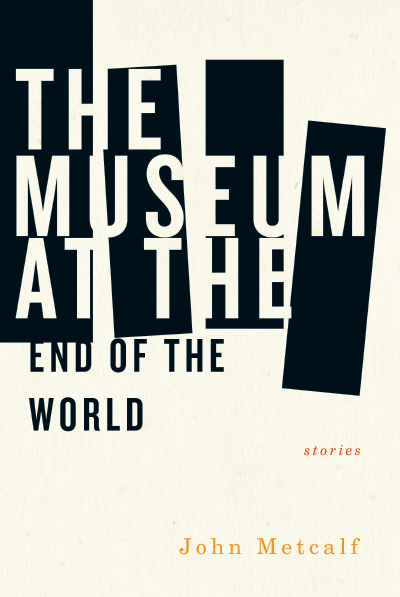

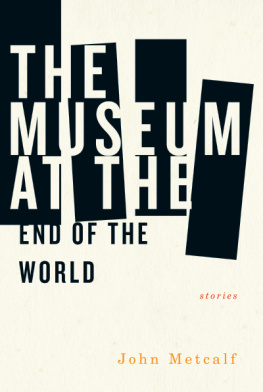

The Museum at the End of the World

The Museum at the

end of the World

JOHN METCALF

BIBLIOASIS

WINDSOR, ONTARIO

Copyright John Metcalf, 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher or a licence from The Canadian Copyright Licensing Agency (Access Copyright). For an Access Copyright licence, visit www.accesscopyright.ca or call toll free to 1-800-893-5777.

FIRST EDITION

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Metcalf, John, 1938-, author

The museum at the end of the world / John Metcalf.

Short Stories

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-1-77196-162-2 (bound)

ISBN 978-1-77196-107-3 (paperback).--ISBN 978-1-77196-108-0 (ebook)

I. Title.

PS8576.E83M88 2016 C813.54 C2016-901846-6

C2016-901847-4

Edited by Daniel Wells

Copy-edited by Emily Donaldson

Typeset by Chris Andrechek

Cover design by David Drummond

Published with the generous assistance of the Canada Council for the Arts and the Ontario Arts Council. Biblioasis also acknowledges the support of the Government of Canada through the Canada Book Fund and the Government of Ontario through the Ontario Book Publishing Tax Credit.

Myrnas

Who would have thought my shrivelled heart

Could have recovered greenness? It was gone

Quite underground; as flowers depart

To see their mother-root, when they have blown;

Where they together

All the hard weather,

Dead to the world, keep house unknown.

And now in age I bud again;

After so many deaths I live and write;

I once more smell the dew and rain,

And relish versing. Oh, my only light,

It cannot be

That I am he

On whom thy tempests fell all night.

(Stanzas from The Flower.

George Herbert, 1633.)

Medals and Prizes11

Ceazer Salad177

Lives of the Poets203

The Museum at the End of the World321

MEDALS AND

PRIZES

Where the Yazoo

Cross the Yellow Dog

Jimbo Palmer and Rob Forde were both fourteen, with Jimbo some months older than Rob. Jimbos mother was warm and friendly but ineffectual. She remonstrated by saying in a trailing-off voice, Now, James or Really, James She made nice sandwiches. Jimbo was quite fond of her but said that hed only give it two or three more years before they carted her off to the loony bin. She washed things a lot in the washing machine and her blonde hair clung darkened to her face but she was still elegant and she often smelled of TCP and her high cheekbones gave her a gaunt beauty, and, though mad, had, Rob thought, distinct sexual possibilities. Had it not been for, being realistic about it, had it not been for her evangelical fervour, the spirit moving in her to request casual callers, the grocers boy, the postman with a parcel, to kneel with her in prayer.

Jimbos stepfather, a retired army officer, was older than Jimbos mother, a bristly, abrupt, bark-y man, uncommunicative, wrapped in a silence that spread uncomfortableness around him. He had a smudge moustache and kept a Webley revolver and a box of bullets in his socks-and-underwear drawer. When not wearing a regimental tie, he affected a foulard.

The Majors breakfast never varied, a three-and-three-quarter minute boiled egg served in a brightly coloured egg cup shaped like a cockerel, a slice of Hovis toast with unsalted butter accompanied by a small cut-glass dish of jam he sometimes called preserve and sometimes confiture . The cut-glass dish sat on a miniature silver salver-thing on which also lay a special silver spoon, smaller than a teaspoon, for spooning up a dollop of jam onto the Majors plate but why he couldnt just

I view hot toast, he said, in one of his rare communications, pointing to the solitary Hovis slice lodged cold in the silver toast-rack, as offensively American.

He had once lowered the pink barricade of the Financial Times and tapped his wristwatchs leather strap and said, Camel.

After breakfast, he and his attach case departed for the City.

Jimbo referred to him as Double-U or Dub, short for Wind-Up Man. In their flights of invention, their badinage, their cherished embroideries, the Key in the centre of the Majors back had a milled shaft

No, no, not milled, you total ape

baboons arse

its knurled, smegma, knurled

They shared their pleasures in his peculiarities while in his presence by rubbing thumb over forefinger in a gesture of watch-winding. Both boys thought of him as an escapee from The Goon Show, an avatar of Major Bloodnock. No more curried eggs for me! they cried, Quick, Nurse! they called, The screens!

Jimbo had worked out from the hallmarkshe had a handbook of themthat the toast-rack had been made in London in 1921; he was interested in such things and his interest was expanding into Sheffield Plate, pewter, and Britannia Metal. He had found a loupe in a junk shop.

You say, I wonder when it dates from? and Ill say, Pass me my loupe.

The Major had had Jimbo sent away when he was twelve, before he and Rob had met, to a military-flavoured boarding school to cure what he called Jimbos softness; Jimbo had overheard mummys boy and lack of manliness and the weeping. He had been expelled after the first term and said only that the letter had described him as a malign influence. What he had been expected to learn was uninteresting and the people had been utterly preposterous.

Utterly, he repeated.

But what did you do that was malignant?

They loved the word.

I committed infractions, said Jimbo, and showed no remorse.

What infractions?

Mainly, I fomented.

Whats that mean?

O.E.D. said Jimbo, tapping his finger three times on the table. The S.O.E.D. old chap, old boy, old sport, old fellow-my-lad. What? What?

The Majors decanters were kept on the sideboard in the dining room in a mahogany-and-brass cage-thing. The decanters, visible inside the spindles, had silver chains round their necks from which hung little oval silver plaques: Whisky, Sherry, Brandy, Gin.

It prevents theft by the servants, the Major had once remarked as he was unlocking it.

We havent got any servants, said Jimbo.

What? said the Major. What?

Which was his usual response to any reply short of complete agreement or grovelling.

I said, said Jimbo, we havent got

Dont say havent got, said the Major. It is both redundant and ill-bred. Havent will suffice.

Righto, said Jimbo.

Rather dangerously, Rob thought.

This is Victorian. A valuable antique, said the Major, putting the little brass key back in his pocket.

Called?

He stared enquiry at them.

Mmmm?

Rob and Jimbo looked at each other.

No? said the Major.

Jimbo shrugged.

A tantalus. Called a tantalus.

His eyes began to wander as if seeking a way out of this unwonted intimacy.

![Linda Romine - Frommers Nashville & Memphis [2012]](/uploads/posts/book/215328/thumbs/linda-romine-frommer-s-nashville-memphis-2012.jpg)