Contents

Guide

CONTENTS

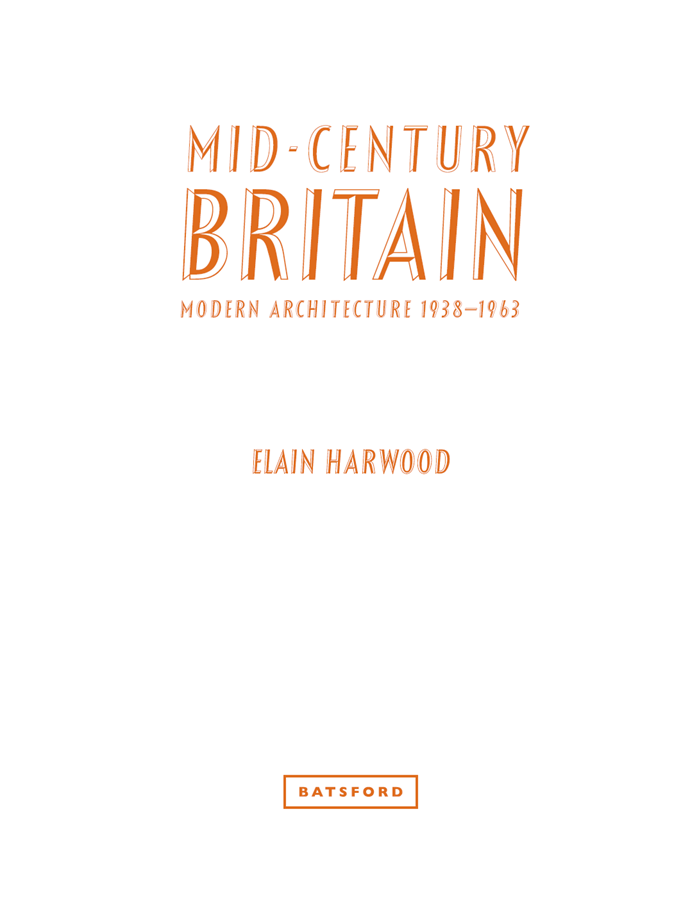

MID-CENTURY BRITAIN

Mid-century modern is a term coined in the United States to describe architecture and design from about 1940 to the early 1960s. Used only a little during that period, it became popular when in 1984 Cara Greenberg published Mid-Century Modern: Furniture of the 1950s, an example of the design world taking the lead in reviving a fashion and bestowing its nomenclature as it had with Art Deco. The name was quickly adopted to describe the flash hotels built along Miamis northern shore in the 1940s and 1950s, and as quickly reduced to Mi-Mo, also referring to Miami Modern.

British architects around 1950 had their own terminology. They spoke instead of the New Empiricism or New Humanism to describe a gentle modernism that was simple and functional but had decorative touches. In calling her ground-breaking survey Contemporary, in 1994 Lesley Jackson revived a name used in its day for buildings and interiors considered to lack intellectual rigour, usually well-meaning public buildings designed by junior borough architects with too many contrasts of materials, colours and planes. When I hear the word contemporary, I reach for my revolver, quipped Theo Crosby in a manifesto for the counter-movement, the New Brutalism. What he would have made of the term Soft Brutalism used today for much of this architecture should perhaps remain unprinted. Mid-century modern might be American, but it usefully describes the best design by a generation that was equally confident in architecture, furniture design and landscape, which included such international talents as Arne Jacobsen, Alvar Aalto, Eero Saarinen, Charles and Ray Eames and Marcel Breuer. Yet the phrase can equally be used of more modest but dynamic symbols of post-war affluence such as cafs and ice-cream parlours. There is (inevitably) a more specific American term for this the Googie style, taken from the coffee shop of that name in Hollywood designed by John Lautner in 1949 and used by Douglas Haskell of House & Home magazine in 1952 to describe the futuristic shapes, day-glo colours and neon synonymous with the diners, motels and drive-ins of suburban highways. Planning legislation and limited car ownership, especially among the young, ensured such developments remained rare in Britain; a motel built at Newingreen, Kent, in 1952 was listed, yet was demolished.

