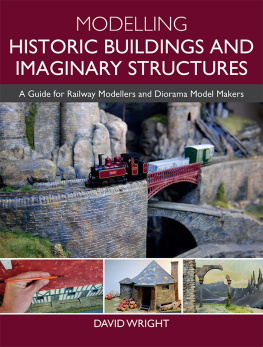

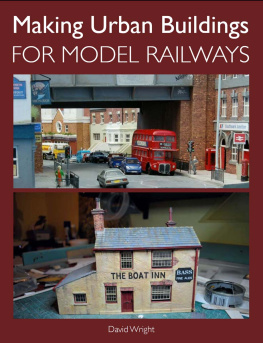

APPENDIX III

ROOFS

A Brief History of Keeping the Rain Out

At the dawn of railways, thatch was the standard cheap roofing material. The most substantial properties tended to use solid stone for roofing, where it was available, and hand-formed clay tiles where it wasnt. Stone slabs got smaller over time, moving from locally sourced large slabs, through gradually smaller stone-slate, to pure slate. This was first commercially cut in north Wales around 1820, distributed initially by sea and then, much more widely, by the railways. Later still, machine-made tiles appeared and were generally quicker to fit important as labour costs increased and nowadays are so widely used that real stone, thatch and reclaimed period tiles are considered luxury end roofing materials.

Although railway modelling has continued happily despite the passing of the steam age, roof coverings devised since then are both well-known and easy to find if you want to model them, so they are not covered here. Perhaps another time

THATCH

When we think of a thatched cottage, most of us have an idea of what one looks like but, as with everything else man-made, there is a surprising number of variations for so simple an idea as bundling up some form of soft, natural material and pegging it down to form a roof. Where once wheat straw was commonly used, the short varieties bred these days for combine harvesting are useless for thatching and with reed and long-straw thatching tending to remain in specific areas where it was once traditional, both wheat-straw and long-straw thatchers now often grow their own, older-type varieties just for thatching. Also note that today, as ever, there are many different cultivars of thatching straw, each with implications of cost, longevity, style and colour for the finished work. Indeed, some caps or ridges (different names for the same thing) are made of different straw to the rest of the roof while, because most caps are replaced more often than the main roof, even using the same straw type can lead it to exhibit much less weathering and therefore to noticeably different colourings. As for precise details, you would have to ask an expert: I am merely an observer of the finished works.

The simplest of all thatches to model: flat, plain cap, with ends hidden by elevated masonry gables. (The grainy effect is not pixellation but a covering of chicken wire, used today to protect the straw from vermin and birds wanting nesting materials.)

Here the thatch overshoots the gable end forming broad shoulders separated by a protruding chimney. Unusually, it has been trimmed short around a slated gable.

This lateral gable has its verges joined by a flush, rounded cap, which is formed into a point at the top.

More commonly, thatched gables have a half-hipped rounded ridge end, as on this barn.

Full hips are quite common too: note also the narrow slated strip between these two adjacent (and very grey), long-straw thatches.

Two contiguous combed wheat thatches of similar age at a property boundary: note the subtlely different treatments, probably indicating work by different thatchers.

North-facing thatch among trees can accumulate a lot of green lichens. Note the exaggeratedly pointed end to the cap.

The very slight edge to this cap (shallow blocking), is a notable feature of this decidedly brown thatch. It would seem theres a prototype for my model after all!

With each thatch taking a skilled man several weeks to complete, even with a helper, there were once hundreds perhaps thousands of working thatchers around the country, each one producing work which would have been individually recognizable to another local thatcher. Sadly, with a useful life of between but twenty to fifty years, few, if any, of the top coats we see in pre-war period photos are likely to have survived this long. However, good thatchers today have nurtured those early skills and, travelling much further afield for jobs than they used to, are thus distributing their styles and practices more widely than was once the case, although English Heritage and most councils try very hard to retain local thatching characteristics. Even so, a single village (if of sufficient size and amply thatched), can sometimes offer the curious a lot of variations to study. Here I first present some of the variety I found around just two Dorset villages, Piddletrenthide and Broadmayne, and then I offer examples from elsewhere for comparison, leaving the reader to study the particular local period traditions in their own area of interest.

A much paler, almost fawn-coloured cap sits here above a browny-grey thatch.

This old thatch has been around for a while and lost about half of its cross rods. See how the lower edge (eave), takes no account of the window; then note also the subtle yealm edges every nine inches or so down the face of the roof, highlighted in places by the moss, suggestive of a long-straw roof.

Notable features here are: the cross rods or pattern pieces (the diagonals between the horizontal liggers) are much more numerous and closer together than hitherto; the cap end is formed into a ridge peak (like a focsle on a ship); the windows are denoted by vestigial raised arcs (eyebrows); and we see a thatchers signature two long-tailed straw birds facing each other.

Here, not only do we have deeper eyebrows over the windows but they are formed using slightly raised sections, almost dormers but not quite. Note too, the sparse cap decoration of a single point (far) and a single club or trefoil (near). The grey colour indicates a wheat thatch (reed thatches turn a deep golden-brown with age), while the fur-like finish shows this to be a combed wheat thatch, in which the stalks are shut neatly together using a biddle or beater so that only their ends show.

Next page