Contents

Guide

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

To my grandparents, Nathan and Ida

And to the workers

I dont know how it came to me, so much common sense.

Nathan Handwerker

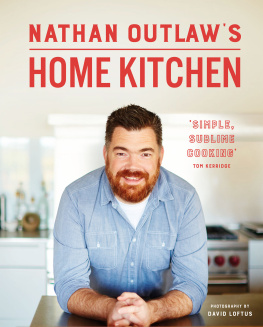

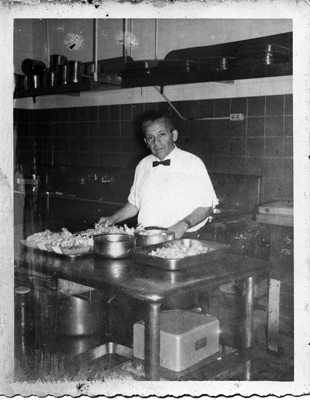

Give em and let em eat! Nathan Handwerker of Nathans Famous.

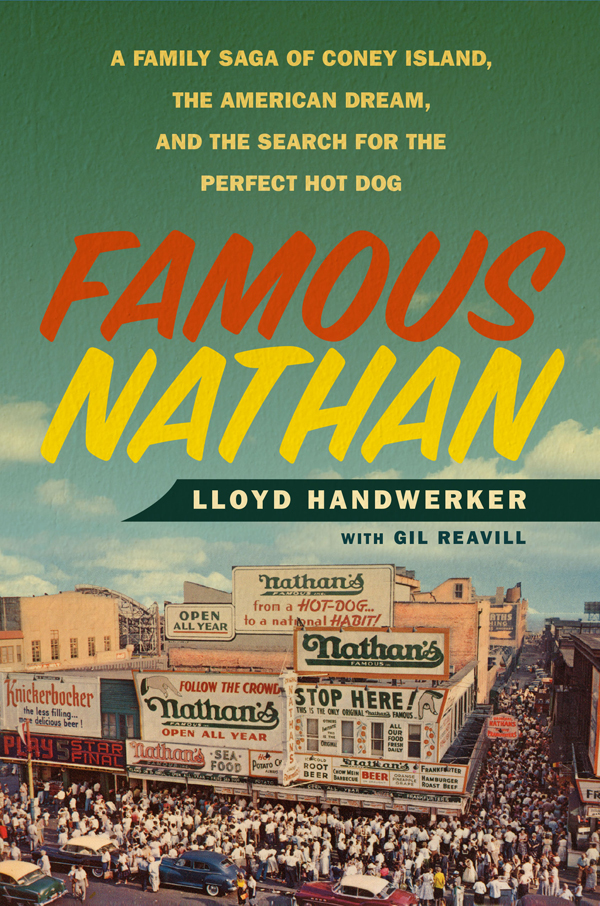

JULY 4 TH , 2015, a Saturday. The corner of Surf and Stillwell Avenues, Coney Island, Brooklyn. The world famous Nathans Famous International Hot DogEating Contest is about to begin.

The Barnum-like voice of George Shea, the events straw-hatted announcer, booms over the public address system as he paces across the stage. In the name of all that is holy, I have never seen a better crowd! Ladies and gentlemen, its the Fourth of July!

Salt air mixes with the scent of fried food. Hoarse shouts and the screams of seagulls melt into the beat from competing loudspeakers. The Bunnettes, the contests cheerfully amateur dancers, warm up the crowd with random shakes and shimmies. Near me a twenty-something kid holds up a placard that reads, Nathan Handwerker is my homeboy. I ask him if he knows who Nathan Handwerker is.

You mean hes a real person? he asks.

I wonder how many contest-goers know the story of how Nathans Famous began, who founded the place, and the family saga behind it, the Jewish immigrant who arrived almost penniless in America, only to go on to establish the iconic hot dog stand that lends its name to todays internationally celebrated event.

Are you ready? bellows Shea. Its go time! Count it down with me! Ten, nine, eight

On the stage with him are the reigning champion, Joey Chestnut, and his closest competitor, Matt Stonie. Spectators in the tens of thousands cram Coneys streets and beaches. Everyone pushes toward Nathans Famous. Audience members hoist oversize photographic cutouts of their favorite competitors. Hot dog outfits and Uncle Sam regalia are everywhere.

Every July 4, this small patch of Brooklyn becomes the center of the media universe. As it has every year since 2004, ESPN is broadcasting the contest live. The event pulls in higher ratings than the Major League Baseball games broadcast that day. The millions watching on TV dwarf the number of people in the streets. Yet it seems everyone in the world is here, jostling and pushing.

