Previous titles in the series

National Fictions

Literature, film and the construction of Australian narrative

Graeme Turner

Myths of Oz

Reading Australian Popular Culture

John Fiske Bob Hodge Graeme Turner

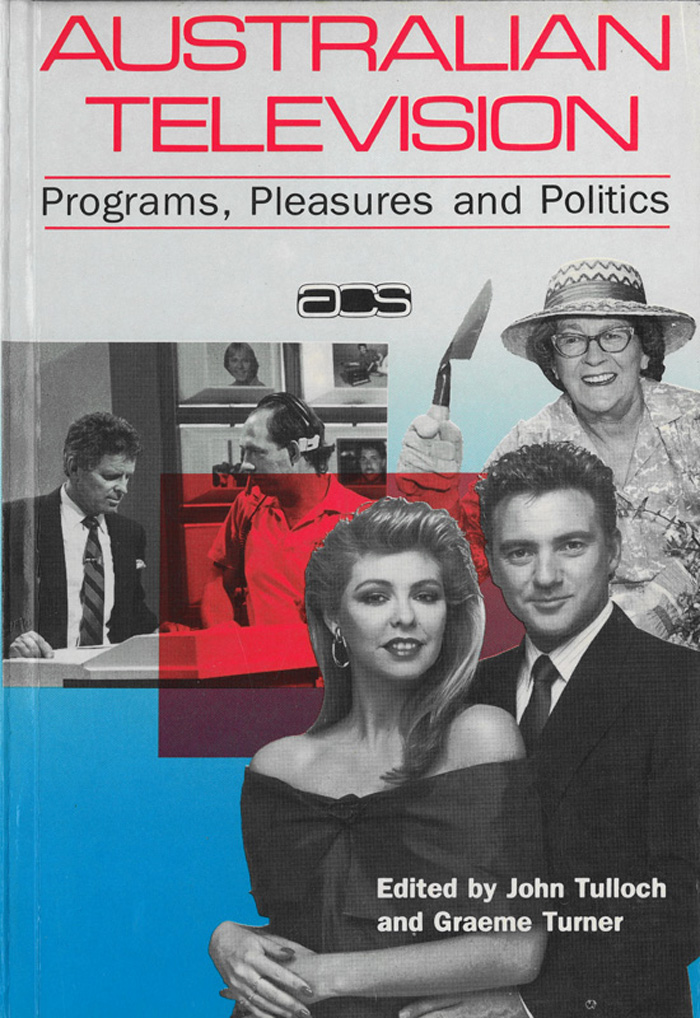

AUSTRALIAN TELEVISION

Programs, Pleasures and Politics

Edited by

John Tulloch and Graeme Turner

Australian Cultural Studies

Editor: John Tulloch

Allen & Unwin

Sydney London Boston Wellington

John Tulloch and Graeme Turner, 1989

This book is copyright under the Berne Convention.

No reproduction without permission. All rights reserved.

First published in 1989

Allen & Unwin Australia Pty Ltd

An Unwin Hyman company

8 Napier Street, North Sydney, NSW 2060 Australia

Allen & Unwin New Zealand Limited

75 Ghuznee Street, Wellington, New Zealand

Unwin Hyman Limited

1517 Broadwick Street, London W1V 1FP England

Unwin Hyman Inc.

8 Winchester Place, Winchester, Mass 01890 USA

National Library of Australia

Cataloguing-in-Publication:

Australian television: programs, pleasures & politics.

Includes index.

ISBN 0 04 380030 0.

eISBN 978 1 74269 653 9

1. Television broadcasting Social aspects Australia. 2. Television programs Australia. I. Tulloch, John, 1942 . II. Turner, Graeme. (Series: Australian cultural studies).

