ALSO BY KEVIN COOK

Titanic Thompson: The Man Who Bet on Everything

Tommys Honor: The Story of Old Tom Morris and Young Tom Morris, Golfs Founding Father and Son

Driven: Teen Phenoms, Mad Parents, Swing Science, and the Future of Golf

Contents

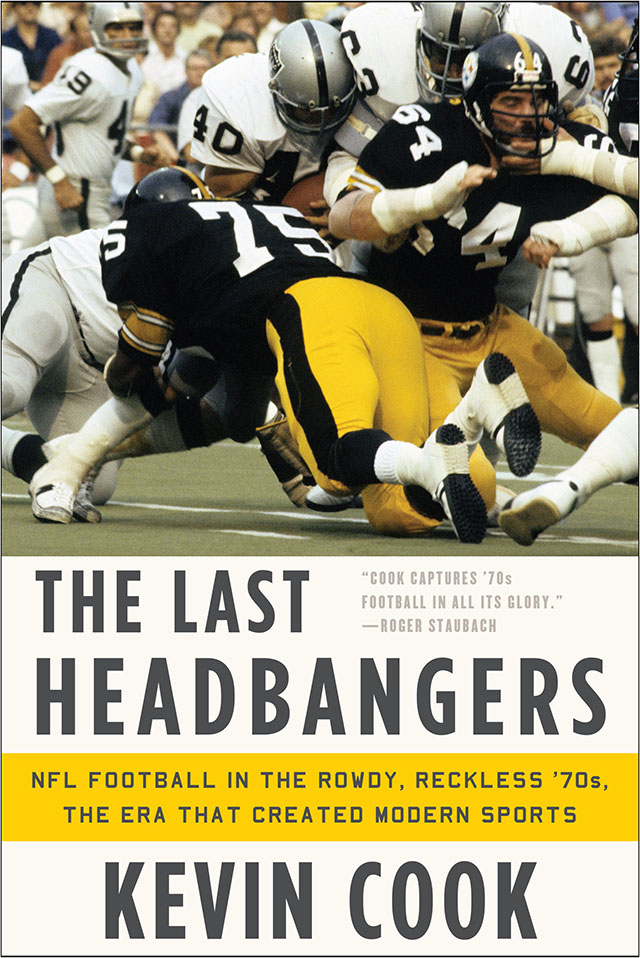

This book isnt meant to glorify the uglier aspects of NFL football in the 1970s and early 80s: the drugs, the booze, the cheating and head-hunting, the occasionally seamy sex, and the risks the game posed to players health. There may be no greater cruelty in modern sports than the toll pro football has taken on the bodies and brains of its players.

This book is meant to inform and entertain, but I also want to celebrate the courage of those men, who by the 1970s had an inkling of the risks and took them anyway. They played for their families, for money, for their teammates, for love of the game. The risks paid off for some of them and ruined others lives. Some went on to coach, while others analyzed the game on TV or found jobs that allowed them to shake hands and reminisce for a living. Others struggled with injuries that hobbled them or withered their brains to the point that they were senile at fifty. Others died before they turned fifty.

Was it worth it?

This book is dedicated to the players who took the risks.

Prologue

END OVER END

P hil Villapianos helmet didnt fit. The Oakland Raiders lantern-jawed linebacker stuck his head inside, gave the helmet a whack, and felt it rattle around his ears. Plastic piece of junk! Hows he supposed to stop Franco and Bradshaw with his helmet bobbing around on his head?

While Villapiano fussed with his helmet, other Raiders paced and fretted, stretching, cracking their necks and knuckles. The visitors locker room at Pittsburghs Three Rivers Stadium smelled of Brut and Right Guard and Hai Karate, liniment, and nervous sweat. The playersbig men but not giants, averaging six-two and 219 poundsadjusted their pads, guzzled water from squirt bottles, spat on the floor. Fred Biletnikoff, a scrawny receiver with thinning blond hair and a wispy mustache, stopped chain-smoking long enough to trudge to the can and loudly puke. His teammates mumbled what might have sounded like prayers in any other locker room, but not a room full of Raiders. The Raiders were pro footballs Hells Angels, and their mumbles were mostly curses. Safety George Atkinson stood in a corner, scratching the tight, shiny coils of his beard. Then Atkinson sprang forward, throwing a forearm shiver at a phantom opponent. Biletnikoff, returning from the can, sat on a wooden stool and tied the laces of his cleats. Tied and retied them. Ten times. Eleven times. They still didnt feel right. He retied them again, looking around to see if anybody was going to give him shit about it. No, the others were deep in their own routines, pounding each others pads, grinding their teeth, making their own toilet trips in the minutes before they took the field for their American Football Conference divisional playoff against the Pittsburgh Steelers. The Raiders were 4-point underdogs. Winner goes to the 1972 AFC title game, one step from the Super Bowl.

