In the past it was taken for granted that when travellers said goodbye they became inaccessible for an indefinite period, only sending back the occasional message (a year or two out of date) in a cleft stick. But now we are expected to remain in touch with home, friends and problems; our escape is merely physical, the mental and emotional shackles staying firmly in place.

On and off, over the years, I have brooded on this constraint. Then suddenly I was vouchsafed a blinding glimpse of the obvious. Ease of communication could be defeated by not telling anybody not even ones nearest and dearest where one was going. If nobody knows which continent a traveller is travelling on, enjoyment of the present cannot be threatened by calamities back home, like news of your dog being run over, your house being burned to the ground or your bank going into liquidation.

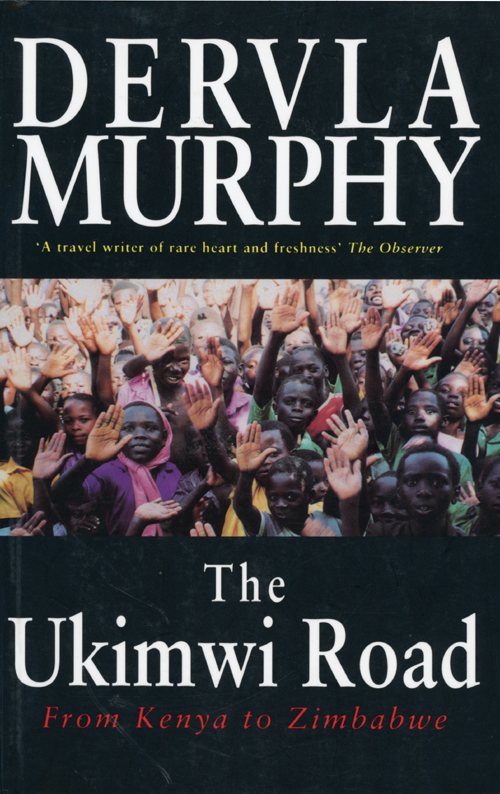

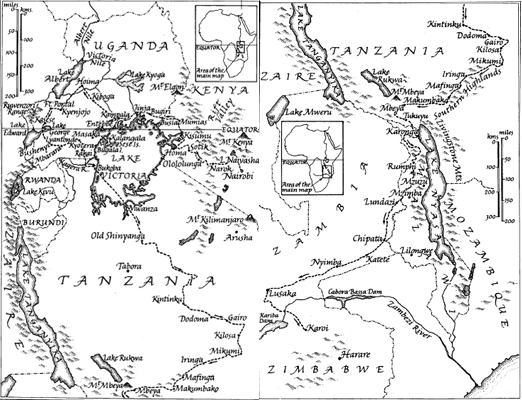

In January 1992 I craved this degree of isolation. During the previous few years a combination of circumstances (not least my involvement in Rumanias post-Ceausescu problems) had put me under some stress and my self-prescribed unwinding therapy was a cycle tour from Kenya to Zimbabwe via Uganda, Tanzania, Malawi and Zambia a carefree ramble through some of the least hot areas of sub-Saharan Africa. I therefore presented myself, for my sixtieth birthday, with a Dawes Ascent mountain-bike, the cyclists equivalent of a Rolls-Royce, named Lear. Then I bought a ticket to Nairobi and told all concerned that I was about to indulge in a four-month mystery tour.

At once all concerned rose up in arms. I was being, they alleged, perverse, selfish, irresponsible and neurotic. They needed to keep in touch, to know that I was safe. The illogic of this attitude escaped them. If I were unsafe diseased, injured, jailed, robbed, murdered their knowing about it would not materially alter my situation but would distress them. So my insistence on not keeping in touch was a kindness; every sensible person assumes no news to be good news.

I was, I suppose, trying to create an oasis in time. However, it didnt work out quite like that; if you leave your own problems behind, other peoples come along to fill the vacuum a lesson that lay in the future as my airbus took off from Heathrow on 2 March. It was three-quarters empty: worrying for Kenya Airways but agreeable for us passengers. After a tolerable dinner and several free Tusker beers I slept well, lying luxuriously along three seats.

A pair of Heathrow scaremongers had warned me that most Nairobi airport officials are surly predators. But as we landed at 7.30 a.m. I had another concern: would Lear be grievously maimed by the baggage-handlers? Most cyclists are capable of attending to their machines injuries; I am not. Anxiously I asked a tall, handsome uniformed official his precise function unclear where bicycles could be collected. He gazed down at me reflectively, then wondered, Why did you bring a bicycle? It is better for old people to travel in vehicles. Already I was streaming sweat, in no position to dispute his next comment. It is too hot to cycle. Even for us it is too hot before the rains. Why did you come with a bicycle in the hot season?

For cat-sitter reasons (my home is owned by three cats) this journey had been started a month earlier than originally planned. That a travellers timing should be determined by feline whims is plainly absurd but it seemed unnecessary to expose this deranged area of my psyche to an airport official. Meanwhile, as we chattered unproductively, someone might be bikenapping Lear

The young man nodded towards the conveyor-belt and said, All luggage comes there. Spatially a bicycle could not come there so I hurried to the Information kiosk where a small round amiable man observed, with a twinkle, that in Kenya lions eat cyclists. Then, intuiting that I was in no mood for banter, he indicated a nearby doorway.

In a grey concrete hanger I found decrepit tractors drawing trailers of luggage through greasy diesel clouds. At last one of them returned with Lear only Lear on board. When I eagerly leaped forward, the tractor-driver required no documentary proof of ownership; perhaps my joyous relief was proof enough. Beside the kiosk I set about unwrapping Lear from those many layers of plastic sheeting in which he had been dressed for his journey. Despite this precaution, two nasty gashes marked the saddle and the right-hand gear lever had been dented. Mercifully, neither injury affected his performance. A small but fascinated crowd gathered to watch me adjusting the handlebars before beginning a humiliating struggle to screw on the pedals.

![Harry Turtledove - Worlds that werent : [novellas of alternate history]](/uploads/posts/book/79050/thumbs/harry-turtledove-worlds-that-weren-t-novellas.jpg)