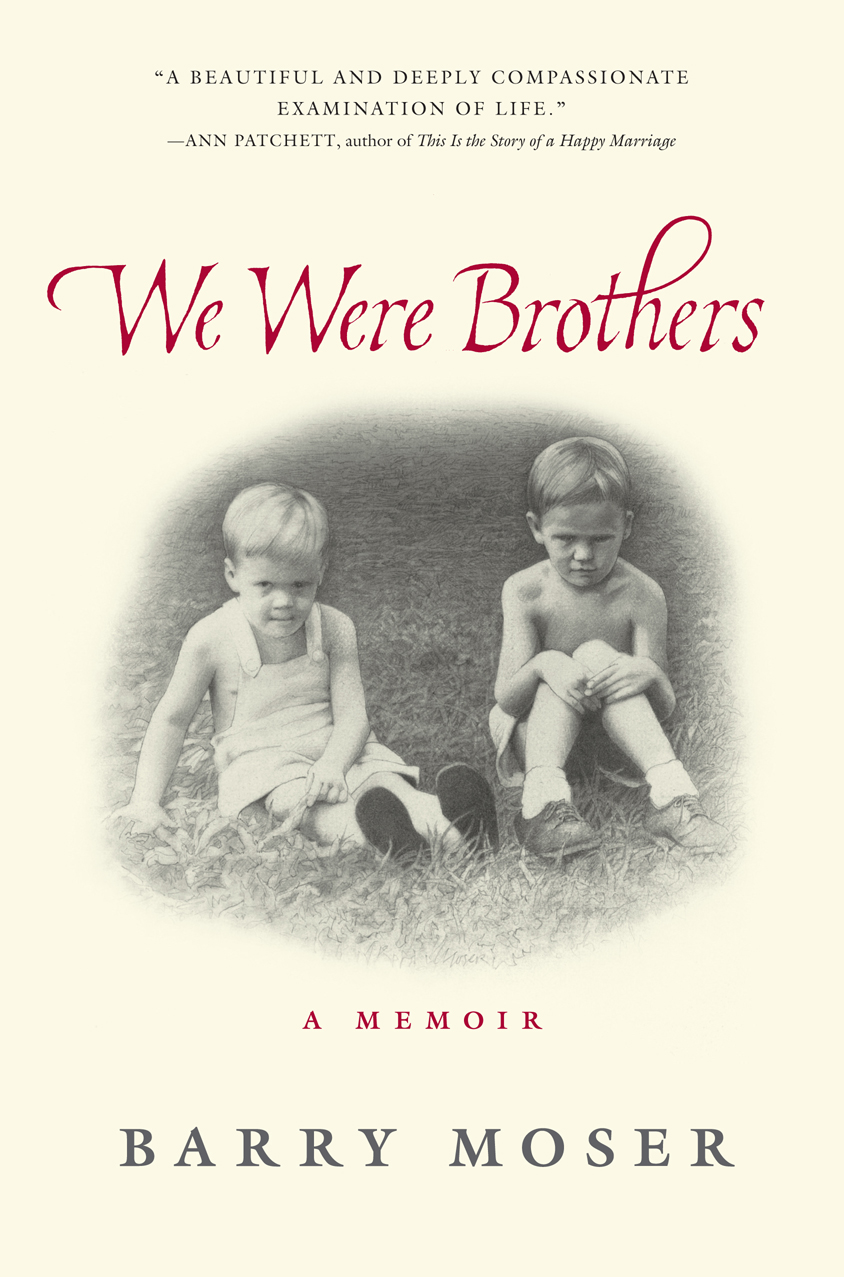

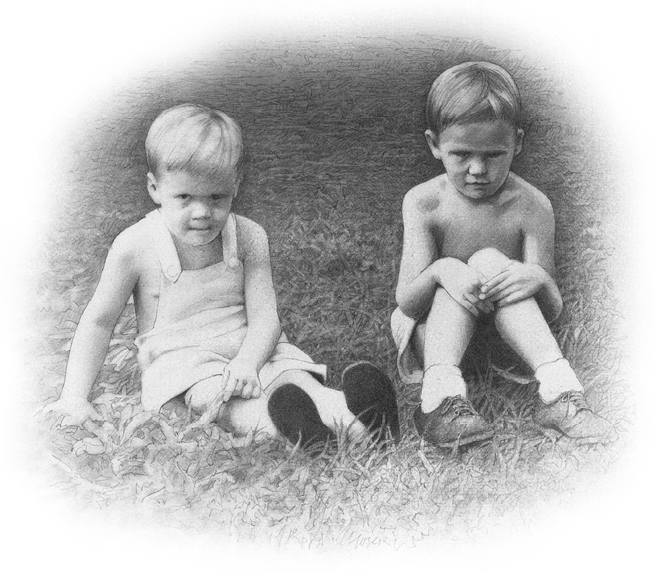

PROLOGUE

I HAVE A FAMILY photograph that was taken on a Christmas Eve sometime in the early 1960s. We are in my aunts living room. Two generations pose in front of a fireplace that, as far as I know, never entertained an actual fire. Above the garlanded mantel hangs a portrait of my aunts late husband that I painted when I was in high school. The people in the picture are my mothers people: her husband, sisters, and brother are there, as well as my brother and me. Most of us lived cheek to jowl on a short stretch of a Chattanooga country road.

All the people in the picture are dead nowMother, Daddy, aunts, uncles, cousins, and my brother, Tommy. I am the only one still alive.