John Madden ran a beefy pink hand through his hair. Madden stood six-four, weighed 270, and sweated like the offensive tackle he used to be. His black polo shirt clung to an ample belly over polyester Sansabelt slacks. The youngest head coach in the league at thirty-six, he wasnt the rah-rah type. Madden had one rule: Show up on time and play hard on Sunday. He treated his players as professionals who didnt need pep talks. Pacing a locker room littered with socks and towels, Ace bandages, paper cups, and squirt bottles, studying his players faces, Madden thought his team looked ready.

Villapiano, for sure. As Madden watched, the linebacker yanked the silver helmet off his head. He took a breath, then reared back and smacked his forehead into the cement-block wall. Bam . Bam bam . Now he paused as if waiting for the wall to crumble. But that wasnt ithe was waiting for something else.

A moment later, Villapiano pulled his helmet back on. There, better. Knocking his forehead against the wall had made his head swell a little. Now the helmet fit.

A few yards away in the stadiums lower concourse, the Steelers sweated in their more spacious home locker room. They were less growly than the Raiders, more like a construction crew than a biker gang. Veterans Ray Mansfield and Andy Russell, who were among the better-paid Steelers, making $22,000 a year, carpooled to the stadium to save on gas that cost fifty-five cents a gallon. Quarterback Terry Bradshaw sold used cars during the off-season. Fullback Franco Harris, a rookie with Fred Astaire feet and the chiseled features of Hercules, sometimes hitchhiked to home games. Fans who lingered after the game might pull out of the parking lot to see Harris standing on the curb in jeans and a dusty jacket, flagging a ride home. Now Harris sat with his hands folded, staring at the green linoleum floor. A few feet away Roy Gerela, alone as usual, as a kicker was supposed to be, picked at the extralong sleeves of his jersey. Defensive end L. C. Greenwood stubbed out a pregame cigarette.

John Frenchy Fuqua picked his helmet off a hook beside his cubicle. Off the field, Fuqua sported a feathered Three Musketeers hat, a cape, and a gold cane. His favorite pair of platform shoes featured hard-plastic heels with live goldfish swimming around inside. Claiming to be a French count turned black by fallout from a nuclear test, he warned opponents that he would deliver the coop de grah on em. Steelers coach Chuck Noll, passing between players, nodded to Fuqua, who was checking his helmet for smudges and his uniform for lint, tapping his toes to some internal music. That was Frenchy, off in his own world.

Noll, forty, was even less rah-rah than Madden. On the first day of training camp hed told the Steelers, If I have to motivate you, Ill get rid of you. Noll and Madden were part of coachings younger generation, men who rejected the old-fashioned image of the NFL coach as a World War II general throwing fits and barking orders. They were more modern than that. They were space-age coaches who saw their jobs as similar to that of the lead engineer on a NASA mission: Manage your personnel, draw up a game plan, anticipate surprises, and create multiple responses to possible setbacks, including last-ditch options. When the game starts, let your men execute the mission.

Noll scanned the room. This was the time when old-school coaches delivered rousing pregame speeches.

Terry Bradshaw could have used a little rousing. The Steelers third-year quarterback was this crews gawky country boy, a Bible-reading Forrest Gump with a secret. Despite his rifle arm and aw-shucks manner, Bradshaw suffered moods as black as his helmet. He wanted approval, even love, from a coach who saw open emotion as a sign of weakness. (Later, when Marianne Noll ran to hug her husband after a Steelers Super Bowl victory, Noll shook her hand.) Alone with his worries, Bradshaw sat at his cubicle clenching and unclenching his throwing hand.

The coach cleared his throat. A few players looked up. Noll spoke without raising his voice, almost as if he were talking to himself.

Next page