LANCE PARKIN is a British writer best known as the author of fiction and reference books related to Doctor Who. It was in the pages of Doctor Who Weekly that he came across Alan Moores earliest professional writing, and hes followed the comic maestros career ever since. In 2001 he wrote a pocket guide to Moores work, which has since been updated and reissued. In addition to contributing pieces to magazines such as TV Zone, SFX and Doctor Who Magazine, and a stint as a television storyliner, he is the co-author of a guide to Philip Pullmans His Dark Materials trilogy. He lives in the USA.

MAGIC WORDS

THE EXTRAORDINARY LIFE OF

ALAN MOORE

LANCE PARKIN

First published in 2013

by Aurum Press Ltd, 7477 White Lion Street, London N1 9PF

www.aurumpress.co.uk

This eBook edition first published in 2013

All rights reserved

Copyright Lance Parkin 2013

Lance Parkin has asserted his moral right to be identified as the Author of this Work in accordance with the Copyright Designs and Patents Act 1988.

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights, and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly

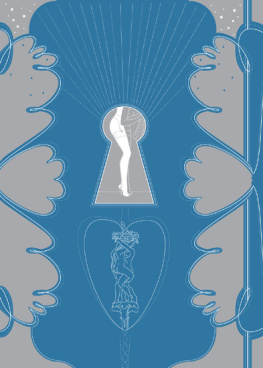

Chapter title artwork by Caio Oliveira; www.facebook.com/caioscorner

Every effort has been made to trace the copyright holders of material quoted in this book. If application is made in writing to the publisher, any omissions will be included in future editions.

eBook conversion by CPI Group

ISBN 978 1 78131 146 2

My life is peculiar. Its not the one that I was expecting. Im enjoying it. Terrific. But a bit odd.

Alan Moore, Magus Conference (2010)

W hich one is Alan Moore?

No one ever has to ask the question when Alan Moore is in the room, and it is easy to pick him out in photographs. It is apparently mandatory for anyone writing about Moore to start off by noting that he is a giant of a man (he is in fact 6ft 2in tall, but hardly grotesquely so), that he has a bushy beard and has taken to wearing chunky, segmented rings and carrying a snake-headed cane. He has been a gift to caricaturists, and works in an industry full of them. His physical appearance has frequently led people to believe he is a fearsome, peculiar person. Moore is fully aware it makes him stand out.

Alan Moores work is as distinctive as the man himself. His CV includes five-panel newspaper cartoons and a novel that is significantly longer than War and Peace; slapstick comedy and the goriest of horror; a five- or-six-page strip about Darth Vader and a three-volume slipcased work of pornography; stories about gaudy corporate-owned characters written under work-for-hire contracts; and a black-and-white self-published, creator-owned anthology magazine opposing a specific piece of Thatcher-era legislation. Moore has worked in collaborative media with over a hundred different artists, each with their own style, but when youre reading stories written by him, even those featuring iconic characters like Superman, the Joker, Jack the Ripper, Han Solo, Dorothy Gale or Jekyll and Hyde, theyre clearly all the product of the same creative mind.

The main reason people pick up his comic books is precisely because Moore wrote them. As critic Douglas Wolk notes: I still buy anything with his name on it. Even his most minor or slapdash pieces almost always inform the way I understand his major work. And the major work still sends out shockwaves, years after its been completed. Its not at all correct to say that the past twenty-five years of the history of comics are the history of Alan Moores career, but its fair to say that it sometimes seems that way. You dont have to read Sawdust Memories (1984), a three-page prose story in the pornographic magazine Knave, before you can understand the seminal graphic novel Watchmen (19867), but there are always connections and commonalities. Moore has a distinctive personal worldview and he is a constant presence in his own stories.

Much of his most prominent work was done for US publishers, has been adapted by Hollywood and is concerned with that distinctly American invention, the superhero. He grew up fascinated by superhero comics and the west coast counterculture, and hes now married to an American underground comix artist. Its forgiveable, then, that there are still people surprised to learn that Alan Moore was born, raised and has lived his entire life in Northampton, a town in the east Midlands of England. Moore has been a consistent champion of the place, once declaring, The more I looked at Northampton, the more it seemed that Northampton actually was the centre of the universe and that everything of any importance had originated from this point.

British readers will understand that this is not a widely held view of a town whose chief exports besides Moore himself are Carlsberg lager and Barclaycard bills. His American readers may not. This raises an important distinction. Moores grim and gritty reinterpretations of superheroes may weigh heavily on British perceptions of him, but they absolutely dominate his reputation in America. Many of his early series imposed realism on hokey characters like Marvelman, Swamp Thing, Batman and the Joker, reimagining their storybook worlds as unsentimental places of mid-life crisis, economic reality and brutal, often sexual, violence. Moore has been happy to play along with this image of him. When he appeared as himself on The Simpsons (in the episode Husbands and Knives, broadcast in November 2007), we learned that he was the new writer on Bart Simpsons favourite comic, Radioactive Man, and had turned him into a heroin-addicted jazz critic whos not radioactive. One of Moores characters in Supreme (19962000) was a comic book artist plagued by a British writer intent on telling a superdog rape story. Moores works for the giant American comics company DC the major entries being Swamp Thing (19847), the Superman stories For the Man Who Has Everything (1985) and Whatever Happened to the Man of Tomorrow? (1986), Watchmen, The Killing Joke (1988) and V for Vendetta (19829) are seen as classics by comics fans and are hugely influential on todays creators, all of them remaining in print and still selling strongly. However, a glance at those dates shows that it represents a mere five-year period in Moores career, thirty years ago. His work has always been broader than superhero comics for adult fanboys, and while his DC work remains important, clearly it represents a blip in his career, not the bedrock of it.

As we try to learn more about Alan Moore, it should be noted that any attempt to reconstruct his life from his stories would find little to go on. Armed with biographical information, if we delve long enough, we can unearth the odd plum: Quinchs first name is Ernest, the same as Moores father; Raoul Bojeffries is big and hairy and works in a skinning yard, as Moore did after he was expelled from Northampton School for Boys; the concentration camp in

Next page