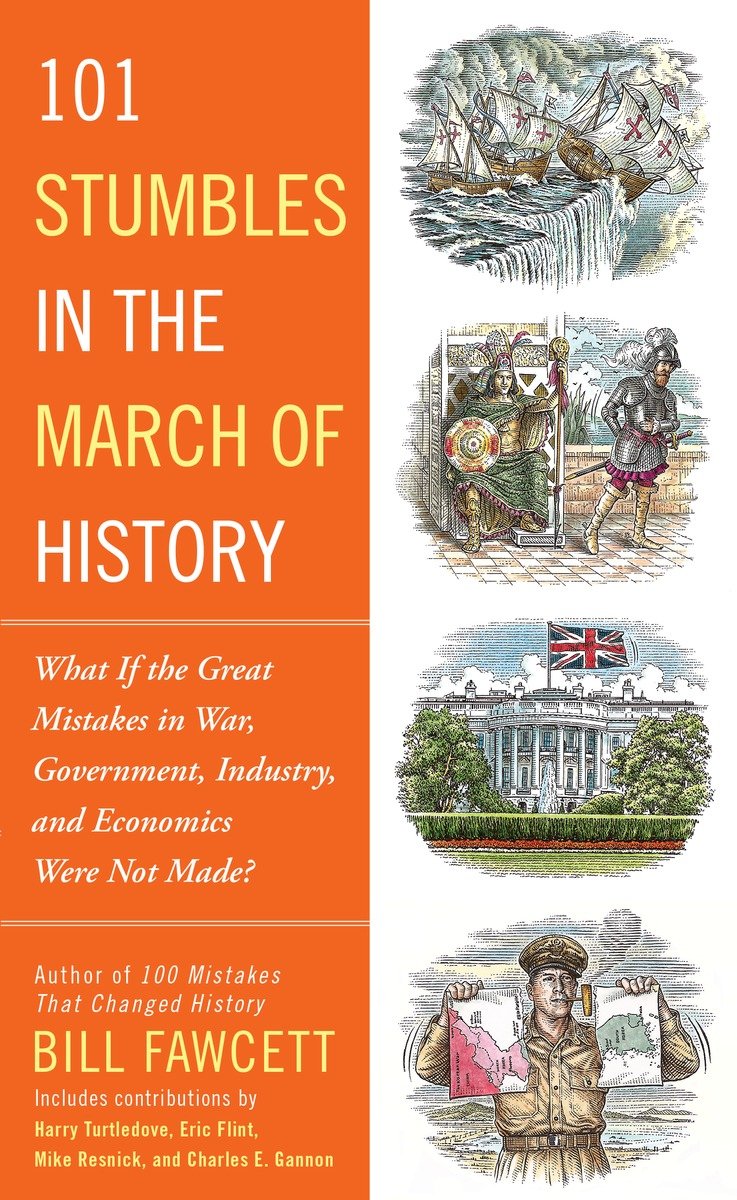

NEW AMERICAN LIBRARY

Published by Berkley

An imprint of Penguin Random House LLC

375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014

Copyright 2016 by Bill Fawcett & Associates, Inc.

Penguin Random House supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to continue to publish books for every reader.

New American Library and the NAL colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Fawcett, Bill, author.

Title: 101 stumbles in the march of history: what if the great mistakes in war, government, industry, and economics were not made?/Bill Fawcett.

Description: New York: NAL, New American Library, [2016]

Identifiers: LCCN 2016012531 | ISBN 9781101987049 | 9781101987056 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: World historyMiscellanea. | ErrorsHistory. | Imaginary histories.

Classification: LCC D24 .F39 2016 | DDC 909dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016012531

Jacket illustrations by Dave Hopkins

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers and Internet addresses at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

Version_1

INTRODUCTION

T he march of history is really more like a drunkards rambling walk. No matter what the wisest and most powerful leaders carefully plan, history has a habit of going its own way. Communism falls and Russia is on a vector for democracy with the West cheering; then Putin arrives. The US and allies invade Iraq, but stop short of Baghdad, then do it again and finish the job so that it seems all is well; then we pull out and it isnt, and ISIS rises. If history has a consistent theme, it might be that nothing goes as planned. One of the reasons for this is that people make history, and men and women make mistakes. Those miscalculations and omissions are the potholes that history stumbles in and that cause it to change direction as it lurches ahead into the unknown.

