RAILWAY ARCHITECTURE

Bill Fawcett

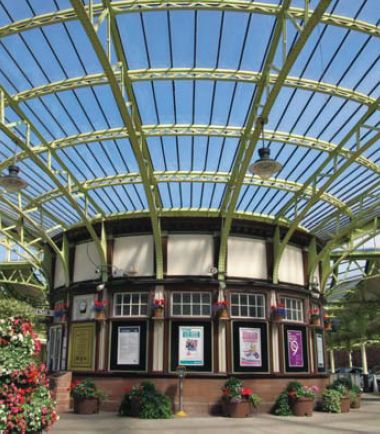

Wemyss Bay station, Renfrewshire (1903), was the Caledonian Railways showpiece railhead for local commuters and its ferry service to the Isle of Bute.

William Hamlyns 1938 concourse at Leeds City station depicted in a British Railways carriage print.

CONTENTS

Middleton Top engine house, Derbyshire, was preserved following closure in 1963 and retains the two-cylinder beam engine supplied in 1829, albeit with many parts renewed. Wagons were hauled up and down the incline on an endless wire rope.

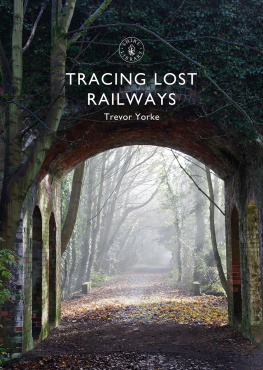

GETTING STARTED

B RITAIN S RAILWAY BUILDINGS evoke the countrys rise as the worlds first great industrial power while also reflecting the architectural currents of their time. Causey Arch in County Durham (1727) reminds us that railways derived from wooden-railed, horse-drawn wagonways, generally carrying coal and stone, but between 1790 and 1830 they evolved into major public carriers using iron rails and steam locomotives, and requiring specialised buildings.

The Stockton & Darlington Railway (September 1825) demonstrates this. At first its locomotives hauled only coal and mineral trains while contractors employed horses for other goods and passengers. Operational buildings were confined to toll houses, workshops, and engine houses both for locomotives and for the winding engines providing rope haulage over the Brusselton and Etherley Ridges. After a year, the goods and passenger traffic justified the company building a warehouse at Darlington, along with inns for waiting passengers, at Stockton, Darlington and Heighington. The last included an agents office and is the oldest surviving building at any operational station, though no longer used by the railway. Only a fragment remains of the Brusselton incline engine house but the Cromford & High Peak Railway (now a country trail) in Derbyshire retains one at Middleton Top (1830), as well as a transhipment warehouse (1832) at Whaley Bridge. Darlingtons North Road Museum conserves the Stockton & Darlingtons 1833 goods station and 1842 passenger station.

Causey Arch near Stanley, County Durham, was built in 1727 for the Tanfield wagonway. Its 32-metre span, then the largest stone arch in Britain, emphasises the profitability of some early wagonways.

Formal station buildings originated with the Liverpool & Manchester Railway (1830), which provided these at its termini though not, for some years, at wayside stops. Its Manchester station survives as a museum. A low brick viaduct sandwiched between this and the goods warehouse bore trains at first-floor level. First- and second-class passengers were segregated throughout, with separate entrances, booking halls and stairs up to the waiting rooms and platform. Cross-walls divided the warehouse into compartments served by branch tracks at right angles to the running line, wagons being swung into these on hand-operated turnplates.

Stockton Toll House, seen around 1970 before the tracks were taken up, was one of three designed by John Carter in classic turnpike fashion. Each had a wagon-weighing machine so that the appropriate toll could be calculated.

Whaley Bridge, Derbyshire. Integrated transport: the warehouse provided shelter for transhipment between a branch of the Peak Forest Canal and flanking railway tracks that entered through the two big arches.

Early passenger carriages required covered storage, so the Manchester station was quickly extended to provide a carriage shed reached via turnplates, with retail units below; the resulting street frontage resembles a row of houses. The Liverpool terminus has vanished but had a platform canopy, soon augmented by a wooden carriage shed over the main tracks, forming a prototype for the trainsheds that came to epitomise major stations.

Newtyle station (18312), formerly served by a railway from Dundee, is another early survivor a goods shed with passenger platform at one end. The oldest remaining passenger trainshed is at Selby (1834), terminus of a line from Leeds and transfer point for river steamers to Hull; this was roofed in three spans, with the passenger station in the middle and goods either side. The transfer of passengers to new premises (1841) ensured its survival as a goods station and now private warehousing.

Manchester Liverpool Road terminus, now the Museum of Science and Industry; on the left is the passenger station, with the carriage shed at this end; the goods warehouse is on the right.

The Euston entrance screen (Philip Hardwick). The portico led into a courtyard with the station on the right and a vacant plot opposite, originally intended for the Bristol line (Great Western) terminus. The station soon expanded into all this space.

Rich, proud Liverpool brought the next progression in passenger termini. In 1836 the station moved to Lime Street, opposite the Plateau, earmarked as a civic forum. For the first time a station would become a townscape feature, so the council funded a neo-classical screen to platforms and trainshed. There were two platforms: one for departures, flanked by waiting rooms and offices, and one for arrivals, flanked by a cab road. This set the pattern for termini for years to come.

Hard on Liverpools heels came Londons Euston station (18378, demolished), serving Robert Stephensons Birmingham line, one of the first trunk railways. It featured a frontal screen with a giant Doric portal, but equally significant was the two-span trainshed, which pioneered the railway use of a light wrought-iron truss, based on developments in workshop and warehouse roofs. Euston trusses became widely popular, and their early character can still be appreciated in Scarborough station (1845).

Northumberland has the oldest surviving engine shed: Greenhead (1836), a long narrow building, later used for road vehicles. This form remained commonplace but others developed alongside, notably the roundhouse, which held engines stabled on spur roads radiating from a turntable. Few roundhouses remain in Britain, and none are in railway use, but they include an early example at Derby (1840) by Stephenson and his architect, Francis Thompson. Along with contemporaneous workshops and offices, it has been conserved under the name Pride Park. Chalk Farm in London retains the 1847 roundhouse that served Euston, and is now a well-known arts venue, while Leeds (Holbeck) has two: a stylish twenty-two-road shed (1850) with an open turntable encircled by a stone arcade, and a half roundhouse of 1864. The latter form was unusual in Britain but common in Germany, where a number remain in operation.