MARY MOORE

Though my father wrote in The Listener that it is a mistake for a sculptor or painter to speak or write very often about his job. It releases tension needed for his work, as Alan Wilkinsons edited collection of HM writing and conversations points out, contradictorily the Henry Moore bibliography lists 598 entries including books, letters, exhibition catalogues, newspaper articles, periodical articles, interviews, sound recordings, films, and videos.

Certainly, from a very early age I was keenly aware that communication was a vitally important part of my fathers life, and therefore everyday family life. He took the most enormous time and care over writing anything, be it an article or just a letter. He even loved to scan the spelling and punctuation in my primary school essays. And we often played word games at lunch with the OED as referee. People came to our house all the time, from TV crews to architects, writers, world famous musicians, or just art students turning up, unannounced, on a bicycle. Our house was an open house. Astonishingly, the balance between the public and the private, the internal and the external, seemed to flow naturally and dynamically.

Without question, my father was a great communicator. It is often given that, of course hed been a teacher, born into a family of teachers. But it also helped that he just loved people. He said that he could teach anyone to draw, but what he was really teaching was how to see. And how to see in a sculptural and three-dimensional way. In talking about form-blindness in TheListener in 1937, he explains the difference between two-dimensional and three-dimensional appreciation:

Many more peopleareform-blindthancolour-blind.Thechildlearningtosee,firstdistinguishesonlytwo-dimensionalshapeithastodevelop(partlybymeansoftouch)theabilitytojudgeroughlythree-dimensionaldistances.Buthavingsatisfied therequirementsofpracticalnecessity,mostpeoplegonofarther.Thoughtheymayattainconsiderableaccuracyintheperceptionofflatform,theydonotmakethefurtherintellectualandemotionaleffortneededtocomprehendforminitsfullspatialexistence.