Seven, six

The event has grown enormously in the past few decades, from a folding table set up in an alleyway to this. Whatever this is.

A sporting event? It has to be, since ESPN is here. A spectacle? The incredible number of people present indicates it is so. A joke? No one seems to take the whole business quite seriously. The end of the world? So say a few old-timers and wet-blanket cultural critics.

Five, four

The crowd surges forward, eager. The eatersinsiders know to call them gurgitatorspoise over their piles of hot dogs, ready to wolf them down.

The audience members scream the countdown along with George Shea.

Three, two, onego!

Cheers erupt as the contestants begin their frantic gulping and gorging.

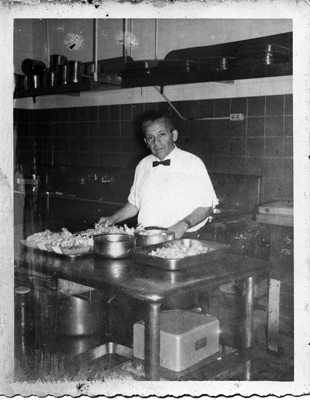

It all makes for slightly surreal entertainment. I think how fast food was pretty much invented here on the corner of Surf and Seaside Walk, with Nathan Handwerker being one of its most visible pioneers. On a summer weekend, in an era when McDonalds wasnt even a gleam in Ray Krocs eye, Nathans restaurant sold as many as seventy-five thousand hot dogs. The owner urged on his employees with a constant refrain: Give em and let em eat!

Sammy Fariello, the longtime star counterman at Nathans Famous, could serve sixty frankfurters in toasted buns in sixty seconds. In 1981, on the occasion of the sixty-fifth anniversary of its founding, Nathans Famous celebrated the sale (to a Brooklyn cop) of its 565 millionth hot dog.

It wasnt called fast food back when Nathan started his Coney Island restaurant in 1916. The phrase wouldnt become popular until the 1950s. In Brooklyn slang, Nathans Famous was termed a grab joint, where you could get fed quickly and cheaply. The speed of service is echoed, or perhaps parodied, in the international hot dogeating contest.

With the crowd packing in tighter by the minute, I can barely glimpse the stage. The Bunnettes hold up scorecards behind each competitor, like ring girls at a big fight. Three minutes into the ten-minute contest, the two leading eaters are neck and neck, having each just swallowed their nineteenth dog.

* * *

Nathan Handwerker was my grandfather. He founded Nathans Famous in 1916. With his wife, my grandmother Ida, he worked hard to build it into one of the most popular restaurants in the world. During the heyday of the early 1950s, the business grossed $3 million annually. In the sixties, Jackie Kennedy ate in the restaurants tiny dining room. Both Barbra Streisand and Frank Sinatra ordered Nathans Famous frankfurters flown over when they were performing in London. But the place was never about celebrities. It was democratic through and through.

When I was a child, I would visit my grandfather at the original Coney Island restaurant. I remember following him through the busy back kitchens, feeling self-conscious that the workers were pointing me out as the grandson of the founder. Back then, I had only a general idea that the place was cherished by a lot of New Yorkers and visited by people from all over America and the world.

As I got older, I became more curious. I was eager to know the full story of Nathan and Ida. I also wanted to explore the lives of my father and uncle, Sol and Murray Handwerker, who had worked with Nathan but experienced a bitter sibling rivalry and eventually had a falling out.

Beyond my grandfathers rags-to-riches story, and behind the family disagreements, I knew there was something else worth exploring, something harder to pin down. A mythology surrounded Nathans Famous. Whenever I would mention the place, people would speak of it with reverence. It seemed to connect them to their childhoods, to summer days on the beach, to a time long past but caught in memory.

We used to

I went with my parents

Every summer weekend, wed visit

So the stories always started, and theyd spill out with wistful enthusiasm.

I loved those crinkle-cut potatoes

I can still taste

It became clear to me early on that the story of my family involved something great, a tale of America itself. I studied photography and filmmaking in school, and began speaking with dozens of family members, former employees, patrons, friends, and business associates of my grandparents. I logged over three hundred hours of interviews. I then wove it all together in a documentary and now this book, all in an effort to paint a portrait of my grandfathers legacy.

The complete story has never really been told. A collection of widely circulated legends has developed around Nathans Famous, most of them the work of various public relations executives as Nathans business grew and grew. The nostalgia with which people approach Coney Island, their childhoods, the taste of Nathans hot dogs, make them wish all the tall tales were true.