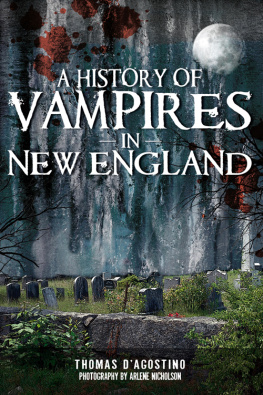

FOOD FOR THE DEAD

FOOD FOR THE DEAD

ON THE TRAIL OF NEW ENGLANDS VAMPIRES

With a new preface by the author

MICHAEL E. BELL

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Middletown, Connecticut

To my parents,

Lester M. Bell and

Sarah Elizabeth Jackson Bell

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Middletown CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

2001 Michael E. Bell

Preface to the Wesleyan paperback edition 2011 Michael E. Bell

All rights reserved

First edition published by Carroll & Graf, 2001

Wesleyan paperback edition, 2011

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by Michael Walters

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011933367

ISBN for the paperback edition: 978-0-8195-7170-0

The poem The Griswold Vampire by Michael J. Bielawa, which appears on pages 176 and 177, was first published in the Summer 1995 issue of Dead of Night. It is reprinted here by courtesy of the poet.

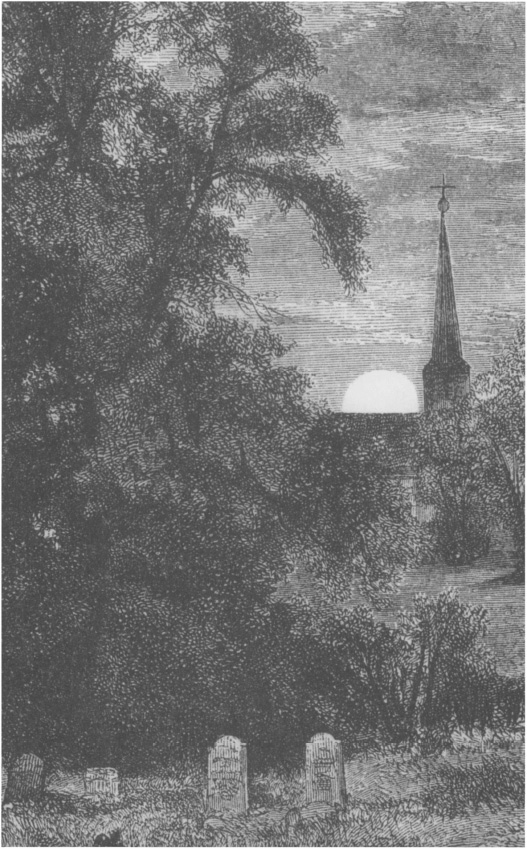

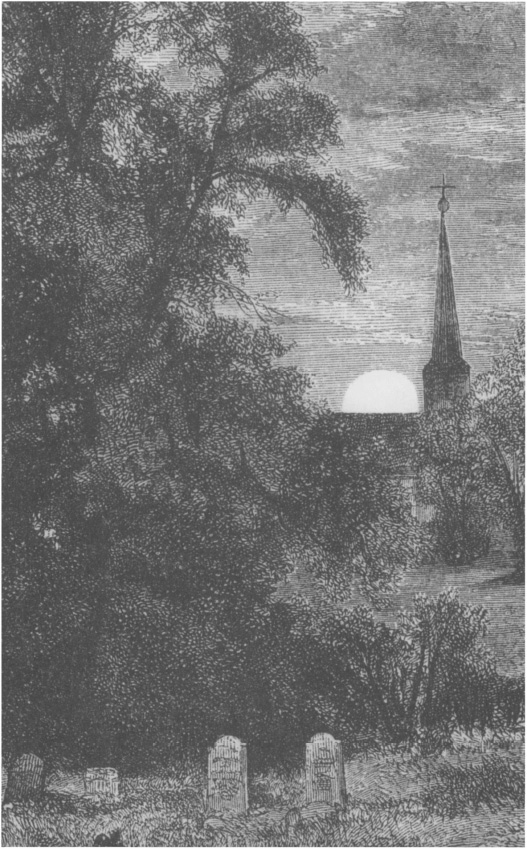

Frontispiece art courtesy Culver Pictures, Inc.

Map of Vampire Incidents in New England (p. xliv) 2001 Jeffrey L. Ward Stonewall illustration by Simon M. Sullivan

5 4 3 2 1

She bloomd though the shroud was around her,

locks oer her cold bosom wave,

As if the stern monarch had crowned her,

The fair speechless queen of the grave.

But what lends the grave such lusture?

Oer her cheeks what such beauty shed?

His life blood, who bent there, had nursd her,

The living was food for the dead!