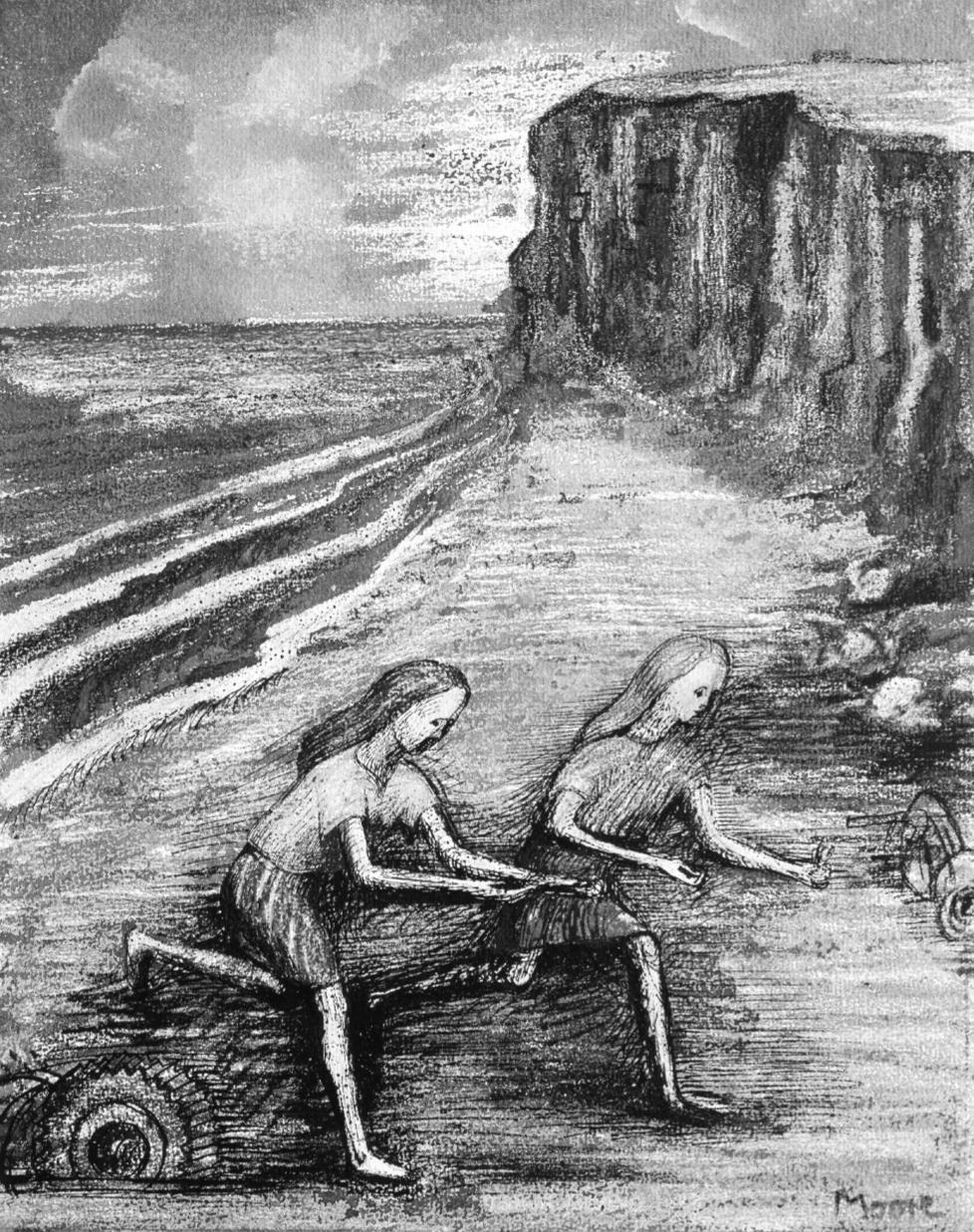

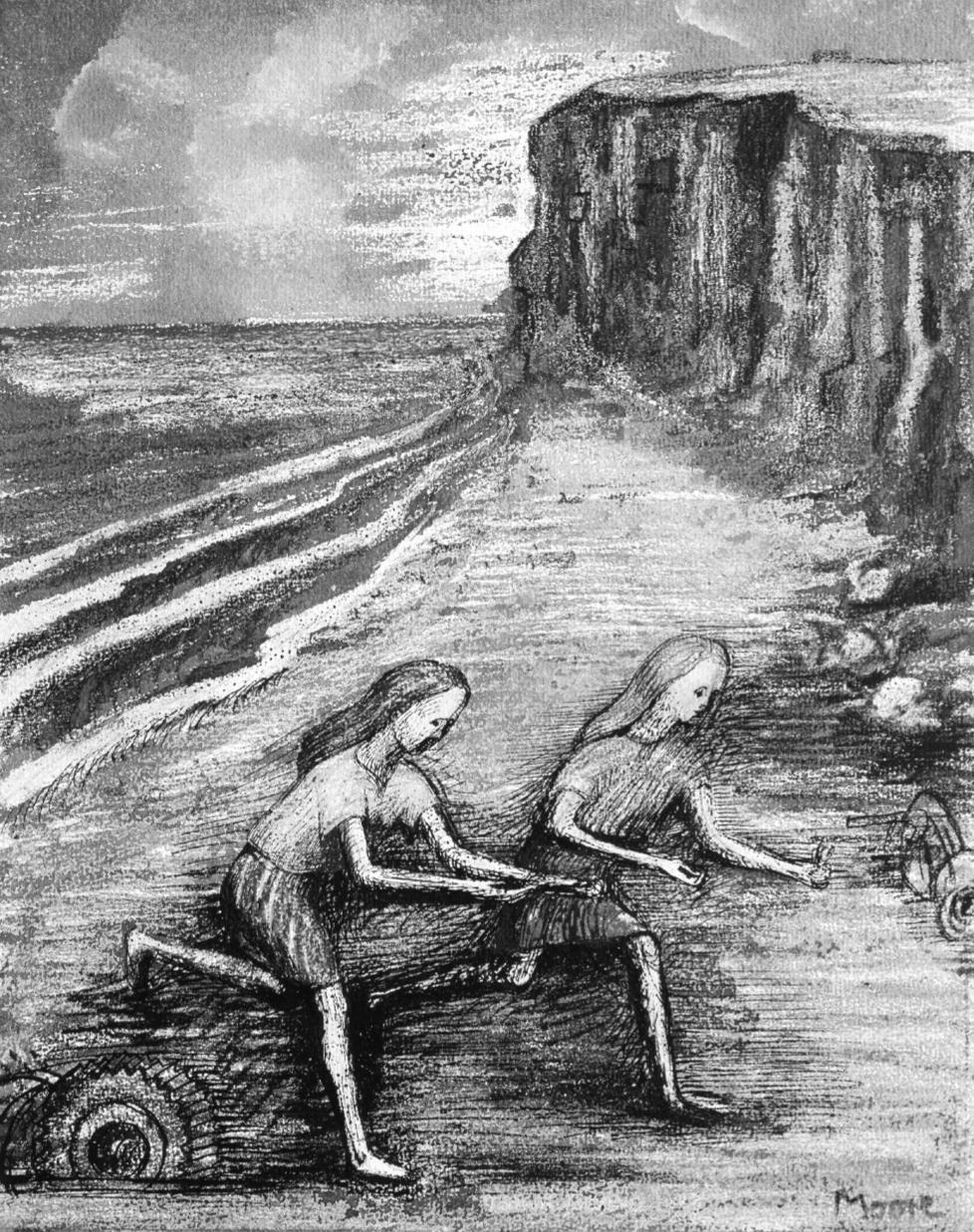

Henry Moore

IllustrationforaPoembyHerbertRead 1946

Pencil, wax crayon, charcoal, watercolour wash, pen and ink on paper

31.7 x 25.1 cm

Certainly, my childhood was a constant exposure to, the intellectual and emotional effort needed to comprehend form in its full spatial existence. It pervaded every part of daily life, in and outside the studio. In the domestic arena, most strikingly in the form of games.

These games expanded and confirmed the three-dimensional experience: eccentric games of guessing the weight of my friends at my seventh birthday party, with the help of the bathroom scales; finding the centre of a piece of paper, drawing games with eyes tight shut (teaching me to internalise and draw from visual memory); having to visualise the back of something while you looked at the front.

We used to go to Broadstairs in Kent every summer, and stayed in a boarding house on the seafront, for two weeks. I suppose these holidays were a continuation of the way my parents had spent summers all their lives, but my father could only bear to take two weeks of holiday, as he couldnt tolerate being out of the studio for any longer. On these holidays, on rainy afternoons, and indeed frequently throughout the year, wed play these familiar drawing games. The rock-pools on the beach were a source of discovery and wed come back on the Tilbury Ferry with the car boot loaded with pebbles.

From a very early age I was aware of the importance of visual images. My father constantly photographed his own work. I also realised later, just how accessible this visual information was to me in the 1960s, compared with its availability to my father in his youth. In A View of Sculpture he remarks on this development of modern communication and what an enormous impact it has had on the world view of sculpture. I was aware of how my father garnered images, for example his postcard collection. He bought