With the benefit of 20/20 hindsight, this book, in ninety-six articles, looks at 101 mistakes that were made in times and places ranging from ancient Persia to modern Washington, DC. A hundred and one blunders that in each case helped divert the course of history. Some errors created disasters, some changed how we all think or feel, and a few even benefited mankind. We end many of our looks at these world-changing blunders by speculating on what your life today might be like if those mistakes had not been made.

1

EARTH AND WATER, A MISUNDERSTANDING

490 BCE

By Bill Fawcett

What we have here is a failure to communicate.

T his book begins with a situation where a politician caused a war that changed the world. It ends with another example of the same thing. Both even deal with the spread of democracy.

Greece in the fifth century BCE was made up of dozens of independent city-states. Two of the greatest, Athens and Sparta, were close to war. Athens feared defeat from the much more warlike Spartans and searched for an ally that would discourage their enemy from even attacking. They soon realized that there was really only one power so great that even Sparta would have to hesitate. This was the Persian Empire, ruled by Darius.

Now, the Athenians already had a dubious relationship with Darius and his empire. Ten years earlier, they had sent an army to support a revolt by one of their former colonies that had been absorbed by Persia decades earlier. The revolt never had a chance, but the combined army of Athens and two other Greek cities did succeed in almost conquering the capital of the Persian state (known as a satrapy), the city of Sardis. They managed to capture all of the city except the central fortress, where the Persians were still resistingwhen a large relief army approached. The Athenians burned Sardis before hurriedly withdrawing. It was an insult made even stronger by the fact that the ruler of the satrap of Sardis was Dariuss brother-in-law.

So when these same Athenians appeared a decade later, looking for an alliance, they were informed that Persia would protect them only if an offering of earth and water was made to Darius and Persia. It seems that the Athenians, anxious for support, did not check out exactly what this meant. There were many ceremonies sealing alliances with pledges before the gods within Greece itself. They may have thought this was just another version of that. They probably did not realize that this particular offering involved a pledge of fealty and obedience to Persia forever by Athens and all her citizens. By doing this, Athens was, in the eyes of the Persians, joining the Persian Empire and acknowledging Darius as its emperor. Or perhaps the members of the Athenian delegation were so desperate that they accepted or ignored the meaning of the demand. So, through their ambassadors, Athens swore an oath of earth and water to Darius. Considering all the problems Athens had caused Darius before, it is not surprising he demanded a high price for his support.

The delegation had not even been back in Athens long enough for the promised Persian support to follow when the Spartans hurried to attack. To the amazement of both sides, Athens met them in battle outside the city and drove off the Spartans. The threat ended, Athens sent a message to the Persians that their aid was not needed and the deal was off. But you just did not pledge, then take away, your allegiance to a Persian emperor. You certainly did not do this if you were just a small city-state that was hundreds of times smaller than their empire. More so since you had already earned the emperors enmity. It was by Persian standards a supreme insult. To them, Athens had agreed to be part of their empire and then was in revolt before the ink dried.

This misunderstanding initiated more than a century of warfare. Where the Greek cities had been basically ignored by the Persians, now their destruction and incorporation into the empire became an imperial priority. The resulting wars strained all the Greek city-states. The first battle resulting from the Persians sending an army to claim Athens, which they felt was theirs, led to a Persian defeat at the Battle of Marathon in 490 BCE. Dariuss son Xerxes invaded with a massive army and fleet seeking revenge for the Athenian insult and perfidy, but was defeated finally at Salamis. That Greek victory came too late to save an evacuated Athens from being burned by the Persians, possibly in direct revenge for their burning of Sardis. The conflict was only settled a century later when a united Greece, in the form of Macedonia and Alexander the Great, turned the entire dynamic around and conquered Persia.

![Fawcett - How to lose the Civil War : [military mistakes of the War between the States]](/uploads/posts/book/92687/thumbs/fawcett-how-to-lose-the-civil-war-military.jpg)