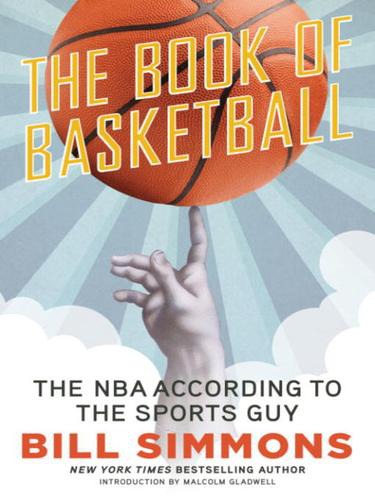

ALSO BY BILL SIMMONS

Now I Can Die in Peace:

How the Sports Guy Found Salvation Thanks

to the World Champion (Twice!) Red Sox

For my father and for my son.

I hope I can be half as good of a dad.

FOREWORD

Malcolm Gladwell

1.

Not long ago, Bill Simmons decided to lobby for the job of general manager of the Minnesota Timberwolves. If you are a regular reader of Bills, you will know this, because he would make references to his campaign from time to time in his column. But if you are a regular reader of Bills column, you also know enough to be a little unsure about what to make of his putative candidacy. Bill, after all, has a very active sense of humor. He likes messing with people, the way he used to mess with Isiah Thomas, back when Thomas was suffering from a rare psychiatric disorder that made him confuse Eddy Curry with Bill Russell. Even after I learned that the Minnesota front office had received something like twelve thousand emails from fans arguing for the Sports Guy, my position was that this was a very elaborate joke. Look, I know Bill. He lives in Los Angeles. When he landed there from Boston, he got down on his hands and knees and kissed the tarmac. Hes not leaving the sunshine for the Minnesota winter. Plus, Bill is a journalist, right? Hes a fan. He only knows what you know from watching games on TV. But then I read this quite remarkable book that you have in your hands, and I realized how utterly wrong I was. Simmons knows basketball. Hes serious. And the T-wolves should be, too.

2.

What is Bill Simmons like? This is not an irrelevant question, because it explains a lot about why The Book of Basketball is the way it is. The short answer is that Bill is exactly like you or me. Hes a fanan obsessive fan, in the best sense of the word. I have a friend whose son grew up with the Yankees in their heyday and just assumed that every fall would bring another World Series ring. But then Rivera blew that save, and the kid was devastated. He cried. He didnt talk for days. The world as he knew it had collapsed. Now thats a fan, and thats what Simmons is.

The difference, of course, is that ordinary fans like you or me have limits to our obsession. We have jobs. We have girlfriends and wives. Whenever I ask my friend Bruce to come to my house to watch football, he always says he has to ask his girlfriend if he has any cap room. I suspect all adults have some version of that constraint. Bill does not. Why? Because watching sports is his job. Pause for a moment and wrap your mind around the genius of his position. Honey, I have to work late tonight means that the Lakers game went into triple overtime. I cant tonight. Work is stressing me out means that the Patriots lost on a last-minute field goal. This is a man with five flat-screen TVs in his office. It is hard to know which part of that fact is more awe-inspiring: that he can watch five games simultaneously or that he gets to call the room where he can watch five games simultaneously his office.

The other part about being a fan is that a fan is always an outsider. Most sportswriters are not, by this definition, fans. They capitalize on their access to athletes. They spoke to Kobe last night, and Kobe says his finger is going to be fine. They spent three days fly-fishing with Brett Favre in March, and Brett says hes definitely coming back for another season. There is nothing wrong, in and of itself, with that kind of approach to sports. But it has its limits. The insider, inevitably, starts to play favorites. He shades his criticisms, just a little, because if he doesnt, well, what if Kobe wont take his calls anymore? This book is not the work of an insider. Its the work of someone with five TVs in his office who has a reasoned opinion on Game 5 of the 1986 Eastern Conference semifinals because he watched Game 5 of the 1986 Eastern Conference semifinals in 1986, and thenjust to make sure his memory wasnt playing tricks on himgot the tape and rewatched it three times on some random Tuesday morning last spring. You and I cannot do that because we have no cap room. Thats why we have Simmons.

3.

You will have noticed, by now, that The Book of Basketball is very large. I can safely say that it is the longest book that I have read since I was in college. Please do not be put off by this fact. If this were a novel, you would be under some obligation to read it all at once or otherwise youd lose track of the plot. (Wait. Was Celeste married to Ambrose, or were they the ones who had the affair at the Holiday Inn?) But it isnt a novel. It is, rather, a series of loosely connected arguments and riffs and lists and stories that you can pick up and put down at any time. This is the basketball version of the old Baseball Abstracts that Bill James used to put out in the 1980s. Its long because it needs to be longbecause the goal of this book is to help us understand the connection between things like, say, Elgin Baylor and Michael Jordan, and to do that you have to understand exactly who Baylor was. And because Bill didnt want to just rank the top ten players of all time, or the top twenty-five, since those are the ones that we know about. He wanted to rank the top ninety-six, and then also mention the ones who almost made the cut, and he wanted to make the case for every one of his positionswith wit and evidence and reason. And as you read it youll realize not only that you now understand basketball in a way that you never have before but also that theres never been a book about basketball quite like this. So take your time. Set aside a few weeks. You wont lose track of the characters. You know the characters. What you may not know is just how good Bernard King was, or why Pippen belongs on the all-time team. (By the way, make sure to read the footnotes. God knows why, but Simmons is the master of the footnote.)

One last point. This book is supposed to start arguments. Im still flabbergasted at how high he ranks Allen Iverson, for example, or why Kevin Johnson barely cracks the pyramid. I seem to remember that in his day K.J. was unstoppable. But then again, Im relying on my memory. Simmons went back and looked at the tape some random Tuesday afternoon when the rest of us were at work. Lucky bastard.

CONTENTS

PROLOGUE:

ONE:

TWO:

THREE:

FOUR:

FIVE:

SIX:

SEVEN:

EIGHT:

NINE:

TEN:

ELEVEN:

TWELVE:

THIRTEEN:

EPILOGUE:

PROLOGUE

A FOUR-DOLLAR TICKET

DURING THE SUMMER of 1973, with Watergate unfolding and Willie Mays redefining the phrase stick a fork in him, my father was wavering between a new motorcyle and a single season ticket for the Celtics. The IRS had just given him a significant income tax refund of either $200 (the figure Dad remembers) or $600 (the figure my mother remembers). They both agree on one thing: Mom threatened to leave him if he bought the motorcycle.

We were renting a modest apartment in Marlborough, Massachusetts, just twenty-five minutes from Boston, with my father putting himself through Suffolk Law School, teaching at an all-girls boarding school, and bartending at night. Although the tax refund would have paid some bills, for the first time my father wanted something for himself. His life sucked. He wanted the motorcycle. When Mom shot that idea down, he called the Celtics and learned that, for four dollars per game, he could purchase a