Since my brother died I have reflected on our relationship, mostly in the context of that country road and those people in the pictureHaggards, Holmeses, Coxes, Moores, Mosers. And I have reflected on the culture that shaped them and shaped my brother and me. Without opportunity to be otherwise, Tommy and I were racists, born into the byzantine machinations of the Jim Crow South. Tommy in 1937. I in 1940.

As we grew up Tommy and I went our separate ways. He stayed in the South. I moved to New England. And for nearly forty years the distance between us widened and at one point it seemed that the gulf had become so vast it would never be bridged and we would be forever strangers. We both hardened, but I hardened more than he.

Though when I read novels and stories or see films in which brothers are close and go places together and have adventures, I often weep. I weep even when they fight, as they do in Jim Harrisons splendid novella Legends of the Fall, because in the end blood and love win out over the divisiveness that once separated the brothers. Or the contentious, yet deeply affectionate relationship between Norman Maclean and his estranged brother, Paul, in A River Runs Through It, or between Alvin and Lyle Straight in the The Straight Story. The childhood miseries of Frank and Malachy McCourt in Angelas Ashes moved me profoundly because they were shared miseries between the brothers.

In Abraham Vergheses transcendent Cutting for Stone, Shiva Stone, a surgeon, says that life is in the end about fixing holes. Though Shiva speaks about surgical holes, his twin brother, Marion Stone, who is also a surgeon, takes it as a metaphor for another kind of hole, and that is the hole that divides a family. What he owes his brother most is to tell the story.... Only the telling can heal the rift that separates my brother and me, he says. Yes, I have infinite faith in the craft of surgery, but no surgeon can heal the kind of wound that divides two brothers. Where silk and steel fail, story must succeed.

OUR FATHER, ARTHUR BOYD MOSER, had no siblings. However our daddy (our stepfather), Chesher Holmes, had four brothers, all younger than he and all of whom lived in Chattanooga or within easy driving distance. The few times we saw his brothers were at breakfast on Christmas Day at their mothers place on the western slope of Missionary Ridge. That was our only connection. None of his brothers ever set foot in our house on Shallowford Road. Daddy told me once that he had raised his four brothers, his daughter, and my brother and meand that may very well be the case, certainly the last part of it is. But the thing is, Daddy didnt much talk about his brothers. Oh, he told stories about his brother David, who had a goat cart as a boy, and about his brother Martin, who was an extra in a war movie that starred Victor Mature, but thats about all.

He didnt fish or hunt with his brothers, nor did he socialize with them. As a family, we visited his youngest brother, Gene, at his home when he was recuperating from a motorcycle accident in which he lost one of his legs. We visited his brother Dan and his wife, Beverly, at his mothers house after Beverly had given birth to a new baby. And I have a vague memory of visiting with his brother David after he returned from the European Theater in World War II. He gave Daddy a 9mm Mauser rifle that he brought home as a war trophy.

My brother and I were never privy to any personal interactions between the Holmes brothers other than on those Christmas mornings when they bantered among themselves while they posed for photographs with their aging mother. All of them smiling broadly, presenting the face of a congenial family. And maybe they were, who knows? But there were never any displays of affection. There was no playful roughhousing of the sort that would make affection seem to be part of the fabric of their relationship.

On the other hand my brother and I were not privy to any discord, if there was any, among the Holmes brothers. To us they were a world apart. Five entities who went about their individual lives, unconnected to and seemingly unconcerned with each other.

It was like that with my uncle Bob, too. He had two brothers, but he spent his weekends fishing with Daddy rather than hanging out with his kin. Like Daddy, he saw them on special occasions: their mothers and fathers birthdays, Christmas, New Years Day.

I know more about my grandfather, Albert Moser, and his relationship with his two brothers, Will and George, than I do of any of the other brotherhoods in my family. From a 1932 letter George Moser wrote to his nephew, my father, I know that those brothers fought, that they went to hog auctions together, that they loved dogs, that they harbored deep resentments about the outcome of the Civil War and the subsequent Reconstruction. And I know that George greatly admired his older brother, Albert.

But the only brotherhood I have any firsthand knowledge of is my own, and, for the most part, it was heavy ladened and knotty. Like all siblings, we vied for the attention of our elders. We both wanted to be the favorite son. We both wanted to have the most friends or to be one specific friends best friend. When I see the genuine and gentle interactions between my four nephews, I respond with gladnessand tears. I envy them that. Prodigously.

Though our personalities were like oil and water, I loved my brother and he loved me. It just took too long for us to understand it. To admit it. And to try to do something about it. The blame for our conflicts does not lie at my brothers feet alone because I certainly contributed to the strife that so nettled our relationship. But I am the teller of this story, or at least I am the teller of this version of this story, and I can only see it through my eyes. I can recall it only through my memories, and thus I have the advantage.

In the end, I rue the fact that during our lifetimes my brother, Thomas LaFayette Moser, and I rarely experienced deeply affectionate moments like those real and fictive that I have observed and read about. Only near the end of his lifeand after forty years of living a thousand miles apart, both geographically and emotionally, a distance that was punctuated by rare visits and infrequent phone callsdid the rancor genuinely abate. We were both in our sixties.

What follows is the story of that brotherhood. But to tell you the story of that brotherhood, I have to tell, as well as my abilities will allow, the story of our family, and of the neighborhood we lived in.