302.2'345'0994

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 89-83597

Contents

Albert Moran

Tom 0Regan

Graeme Turner

Stuart Cunningham

Ann Curthoys and John Docker

John Fiske

Dugald Williamson

Philip Bell and Kathe Boehringer

John Tulloch

John Hartley

Bob Hodge

Theo van Leeuwen

John Tulloch

General Editors Preface

Nowadays the social and anthropological definition of culture is probably gaining as much public currency as the aesthetic one. Particularly in Australia, politicians are liable to speak of the vital need for a domestic film industry in promoting our cultural identityand they mean by cultural identity some sense of Australianness, of our nationalism as a distinct form of social organisation. Notably, though, the emphasis tends to be on Australian film (not popular television); and not just any film, but those of quality. So the aesthetic definition tends to be smuggled back inon top of the kind of cultural nationalism which assumes that Australia is a unified entity with certain essential features that distinguish it from Britain, the USA or any other national entities which threaten us with cultural dependency.

This series is titled Australian Cultural Studies, and I should say at the outset that my understanding of Australian is not as an essentially unified category; and further, that my understanding of cultural is anthropological rather than aesthetic. By culture I mean the social production of meaning and understanding, whether in the inter-personal and practical organisation of daily routines or in broader institutional and ideological structures. I am not thinking of culture as some form of universal excellence, based on aesthetic discrimination and embodied in a pantheon of great works. Rather, I take this aesthetic definition of culture itself to be part of the social mobilisation of discourse to differentiate a cultural elite from the mass of societyas evidenced for instance in the Australian Senate Inquiry into Children and Television discussed by Bob Hodge in this book.

Unlike the cultural nationalism of our opinion leaders, Cultural Studies focusses not on the essential unity of national cultures, but on the meanings attached to social difference (as in the distinction between elite and mass taste). It analyses the construction and mobilisation of these distinctions to maintain or challenge existing power differentials, such as those of gender, class, age, race and ethnicity. In this analysis, terms designed to socially differentiate people (like lite and mass) become categories of discourse, communication and power. Hence our concern in this series is for an analytical understanding of the meanings attached to social difference within the history and politics of discourse.

It follows that the analysis of texts needs to be untied from a single-minded association with high culture (marked by authorship), but must include the popular toosince these distinctions of high and popular culture themselves need to be analysed, not assumed. Both of the books published in the series so farNational Fictions and Myths of Oz reject the assumed distinction between high and popular culture, Graeme Turner drawing on both popular film and recognised Literature for his analysis of produced texts, and John Fiske, Bob Hodge and Graeme Turner examining, on the one hand, opera house and art gallery, and on the other, pubs, beaches and shopping centres in their study of lived texts. Australian Television follows in the same tradition, examining Art and serious science documentaries on the one hand, popular quiz shows and soap opera on the other. Curthoys and Docker, for instance, speak in their chapter against high culture critics who dismiss Prisoner as an insult to the intelligencenothing but nasty people behaving nastily in a nasty situation. How different, the authors note of this high/popular culture double-standard, must Macbeth and King Lear and Hamlet benothing but nice people behaving nicely in nice situations.

Culture, as Fiske, Hodge and Turner say in Myths of Oz, grows out of the divisions of society, not its unity. It has to work to construct any unity that it has, rather than simply celebrate an achieved or natural harmony. Australian culture is then no more than the temporary, embattled construction of unity at any particular historical moment. The readings in this series of Australian Cultural Studies inevitably (and polemically) form part of the struggle to make and break the boundaries of meaning which, in conflict and collusion, dynamically define our culture.

John Tulloch

Preface

It is well over 30 years since television began transmission in Australia. In that time it has been the subject of a wide range of diverse and contradictory claims: it is both trivial and powerful; it is an important element in socialisation and a dangerous influence on children; it is passively consumed but it can teach four-year-olds to read. While there have been a number of chatty histories of Australian television, this book, despite the growth of media studies and despite the growing reputation of Australian media researchers, is the first collection of articles to deal with a wide range of Australian television through the perspectives and methodologies of television studies.

Both the editors have attempted to teach courses on television by using the only texts available: British or American readers which employ unfamiliar examples of television programs and inappropriate models of cultural relations. There has long been a need for a collection centred around the texts produced for and transmitted through Australian television. Australian Television: Programs, Pleasures and Politics, it is hoped, is the first of many such collections.

While we have tried to cover as many topics as possible this volume cannot hope to be comprehensive. The state of Australian television programming as well as of television theory is constantly changing. When this collection was first planned in 1986, it seemed unlikely that