Contents

Guide

Page List

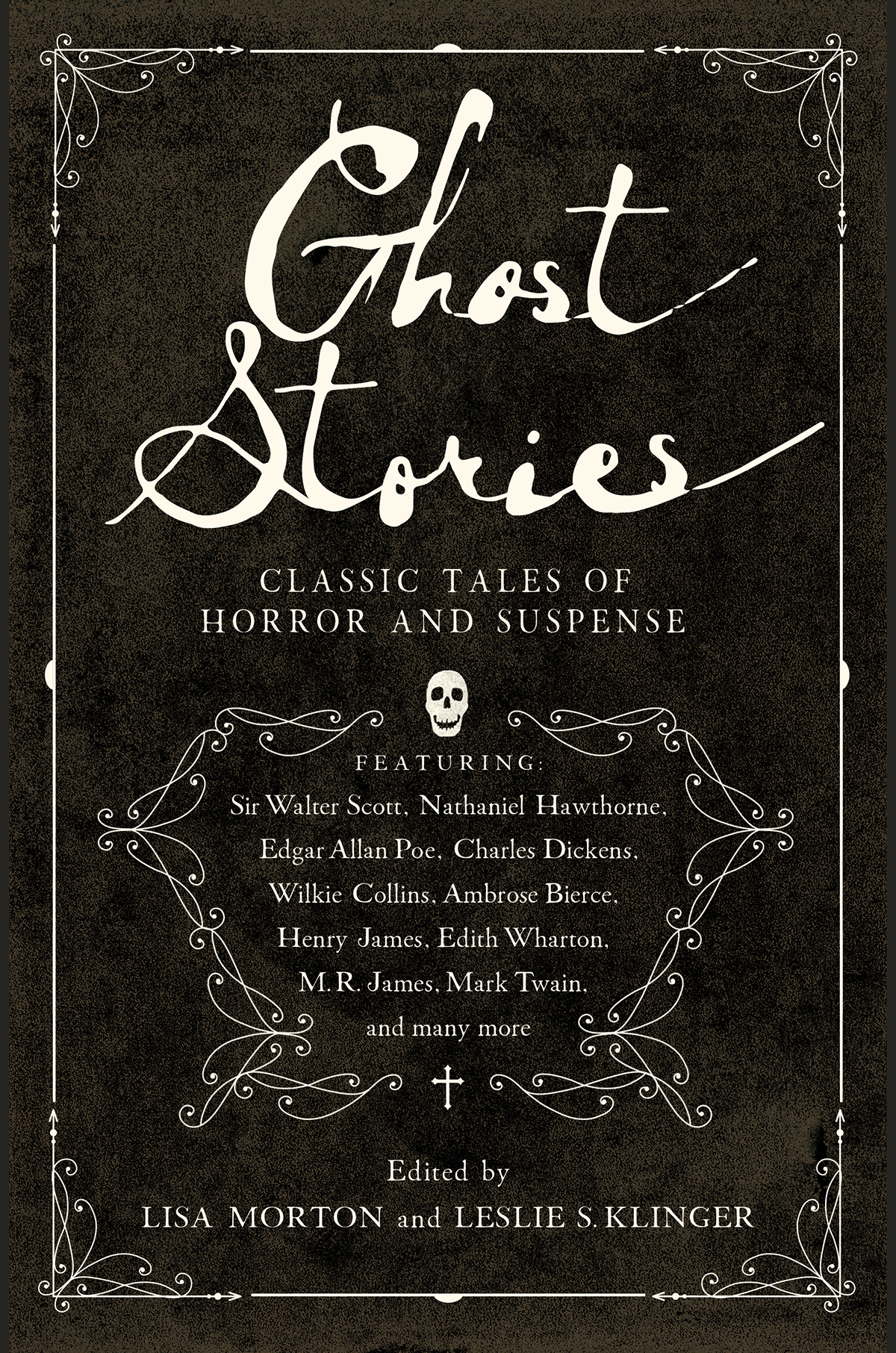

Ghost Stories

CLASSIC TALES OF HORROR AND SUSPENSE

Edited by

LISA MORTON and LESLIE S. KLINGER

For our dear departed mentor and friend Rocky Wood, whose spirit is in good company in these pages

CONTENTS

by Lisa Morton and Leslie S. Klinger

(a popular ballad)

by Johann August Apel

by Sir Walter Scott

by Nathaniel Hawthorne

by Edgar Allan Poe

by Charles Dickens

by Elizabeth Stuart Phelps

by Wilkie Collins

by Ambrose Bierce

by Charlotte (Mrs. J. H.) Riddell

by Frank Stockton

by Henry James

by Edith Wharton

by Mark Twain

by M. R. James

by Olivia Howard Dunbar

by Arthur Machen

by Georgia Wood Pangborn

by LISA MORTON and LESLIE S. KLINGER

What, after all, except for the fun of the shudder, she reflected, would he really care for any of their old ghosts?

Edith Wharton, in the short story Afterward

These things always give me an impression of truth.

M. R. James, writing about ghost stories in an 1891 letter to his parents

I n December of 1847, John D. Fox moved his family to a house in Hydesville, New York. Although the house had an odd reputation (the previous tenant had vacated because of mysterious sounds), it wasnt until March of the following year that the familys troubles began. Before long, daughters Kate and Margaret claimed to be communicating with the spirit of a peddler who had been murdered in the house. The communications took the form of rapping noises in answer to questions asked aloud.