One name truly describes the architecture and design of the 1950s in Britain, and Britain alone: the Festival style, a reference to the great exhibition of British culture and manufactures held across the country in the summer of 1951. It marked the evolution of modernism in a country where neo-classicism and Art Deco styles had dominated public building through the 1920s and 1930s. These had adopted many details from northern Europe, particularly Scandinavia, and so too did the gentle modernism beginning to be seen by the Second World War. If the Festival of Britain marked the high point of this styles fashionability, it remained the dominant style into the early 1960s, surviving longest in libraries, town halls and entertainment buildings. Elsewhere it began to be refined, to become more measured and simple in its ingredients, reaching a minimal extreme with the development of curtain walling whole facades of glass, aluminium and steel. Mid-century modern embraces all these variants. First of all, though, the use of the word modern requires some extra explanation, taking us back further in time.

The Modern Movement

Britain saw little in the 1920s of modernism, the radical style epitomised by white boxes of reinforced concrete. It need not have been so, for the country had made early advances in concrete as well as steel-framed construction, just as its Arts and Crafts movement had looked for simplicity in the use of traditional materials and furnishings. Indeed, in his book on modernism first published in 1936, Nikolaus Pevsner claimed William Morris as its first pioneer. Nevertheless, it would be possible to write a parallel account of early 20th century architecture in the English-speaking world, especially the United Kingdom, which focused solely on classical buildings. A genre harking back to the traditions of Sir Christopher Wren seemed suited to the head of the worlds largest empire and responded to building regulations that favoured conservative construction methods; it was encouraged by the importation of Beaux-Arts doctrines from France to the growing schools of architecture, notably at Liverpool University, which in 1894 introduced the first course to be recognised by the Royal Institute of British Architecture (RIBA).

In the 1920s British architects found inspiration in northern Europe and especially Scandinavia. Denmark and Sweden also followed a broadly neo-classical tradition at this time, with Philip Morton Shand coining the phrase Swedish Grace to describe the stripped-back refinement found in that country. Its builders developed distinctive brick bonds and diaper patterns, projecting headers being a particular favourite, which they combined with render and coloured tiles. Monopitch roofs were practical in heavy snowfalls. The Netherlands offered an extensive range of more modern housing models, from low-rise estates by J.J.P. Oud to tall flats by Johannes Brinkman and Willem van Tijen; Philip Powell and Hidalgo Moya used their student prizes to visit Rotterdam in 1945 ahead of designing Churchill Gardens. Willem Dudoks new town of Hilversum became a source for many public buildings. Herbert Tayler knew the Netherlands through his Dutch mother, but was also impressed by Ernst Mays working-class terraces in Frankfurt, seen on a student trip with his partner David Green in 1930.

The development of reinforced concrete was taken forward in Europe and then America rather than Britain. The reinforcement of concrete with an embedded steel mesh provided some tensile strength and a greater efficiency in compression, and was first patented in Britain under franchise by a French company, Hennebique. The result in 1897 was an enormous flour mill for Weaver & Co. in Swansea. By 1914, architects in central Europe were showing that steel, glass and concrete could produce industrial architecture of great elegance, exemplified by Gropiuss Fagus Factory at Alfeld near Hanover completed that year. Meanwhile, in Vienna, Otto Wagner, Adolf Loos and others were designing prestigious offices and executive houses without mouldings, producing geometric shapes with sheer planes as facades. After 1918, these clean forms, acknowledging only the basic classical proportions to inform new ways of interspersing solids and voids, suggested a stylish, healthier way of living one without excess or the trappings of past regimes now discredited. This seemingly simple architecture also offered possibilities for cheap housing and a range of public buildings, addressing a social agenda of growing importance as left confronted right in the straitened times that followed the Great War and Russian Revolution.

Housing at Rmerstadt, Frankfurt: Ernst May, 1928.

Bauhaus, Dessau: Walter Gropius, 1924.