C ontents

For Ann Cornelisen

A cknowledgments

Many thanks to my agent, Peter Ginsberg, of Curtis Brown Ltd., to CharlieConrad, my editor at Broadway Books, and to the spectacular staff at Broadway Books. Jane Piorko of the New York Times, Elaine Greene of House Beautiful, and Rosellen Brown, guest editor of Ploughshares, published early versions of parts of this book: mille grazie. Friends and family members deserve at least a bottle of Chianti and a handful of Tuscan poppies: Todd Alden, Paul Bertolli, Anselmo Bettarelli, Josephine Carson, Ben Hernandez, Charlotte Painter, Donatella di Palme, Rupert Palmer, Lyndall Passerini, Tom Sterling, Alain Vidal, Marcia and Dick Wertime, and all the Willcoxons. Homage to the memory of Clare Sterling for the gift of her verve and knowledge. To Ed Kleinschmidt and Ashley King, incalculable thanks.

P reface

WHAT ARE YOU GROWING HERE? the upholsterer lugs an armchair up the walkway to the house but his quick eyes areon the land.

Olives and grapes, I answer.

Of course, olives and grapes, but what else?

Herbs, flowerswe're not here in the spring to plantmuch else.

He puts the chair down on the damp grass and scans thecarefully pruned olive trees on the terraces where we now areuncovering and restoring the former vineyard. Grow potatoes, he advises. They'll take care of themselves. He points to the third terrace. There, full sun, the right place for potatoes, red potatoes, yellow, potatoes for gnocchi di patate.

And so, at the beginning of our fifth summer here, wenow dig the potatoes for ourdinner. They come up so easily; it's like finding Easter eggs. I'm surprised how clean they are. Just a rinse and they shine.

The way we have potatoes is the way most everything has come about, as we've transformed this abandoned Tuscan house andland over the past four years. We watch Francesco Falco, who has spentmost of his seventy-five years attending to grapes, bury the tendrilof an old vine so that it shoots out new growth. We do the same.The grapes thrive. As foreigners who have landed here by grace,we'll try anything. Much of the restoration we did ourselves; anaccomplishment, as my grandfather would say, out of the fullness ofour ignorance.

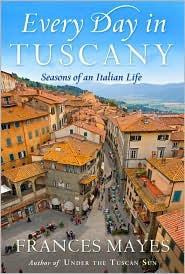

In 1990, our first summer here, I bought an oversized blankbook with Florentine paper covers and blue leather binding. On thefirst page I wrote ITALY. The book looked as though it should haveimmortal poetry in it, but I began with lists of wildflowers, lists ofprojects, new words, sketches of tile in Pompeii. I described rooms,trees, bird calls. I added planting advice: Plant sunflowers whenthe moon crosses Libra, although I had no clue myself as to whenthat might be. I wrote about the people we met and the food wecooked. The book became a chronicle of our first four years here.Today it is stuffed with menus, postcards of paintings, a drawing ofa floor plan of an abbey, Italian poems, and diagrams of the garden.Because it is thick, I still have room in it for a few more summers.Now the blue book has become Under the Tuscan Sun, anatural outgrowth of my first pleasures here. Restoring, thenimproving, the house; transforming an overgrown jungle into itsproper function as a farm for olives and grapes; exploring thelayers and layers of Tuscany and Umbria; cooking in a foreign kitchenand discovering the many links between the food and theculturethese intense joys frame the deeper pleasureof learning to live another kind of life. To bury the grape tendril insuch a way that it shoots out new growth I recognize easily as ametaphor for the way life must change from time to time if we are togo forward in our thinking.

During these early June days, we must clear the terraces of the wild grasses so that when the heat of July strikes and the land dries, we'll be protected from fire. Outside my window, three men with weedmachines sound like giant bees. Domenico will be arriving tomorrowto disc the terraces, returning the chopped grasses to the soil. Histractor follows the looping turns established by oxen long ago.Cycles. Though the weed machines and the discer make shorter work,I still feel that I fall into this ancient ritual of summer. Italyis thousands of years deep and on the top layer I am standing on asmall plot of land, delighted today with the wild orange liliesspotting the hillside. While I'm admiring them, an old man stopsin the road and asks if I live here. He tells me he knows the landwell. He pauses and looks along the stone wall, then in a quietvoice tells me his brother was shot here. Age seventeen, suspectedof being a Partisan. He keeps nodding his head and I know the scenehe looks at is not my rose garden, my hedge of sage and lavender.He has moved beyond me. He blows me a kiss. Bella casa,signora. Yesterday I found a patch of blue cornflowers aroundan olive tree where his brother must have fallen. Where did theycome from? A seed dropped by a thrush? Will they spread next yearover the crest of the terrace? Old places exist on sine waves oftime and space that bend in some logarithmic motion I'm beginningto ride.

I open the blue book. Writing about this place, our discoveries,wanderings, and daily life, also has been a pleasure. A Chinese poetmany centuries ago noticed that to re-create something in words islike being alive twice. At the taproot, to seek change probably alwaysis related to the desire to enlarge the psychic place one lives in.Under the Tuscan Sun maps such a place. My reader, I hope,is like a friend who comes to visit, learns to mound flour on thethick marble counter and work in the egg, a friend who wakes tothe four calls of the cuckoo in the linden and walks down the terrace paths singing to the grapes; who picks jars of plums, drives with me to hill towns of round towers and spilling geraniums, who wants to see the olives the first day they are olives. A guest on holiday is intent on pleasure. Feel the breeze rushing around those hot marble statues? Like old peasants, we could sit by the fireplace, grilling slabs of bread and oil, pour a young Chianti. After rooms of Renaissance virgins and dusty back roads from Umbertide, I cook a pan of small eels fried with garlic and sage. Under the fig where two cats curl, we're cool. I've counted: the dove coos sixty times per minute. The Etruscan wall above the house dates from the eighth century B.C. We can talk. We have time.

Cortona, 1995

B ramare:

(Archaic) To Yearn For

I AM ABOUT TO BUY A HOUSE IN A FOREIGN country. A house with the beautiful name of Bramasole. It is tall, square, andapricot-colored with faded green shutters, ancient tile roof, and aniron balcony on the second level, where ladies might have sat withtheir fans to watch some spectacle below. But below, overgrownbriars, tangles of roses, and knee-high weeds run rampant. Thebalcony faces southeast, looking into a deep valley, then into theTuscan Apennines. When it rains or when the light changes, thefacade of the house turns gold, sienna, ocher; a previous scarletpaint job seeps through in rosy spots like a box of crayons leftto melt in the sun. In places where the stucco has fallen away,rugged stone shows what the exterior once was. The house risesabove a strada bianca, a road white with pebbles, on a terraced slab of hillside covered with fruit and olive trees.Bramasole: from bramare, to yearn for, and sole, sun: something that yearns for the sun, and yes, I do.

Next page