From the May 4, 1822,

Old Colony Memorial and

Plymouth County (Massachusetts)

Advertiser

CONTENTS

PREFACE TO THE WESLEYAN PAPERBACK EDITION

V ampire. One word, so many images, from Bela Lugosi as Bram Stokers Count Dracula, dressed in tuxedo and cape with hair slicked back, pallid face, prominent canine teeth protruding, to Robert Pattinson as the young, dark, and handsome Edward Cullen of Stephanie Meyers Twilight. But another kind of vampire survived in remote areas of New England more than one hundred years before Stoker penned Dracula in 1897. This book relates my attempt to unravel the mystery of these little-known, so-called vampires. Beginning with a family story told to me by an old Yankee from rural Rhode Island, my search has led me to diverse strands of evidence, including eyewitness accounts, local legends, newspaper articles, local histories, town records, journal entries, unpublished correspondence, genealogies, cemeteries, and actual human remains.

These sources reveal the tragic stories of ordinary farmers confronted with an illness that medicine could neither explain nor cure. This mystifying, fatal disease was consumption, as pulmonary tuberculosis was then called. During the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, New England was in the grip of a terrible tuberculosis epidemic. By 1800, nearly one-quarter of all deaths in the northeastern United States were attributed to consumption, and it remained the leading cause of death throughout the nineteenth century.

Not willing to simply watch as, one after another, their family members died, some New Englanders resorted to a folk remedy whose roots surely must rest in Europe. Called vampirism by outsiders (a term that may never have been used by those who engaged in this practice), this remedy required exhuming the bodies of deceased relatives and checking them for unnatural signs, such as fresh blood in the heart. The implicit belief was that one of the relatives was not completely dead and was maintaining some semblance of a life by draining the vital force from living relatives.

Vampire hunters of centuries past visited morgues and cemeteries in search of the undead. The morgues I search are old newspaper archives and long-forgotten local histories, where the stories of vampires whose bodies were exhumed and examined He waiting to be rediscovered. My task is to find them and bring them back to life. Since the first publication of Food for the Dead in 2001, the Internet has grown into a web of communication whose pervasive scope was unimaginable a mere decade ago. Access to the enormous amount of data now available online has allowed my research to expand more widely, deeply, and quickly than was possible when I was writing the first edition. My vampire trail has grown to include more than thirty new American exhumations, vampire incidents that I was not aware of in 2001. This new material extends the geographic distribution of vampiric activities well beyond New England, into the upper Midwest and, perhaps, the Deep South. The time frame has expanded as well, from 1784 to, almost unbelievably, the mid-twentieth century.

Before continuing on the vampire trail, I want to address some of the questions Ive been asked about the book over the past ten years. At the top of the list:

Are (were) there really vampires?

In my prologue, when I suggest that readers should keep an open mind regarding the word vampire, I am not implying that reanimated corpses actually rise (or rose) from the dead to kill the living. I am warning readers that they are likely to encounter vampires who do not match their preconceptions. It should be clear, well before the final chapter, that I see the vampires who are the focus of this book as scapegoats. Everett Peck, who shares , addressed the question plainly and concisely. Pointing to a newspaper article about him and his story, he said, Now, what they do here, they change this around as if I believe in vampire [sic]. Now, that aint what Im sayin. Im just revealin what they believed see? Do I believe in vampire? he asked rhetorically, then answered his own question: No, I dont believe in that. Im not sure they did, but they had to come for an answer. And some of them old people probably died with that in their mind, that they did the right thing.

I use the term vampire when referring to the individuals who were exhumed, not because I believe that they were actually vampires, or even that they were labeled as vampires by their exhumers, but because it is a shorthand means for referencing them. I could have substituted a more accurate phrase, such as corpses who were suspected of being the cause, directly or indirectly, of the illness and death of their kinfolk, but that would soon become tedious to writer and reader alike, as would putting so-called in front of the term on every use. In most cases where I refer to a vampire, the context of usethe meaning of the termis apparent. Where I think there may be some ambiguity, I have tried to clarify the immediate context.

When I write in the prologue about the dual nature of being a folklorist, I am invoking not only an approach to gathering data that is employed by most folklorists, usually termed participant-observation, but also the pleasure that many of us find in our work. Play alleviates toil and tedium for every type of worker. Ive accepted that, for me, its impossible to be serious all of the timeeven if I wanted to. But it is deeper than that. We folklorists have an enduring regard for the expressive culture we interpret. Many folklorists perform what they study. At any gathering of folklorists, you will hear great fiddle playing and wonderful stories, and if you are so inclined, you can learn a variety of traditional dances. Active engagement is what has drawn some into the profession; it provides an opportunity to understand from the inside by doing. Feeling the clay imparts a quality of knowledge,

Next page