstatic makers. Some call them Sufis. I like to say they were living the way of the heart. A few years after Bahauddins death in 1231, Burhan Mahaqqiq, a hermit meditator in the remote mountain region north and east of Konya, returned and found that his teacher, Rumis father, had died. He decided to devote the rest of his life to training his teachers son. For nine years he led Rumi on many, sometimes three consecutive, forty-day fasts ( chillas ).

Rumi became a joyful adept in this mystical tradition. Rumis oldest son, Sultan Velad, saved 147 of his fathers personal letters, so, amazingly, we have a somewhat accurate sense of what his daily life was like eight centuries ago. He was deeply involved in the details of community life. In one letter he begs a man to put off, for fifteen days, collecting the money he is owed by another man. In another he asks a wealthy nobleman to help a student out with a small loan. Someones relatives had moved into the hut of a devout old woman, and he tries to solve the situation.

Sudden lines of poetry are scattered throughout the practical business contained in the letters. His life was grounded in daily necessities and in the ecstatic simultaneously. In the late fall of 1244, Rumi met Shams Tabriz, a fierce man-God, or God-man. Shams had wandered through the Near East in search of a soul friend on his level. Shams was sometimes lost in mystical awareness for three or four days. He took work as a mason to balance his visionary bewilderment with hard physical labor.

When he was paid, he contrived to slip his wages into another workers jacket before he left. He never stayed anywhere long. Whenever students began to gather around him, as they inevitably did, he excused himself for a drink of water, wrapped his black cloak around himself, and was gone. Because of this restless searching, he was known as Parinda , or the Flier or Bird. He prayed that Gods hidden favorite be revealed to him, so that he could learn more about the mysteries of divine love. An inner voice came, What will you give in return? My head, said Shams.

The one you seek is Jelaluddin of Konya, son of Bahauddin of Balkh. Shams arrived in Konya on November 29, 1244. He took lodging at the caravanserai of the sugar merchants, pretending to be a successful seller of sugar. But all he had in his room was a broken water pot, a ragged mat, and a headrest of unbaked clay. One day, as Shams sat at the gate, Rumi came by riding a donkey, surrounded by students. Shams rose and took the bridle.

Money changer of the current coins of esoteric significance, knower of the names of the Lord, tell me. Who is greater, Muhammad or Bestami? Muhammad is incomparable among the saints and prophets. Then how is it he said, We have not known You as You should be known, while Bestami cried out, How great is my glory! Rumi fainted when he heard the depth of the question and fell to the ground. When he revived, he answered, For Muhammad the mystery is always unfolding, while Bestami takes one gulp and is satisfied. The two tottered off together. They spent weeks and months at a time together in the mystical conversation known as sohbet .

Another version of their meeting is: One day Rumi was teaching by a fountain in a small square in Konya. Books were open on the fountains ledge. Shams walked quickly through the students and pushed the books into the water. Who are you and what are you doing? Rumi asked. You must now live what you have been reading about. Rumi turned to the books in the fountain, one of them his fathers precious spiritual diary, the Maarif.

Shams said, We can retrieve them. They will be as dry as they ever were. He lifted out the Maarif to show him. Dry. Leave them, said Rumi. With that relinquishment of books and borrowed awareness, Rumis real life began, and his real poetry too.

What I had thought of before as God, Rumi said, I met today in a human being. The meeting with Shams was the central event in Rumis life. They were together in Konya for about three and a half years. Twice during that time the jealousy of Rumis disciples drove Shams away, and twice Rumi sent his son Sultan Velad to bring him back. What happened next is the subject of extensive debate among scholars. Shams either left on his own, disappearing without a trace, as he had evidently threatened several times to do, or was killed by a group of the jealous disciples, including one of Rumis sons, Ala al-Din.

The latter is the version that has come down in the oral tradition among the Mevlevi dervishes, the order begun by Sultan Velad. In this version Shams came to Sultan Velad in a dream after he had been killed and told him the circumstances of the murder. The son then kept that painful information from Rumi. He let him go out on long searches for Shams, to Damascus and elsewhere. The situation became a kind of reverse analogue for the Joseph story, in which Josephs brothers pretend that the beloved one is dead, telling Jacob, the father, that he has been killed by a wolf. Here Rumi is not told that the beloved one has been killed by a group of his students, one of them his son.

Both stories involve the central figure living for years under a misconception about the person dearest to them. The Joseph story, of course, resolves beautifully when Joseph, through his dream-interpreting skills, comes to be in charge of the granaries of Egypt and then later reunites with his family. Rumi is reunited with Shams in the poetry, and in his inmost core. Perhaps a conventional religious community cannot contain the wild originality of a Shams Tabriz until it becomes embodied in someone like Rumi, who can be a bridge between wild gnostic experience and more traditional belief. This mysterious event comes on one of Rumis journeys in search of Shams. Suddenly, walking a Damascus street, Rumi feels that he is their friendship, that he no longer needs to look for Shams.

Next page

This book is for all those who

This book is for all those who