postcards from every museum he visited and kept those sent by friends. His book collection and his visits to Zwemmers bookshop, where, because he could not afford to buy, he almost memorised the contents of the books, and his sketchbooks filled with drawings, done in the British Museum or Muse de Lhomme these images were notes for an internalised vocabulary of form.

His collection of natural objects and pebbles too, had much the same function as his collection of books, postcards and sketchbooks. The idea that he took inspiration from these pebbles is misleading, rather they confirmed his own inner vocabulary (see The Sculptor Speaks):

Sometimes for several years running I have been to the same part of the sea-shore but each year a new shape of pebble has caught my eye, which the year before, though it was there in hundreds, I never saw. Out of the millions of pebbles passed in walking along the shore, I choose out to see with excitement only those, which fit in with my existing form-interest at the time.

Sculptors make perfect fathers, particularly for daughters. They are physically able, immensely practical and inventive, and they can move huge chunks of stone. Above all they are emotionally intelligent and alert to their interior selves.

My father had a deep intuitive sense of how to access his subconscious and express it without allowing it to be distorted in the expression. The vocabulary he created allowed him to do that. His collection of, and internalising of, this visual imagery allowed him to create an everymans vocabulary to express the subconscious. He often referred to this in his writing. I am very much aware that associational, psychological factors play a large part in sculpture. The meaning and significance of form itself probably depends on the countless associations of mans history. He never was overt in conversation, or didactic about this. Daily life was a constant journey to enlarge and discover ways of using and expressing this vocabulary.

