Armchair Nation

ALSO BY JOE MORAN

On Roads

Queuing for Beginners

Armchair Nation

An Intimate History of Britain in Front of the TV

Joe Moran

First published in Great Britain in 2013 by

PROFILE BOOKS LTD

3A Exmouth House

Pine Street

Exmouth Market

London EC1R 0JH

www.profilebooks.com

Copyright Joe Moran 2013

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Typeset in Sabon by MacGuru Ltd

info@macguru.org.uk

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved. Without limiting the rights under copyright reserved above, no

part of this publication may be reproduced, stored or introduced into a retrieval

system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means (electronic, mechanical,

photocopying, recording or otherwise), without the prior written permission of

both the copyright owner and the publisher of this book.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available

from the British Library.

ISBN 978 1 84668 391 6

eISBN 978 1 84765 444 1

In memory of my grandmother,

Bridget Moran (19152010),

who lived half her life without television

CONTENTS

SWITCHING ON

The worst fate that can befall me is to be stranded in a town without a television set.

Matt Monro

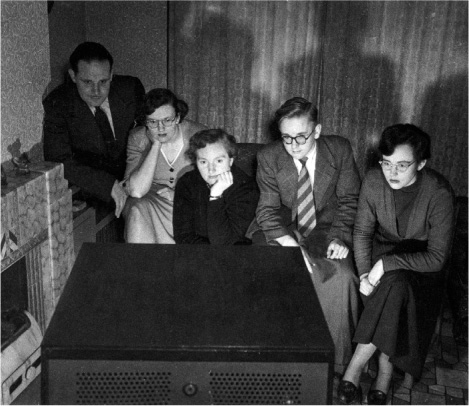

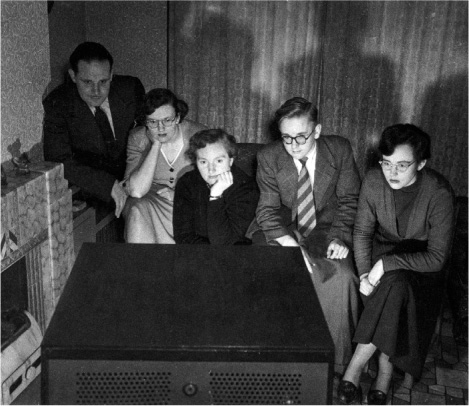

In Scandinavia they call it the war of the ants. We had a black-and-white television set with a tuning dial like a radio, and every time you switched channels you encountered this snowstorm of static, which, if you squinted a bit, resembled black ants scurrying round a white floor. Since we also had an indoor aerial and lived in a valley in the foothills of the Pennines, the television, even when it was meant to be tuned into a channel, could still blight a favourite programme with these random bursts of electromagnetic noise. Switching on the television was not an action to be taken lightly, like flicking a light switch or turning on a tap. There was something fragile and precarious about the way the radio waves had to be picked out of the air, converted into electrons and fired across the cathode ray tube towards the phosphorescent screen to make, if you were lucky, a moving picture, and if you werent, this atmospheric fuzz.

Television in our house was rationed, to half an hour a day. This law was policed inadequately, especially by our merciful mother, but its gesture to austerity was probably a blessing, for without it I would have watched television all the time. I was nearly two when, in January 1972, the telecommunications minister Christopher Chataway brought an end to the last vestige of postwar rationing. The three channels, BBC1, BBC2 and ITV, would no longer be limited to 3,330 hours each per year, but could broadcast for as long as they liked. The age of plenty this decision ushered in, which coincided with the arrival of colour TV in most homes (but not ours), is now recalled as a lost age of one-nation television in which the same programmes were watched and loved by huge and diverse audiences, a diasporic national community loosely assembled in 19 million living rooms.