The Fox sisters (along with a third sister, Leah, who acted as their manager) soon parlayed their rapping skills into celebrity. The young ladies held public sances, underwent tests, and inspired copycat mediums around the world. By the time the Foxes were debunked, theyd helped to inspire a new religion, Spiritualism, which was popular in both America and Great Britain, that held as its central tenet that the spirits of the dead continued to exist on another plane and could be contacted by human mediums. The Spiritualist movement had no less a figure as its international spokesperson than Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, whose wife Jean was also a medium.

Its no coincidence that the ghost story experienced a rebirth of popularity at about the same time. Both Spiritualism and the acknowledged, fictitious ghost story evolved out of the Enlightenment of the eighteenth century. Prior to that time, ghosts had either been confined to dramatic presentation (going all the way back to the haunted house comedy Mostellaria, penned by the Roman playwright Plautus several centuries before the birth of Christ) or tales that were presented as true, including mythological epics like Gilgamesh and the Iliad.

The first major work of ghostly literature is usually considered to be Horace Walpoles The Castle of Otranto. Published in 1764, Walpoles work also inaugurated the Gothic novel, a genre that waxed and waned over the next fifty years. Ghosts were a key ingredient in the great Gothics, even whenas in the works of Ann Radcliffe, the undisputed queen of the Gothicstheir manifestations were eventually revealed to be the work of deceitful mortals.

But perhaps the real precursor of the modern short ghost story was the ballad. Ballads were the preferred way of telling stories (at least in the British Isles) up until the nineteenth century, and many of them were ghost stories. Like Sweet Williams Ghost (sometimes known under the alternate title Clerk Saunders), presented below, these ballads and their numerous regional variants still retain a surprising amount of pathos, eeriness, and even a touch of gruesomeness.

As the Enlightenment brought a new belief in reason to Europe, formerly popular superstitions were reconfigured as fairy tales, intended as simple morality tales mainly for children... but not always. While the Brothers Grimm were collecting orally-transmitted folktales, eventually published in

It wasnt until 1828 that what is generally considered the first modern ghost story appeared: Sir Walter Scotts The Tapestried Chamber, included in this volume. Although Scotts tale kept certain tropes of the earlier worksthe traveler who arrives in the isolated castle, for examplehis tale is comparatively succinct and atmospheric, with chilling descriptions that would almost fit into any modern horror tale:

Upon a face which wore the fixed features of a corpse, were imprinted the traces of the vilest and most hideous passions which had animated her while she lived.

Ghosts found a willing home in the New World, too. When Nathaniel Hawthorne, one of early Americas finest writers, turned his attention to uncanny fiction, he finely portrayed a young country still trying to define itself. While his Young Goodman Brown exposed the hypocrisy of religious convictions with its tale of a journeyer who stumbles on a witches sabbat, The Gray Champion, below, became possibly the first political ghost story, offering up a patriotic defender of freedom (a theme that Arthur Machen would employ a century later in The Bowmen, also below). A few decades later, the American creator of both the modern horror storyin all its psychological and bloody gloryand the detective story, Edgar Allan Poe, would create what might be the first major story of spirit possession, with the ravishingly romantic and disturbing Ligeia, found below.

But it took the arrival of Spiritualism to really unleash the ghost story. By the 1870s, Spiritualism had millions of followers in both the United States and the British Isles, spurred on by the works of mystic philosophers like Emanuel Swedenborg, non-fiction books like Catherine Crowes 1848 The Night-side of Nature, and devastating events like the American Civil War that left parents, spouses, and siblings bereft and grieving for lost loved ones. The rise of Spiritualism in the nineteenth century is often thought of as a reaction to the scientific materialism of the Enlightenment, and indeed, even the Spiritualists at the time acknowledged this. As Crowe put it:

The contemptuous scepticism of the last age is yielding to a more humble spirit of enquiry; and there is a large class of persons amongst the most enlightened of the present, who are beginning to believe, that much which they had been taught to reject as fable, has been, in reality, ill-understood truth.

Just as wealthy Victorians on both sides of the Atlantic were flocking to sances in hopes of seeing a table levitate or hearing a dead loved one miraculously channeled by an attractive young medium, so at home they consumed ghost stories in the pages of the magazines that had become popular thanks to new printing technologies. Many of the ghost stories in this volume reflected Spiritualist beliefs; in some (Mrs. Zant and Ghost by Wilkie Collins, for example), the true horror was a mortal antagonist, while in others (Elizabeth Stuart Phelpss Since I Died, or Olivia Howard Dunbars The Shell of Sense), the human inability to grasp the cosmos was a source of terror.

Not all of the late-nineteenth-century ghost stories were influenced by Spiritualism, however. The study of folklore was in vogue, thanks to efforts like Chambers Book of Days; ghost stories were traditional Christmas entertainments (not on, as is now the case, Halloween!), and often played on folklore (Charlotte Riddells marvelously entertaining The Last of Squire Ennismore) and urban legend (Dickens No. 1 Branch Line: The Signalman), both reprinted here.