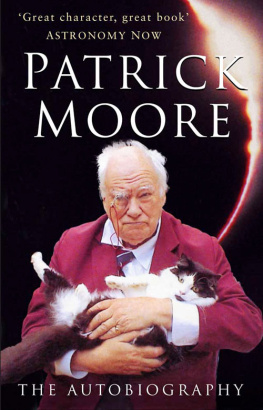

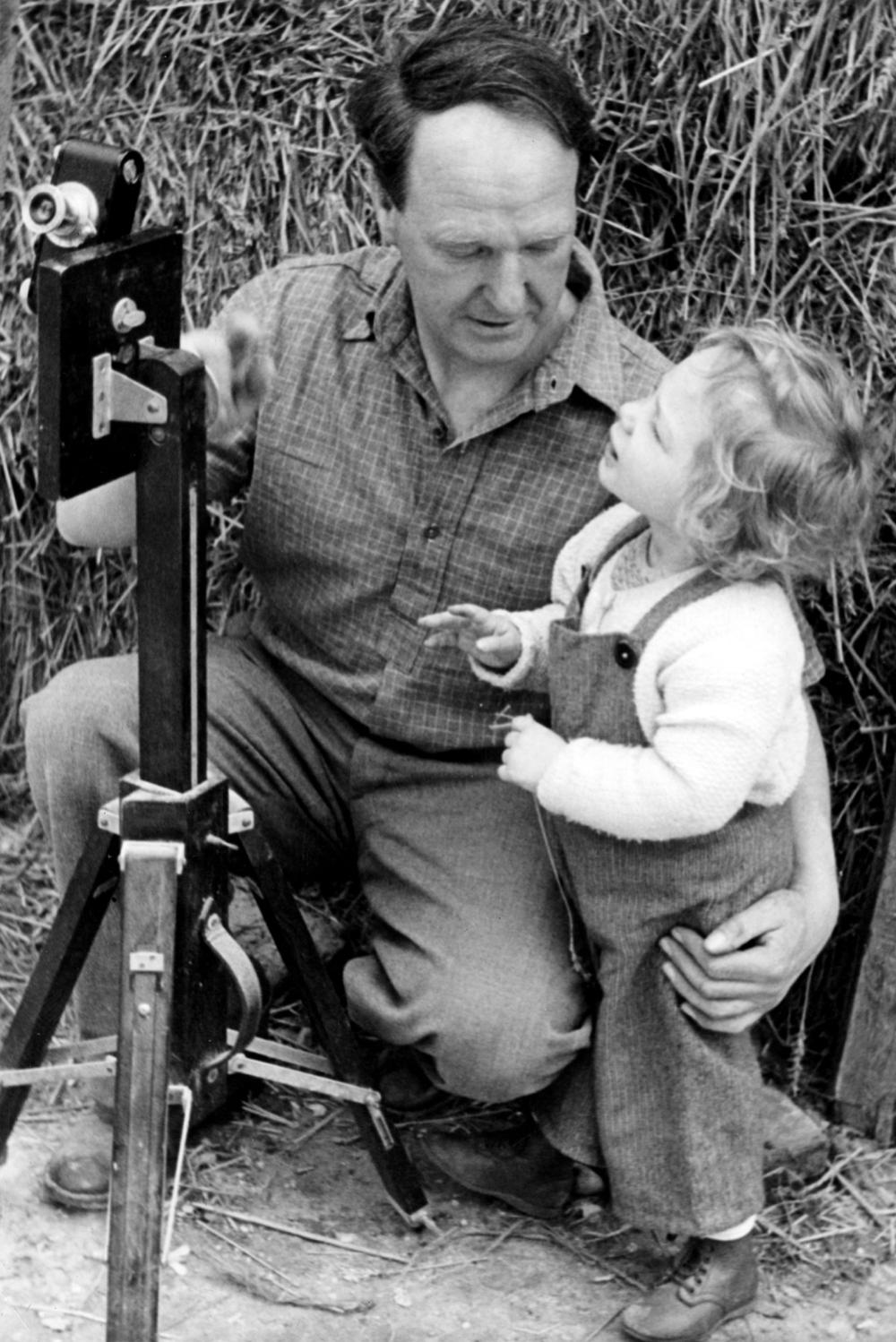

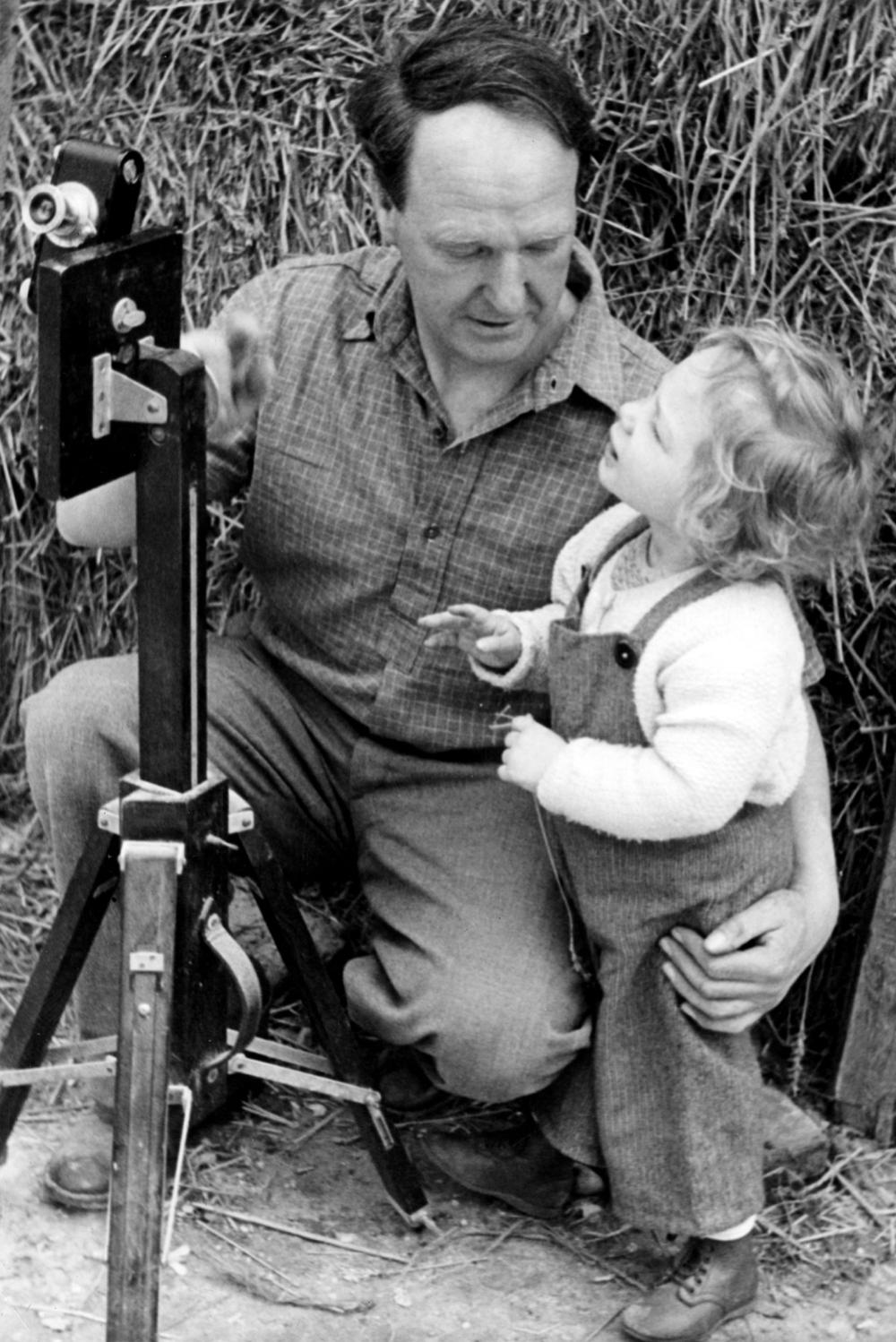

Henry Moore with his daughter Mary at Perry Green c.1948

The floor of Moores studio with a variety of boxes containing found objects. In the background is PlasterforWallRelief:MaquetteNo.5 1955

In sculpture, the later Greeks worshipped their own likenesses, making realistic representation of much greater importance than it had been at any previous period. The Renaissance revived the Greek Ideal and European sculpture since then, until recent times, has been dominated by the Greek Ideal.

The world has been producing sculpture for at least some thirty thousand years. Through modern development of communication much of this we now know and the few sculptors of a hundred years or so of Greece no longer blot our eyes to the sculptural achievements of the rest of mankind. Palaeolithic and Neolithic sculpture, Sumerian, Babylonian and Egyptian, Early Greek, Chinese, Etruscan, Indian, Mayan, Mexican and Peruvian, Romanesque, Byzantine and Gothic, Negro, South Sea Island and North American Indian sculpture; actual examples or photographs of all are available, giving us a world view of sculpture never previously possible.