Children were the most voracious viewers. As a child growing up in the early 1970s, the author D. J. Taylor has written, I watched television in the way that a whale engulfs plankton: gladly, hectically and indiscriminately. The audiences for after-school television were huge (although also fickle, halving when the clocks went forward in the spring as children abandoned it for outdoors). Eighty per cent of British children watched Scooby Doo, a cartoon series in which a gang of teenagers and a cowardly Great Dane drove round in a van solving mysteries, invariably involving petty criminals disguised as ghosts. With this possible exception, childrens TV radiated that well-meaning ethos of healthful activity and curiosity about the world that also informed organisations like the Puffin Club for young readers and Big Chief I-Spys tribe of spotters. What would make me happiest, said Monica Sims, head of childrens programmes at the BBC about her viewers, would be if they went away.

This ethos inspired programmes like Why Dont You Switch Off the Television Set and Go and Do Something Less Boring Instead?, which showed children how to make computers from index cards and knitting needles, or build their own hovercraft; Vision On, an inventively visual show for deaf children, which received about 8,000 artworks each week from mostly non-deaf children hoping to be displayed in its gallery; and the collective rituals of the BBCs flagship childrens programme, Blue Peter, whose pioneering correspondence unit invited viewers to write in with good programme ideas, the reward for which was a coveted shield badge. The letters suggested a keen sense of ownership over the programme. Dear Peter, wrote nine-year-old Ronald These participatory rituals tutorials on how to create forts from lollipop sticks or dachshund draught excluders from ladies tights and old socks, and charitable appeals for silver paper or milk bottle tops which mysteriously converted into inshore lifeboats or guide dogs for the blind seemed to be saying implicitly to us that we were not just a statistical aggregate of lots of individual viewers, but a virtual community, an extended family brought together twice weekly in front of the set.

Much of the television meant for adults also seemed to share this incantatory quality, this rhetorical conjuring up of collective life. The teatime magazine programme Nationwide, a Blue Peter for grown-ups which called itself Britains nightly mirror to the face of Britain, corralled the nation into imagined togetherness by segueing from discussions of the IMF bailout to film inserts about Herbie the skateboarding Aylesbury duck. The consumer show Thats Life was a similarly strange miscellany of high street vox pops, funny newspaper misprints and interviews with eccentrics who had invented udder warmers for cows or trained their pet dogs to say sausages. But surely the oddest collective ritual came on Saturday afternoons between the half-time football scores and the classified results on ITVs World of Sport, when Dickie Davies introduced the wrestling. Ideally, every bout should tell a little tale, wrote the wrestler Jackie Pallo in his revealingly titled memoir, You Grunt, Ill Groan. In each match, the two wrestlers would suffer their share of being held in a headlock that had them slapping the canvas in mock agony, before the baddie, usually identifiable by his leotard, lost a narrative so simple it could be understood with the sound turned down.

As I have since discovered, there were regular tabloid exposs about the wrestling, so the millions of viewers who did not know it was faked must simply not have wanted to know. The French critic Roland Barthes once observed that wrestling was not a sport at all, but a moral drama in which the audience looked for the pure gesture It did not matter that the result was fixed, only that good was seen to triumph.

Luke Hainess 2011 album, Nine and a Half Psychedelic Meditations on British Wrestling of the 1970s and Early 80s, made while his father was ill as a way of remembering watching World of Sport with him, captures perfectly this sense of the wrestling as its own weird, beguiling and wholly unironic world. Haines recorded the album in his living room with a cheap 1980s keyboard, interweaving old footage of World of Sport moments such as Kendo Nagasaki (aka Peter Thornley from Stoke) being ceremonially unmasked at Wolverhampton Civic Hall in 1977 with fantasies like the sackcloth-wearing, wild-bearded wrestler Catweazles false teeth flying out of the TV and landing at Hainess feet. The wrestling was an extreme example of what was true of most television when I was growing up: it demanded total immersion in its symbolic universe, for looking at it with an outsiders eye would break the spell and render it meaningless and ridiculous. Television performed a mostly benign confidence trick, convincing us that we believed the same things and were part of the same armchair nation.

Next page