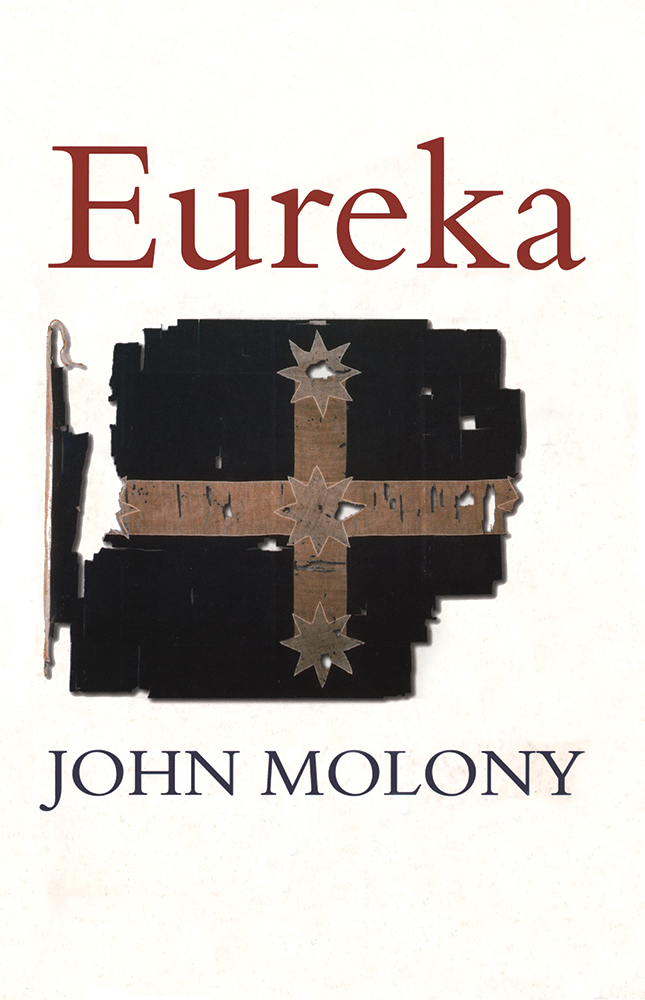

Eureka

Eureka

J ohn M olony

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

MELBOURNE UNIVERSITY PRESS

PO Box 278, Carlton South, Victoria 3053, Australia

mup-info@unimelb.edu.au

www.mup.com.au

First published 1984, by Viking

Penguin edition 1989

This edition, Melbourne University Press 2001

Text John Molony 1984, 2001

Design and typography Melbourne University Press 2001

This book is copyright. Apart from any use permitted under the Copyright Act 1968 and subsequent amendments, no part may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means or process whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher.

Designed and typeset in 11.5 point Bembo by Designpoint

Printed in Australia by Brown Prior Anderson

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Molony, John N. (John Neylon), 1927- .

Eureka.

2nd ed.

Bibliography.

Includes index.

ISBN 0 522 84962 8.

1. Eureka Stockade (Ballarat, Vic).

2. Gold minerVictoriaBallaratHistory.

3. RiotsVictoriaBallaratHistory.

4. RevolutionsVictoriaBallaratHistory.

5. Ballarat (Vic.)History. I. Title.

994.57031

Publication of this work was made possible by generous funding from the city of Ballarat.

For Dinny,

daughter of that fair city

Contents

Illustrations

between 142 and 143

Old Ballarat... in 1853-54, by Eugene von Guerard

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Eureka Riot , by Charles A. Doudiet

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Great Meeting of Gold Diggers , by Thomas Ham Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

The Government Camp, Ballarat 1854 , after Samuel Douglas Smith

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Public notices, Ballarat Public

Record Office Victoria

Plan of Attack of the Eureka Stockade , after Samuel Douglas Smith

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Eureka Stockade , by Samuel Douglas Smith

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Site of the Eureka Stockade Shortly After the Fight , by S. T. Gill

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

The Eureka flag

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Site of Bentleys Hotel, by S. T. Gill

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

The Eureka Stockade , by Beryl Ireland

La Trobe Picture Collection, State Library of Victoria

The Eureka treason trial map

Public Record Office Victoria

The Eureka Stockade Monument , by F. Niven

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Swearing Allegiance to the Southern Cross , by Charles A. Doudiet

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Eureka Slaughter , by Charles A. Doudiet

Ballarat Fine Art Gallery

Map of Ballarat, in 1854

Preface

S ometimes IT HAPPENS that the life of a book resembles that of a child as it grows to adulthood. Born in relative obscurity, the book can take on its own life and speak for itself. Once that has occurred it is good that the author, like a wise parent, step backs and grants freedom to his creation. Over time there may be some unexpected characteristics that are revealed in the book with which the author is not fully at ease. The better thing is to let them be and, even when others criticize them, remain silent. The book has taken on its own identity. To add to or delete parts from it is to change its nature.

Eureka was written with deliberate purpose. No reader could escape the fact that, constantly throughout its pages, a case was pleaded. The reason for such directness stems from my schooldays in Ballarat. The things that happened on the Eureka goldfield in 1854 made me realize that the authority of the state had had its way, and that those who acted in its name had given their side of the story. They had told their tale in the blood of some of their servants and in that of many of the diggers. It was the turn of the diggers to have their say. Eureka with its Stockade was the place of the diggers, the place where they staked their claim to be themselves, with their own values and their own convictions. My Eureka had to explain why they went to their place, why they died there, and why their memory lived on.

When it came time to recount the arrival of the 12th Regiment at Ballarat on 28 November 1854, just five days before the destruction of the Stockade and the murder of many of its guardians, it seemed that here was a chance to redress the balance. During the preceding four years the diggers had suffered injustice, indignities, violence and intolerance that I had recounted in detail. At last, according to the record and the legend, they had paid back their tormentors and they had done so with the death of one whose very profession, and seeming youth, proclaimed his innocence. Repeatedly it had been said that, in the ensuing skirmish, the regiments drummer boy, John Egan, had been mortally wounded and died soon afterwards. Throughout the decades since 1854 those who judged Eureka as a sordid, inconsequential and best-forgotten episode in colonial history continued to recall the death of Egan. They eventually erected a monument in Ballarat to his memory. Despite my unease at the flimsy nature of the evidence, the lack of a death certificate or a grave, and the inability of the regimental archivist to furnish me with details on Egan, the widespread belief in his death had become so strong that it had to be part of my narrative. It seemed almost a relief to give an account of the death because in it, surely, lay some explanation for the infamous and barbarous conduct of the military and police a few days later.

In the ensuing seventeen years much evidence has come to light about Egan and his true fate. We can now be certain that, whatever the nature of his wound, he quickly recovered and was mentioned in an official promulgation in February 1855. In 1861 John Egan was still a member of his regiment. The monument to his memory as one who died at Eureka has recently been removed from the soldiers section of the Ballarat Old Cemetery. Thus, in my renewed version of Eureka, the word mortally has been changed to seriously. There is good in this because it ill-behoved the diggers to bring death to a drummer boy. Granted that there was evil in his wounding, how much greater evil would there have been in his death? Moreover, his life removes a powerful weapon from the hands of those who were happy to use his alleged death as proof of the infamy and brutality of the diggers.

One of the constant refrains of those who continue to nurture the same concepts of authority enjoyed by the Queens representatives in 1854 is that, in telling the story of Eureka in word or symbol, it is necessary to be fair to both sides. They seem to regard the event as a kind of cricket game played under wholesome British rules in which one side won and demanded that the other gracefully bear defeat. In its stark reality Eureka was no game, but a bloodied drama of the human spirit played out on a battlefield where not even the rules of war were observed. Thankfully, relatively few men died on that battlefield in the line of duty. For each of that few, ten others died because they stood fast to the rights and dignity possessed by every human being. Their deaths and the symbol under which they died, the Southern Cross, now belong to the consciousness of the nation. They rest in the keeping of the Australian people whose democracy began on the field called Eureka.